1975

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #190. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Kcab ti nur.

———

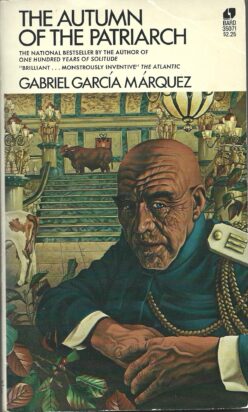

Welcome back to the Time Tour, this time we’re heading back to the ’70s and deep into the heart of power, and talking about Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Autumn of the Patriarch.

The first victim of Power is time, the story of the general with his long forgotten name has no full stops and the effect that creates is a dizzying one – when was the last time your head was grabbed and pushed so deep into someone else’s half-tangible past you forgot how to breathe? Would you remember what the smell was without it? How long before you forgot who the hand belonged to? How long before you forgot it was there at all? Maybe it’s something divine? Something eternal? The lecher’s scent now comes with a popping sound and some sulfur – a birthday, a funeral, a battle won, another medal on his lapel, I thought that was tomorrow, perhaps yesterday, a fortnight yet to be, when the cock crows…I haven’t heard him in so long – the first victim of power is time.

The second victim of Power is self, we never learn the name of the fading general – and it’s faded from his people also, this devil has no name, only hollow titles filled with spectral meaning, this devil general, this general devil, this bedeviled general, boogeyman who sees beyond sight, whose twitch of a finger removes a man’s head from shoulders, family from land, children from youth – there is no room for names in the putrid realm from which he draws his power, this is no story of heroes whose names are subject of songs forever, after all it is not the revolutionaries that cause his lonely and rotting death, this is a tale of absolute and overwhelming force, the kind that wriggles into reality itself, the second victim of Power is personhood.

The third victim of power is feeling. There are of course mountains of writing on how Gabriel Garcia Marquez uses magical elements to convey horrors that can’t be captured in plain speech. This novel varies on that theme, with touches of magic but largely relying on humor – with the greatest horrors of the work emerging from its comic highs. Specifically, a subplot with the most hilarious moment of heightened farce involving a rigged lottery spins into one of the novel’s darkest moments involved the massacre of hundreds to thousands of children. It is the blurring between the ridiculous and the grotesque that sustains the critique put forward in this novel. To portray an autocrat as a fundamentally serious being of cold logic and raw power is to buy into their propaganda. Only fools imbibe the rot and think themselves its master. The third victim of power is laughter.

There are few easy comforts or lessons to be found in this novel which has horrors from start to end – except for the knowledge that even those who cling to thrones must die eventually. I’d like to imagine a world where as soon as the news of the death of the dictator reached the masses, a paradise was built to dance on his grave eternally. However, the nature of the kind of power, the power of the dictator, of empires, of generals and their many medallions, has a way of managing to resurface. But maybe next time we’ll make sure they don’t get to end their reign in a decrepit peaceful sleep.

———

Oluwatayo Adewole is a writer, critic and performer coming to you live from the British and Irish Isles. You can find her roaming the streets on his bike or at https://tayowrites.persona.co/ if you’re at a more pedestrian pace.