Making Prince of Persia: A Family’s World War II Survival Memoir

This is a feature excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly #190. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Oftentimes, we internalize all kinds of messages from hearing our parents’ stories at the dinner table when we’re younger, like a record player on repeat, or beating the same levels of a videogame again and again. In Jordan Mechner’s case, he had internalized that no matter what he was going through in school at Yale or making critically acclaimed video games like Prince of Persia, Karateka and The Last Express, it would be nothing compared to what his family went through. His success would be the kind of success that a civilian could have in a time and place of peace. He wouldn’t unpack these feelings until he became an adult who could process these messages his family was telling him, and he’d go onto honor it through writing, researching and drawing his family’s story. Replay is a graphic memoir telling the story of Jordan Mechner and his family through four generations, through both World Wars, the history of game development and through his divorce.

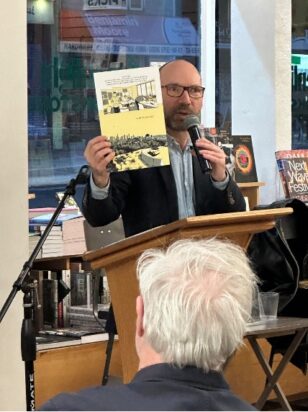

In a panel at Greenlight Books in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, Mechner discussed his developing the book extensively. Structurally, it’s told with events in chronological order, while also hopping between multiple timelines, using various images, themes and even places to connect from each scene to the next, almost like a game mechanic. Examples include two scenes using a snowy winter background being a visual bridge. Or Mechner actually going to visit the same train station in the present day that his father visited in the past.

Graphically, the multiple timelines are distinguished through multiple color palettes to represent the interweaving stories. The main storylines follow Jordan’s life as a game developer, and his father’s survival through World War II, escaping the Nazis. Secondarily, they also explore his grandfather’s story in World War I, and his partner and children with him in the present day. Mechner also painstakingly recreated scenes and tableaus that he took great lengths to research and draw himself. It was surprising to hear that he wasn’t an artist from a young age, but before he was a game dev, he had a passing interest in comics in his youth that he re-ignited as an adult and channeled his side interest into a professional one in his memoir. But it wasn’t just a fun exercise to tell the story that way, he also valued telling his life story as he personally remembered it. He said drawing the story himself was essential for telling the story he wanted it to be told – he couldn’t ask an artist to draw his relatives’ mannerisms on a chance encounter, or to allow a separate artist to depict people, places and objects the way he remembered them, or wished to personally visualize. Even if the jumping timelines do get a bit messy to follow at times towards the later parts of the book, on the whole, it succeeds at creating a faithfully researched, stirring, personal, multigenerational epic.

Mechner’s consciousness seemed shaped from a young age by his family’s choices in survival, like a choice-based narrative game. Replay tells his family’s survival story through the ages and the choices they faced, like characters in one of his games. He recounts facing his own choices too, such as whether or not he should have allowed his son to move to France for military school. His friend tells him “Life is not like a videogame that you can replay.” His grandfather in World War I faced survival in the horrors of trench warfare. And of course, there’s the many quandaries his father and his Grand Aunt Lisa faced to survive in Western Europe. Like other war stories from the period, they face disease, starvation and many close calls with the encroaching Nazis often in a virtually random fashion. When Mechner’s grandfather travels to Cuba early in the Nazi campaign in Western Europe, their separation should have lasted only a few days, but instead, the rapid closure of ports and means of travel resulted in a saga of survival and heartache.

Mechner does provide extensive behind the scenes of how he fact-checked his book on his website (lovingly crafted multimedia commentary which is definitely worthy of diving into on its own). But even as well documented and life altering as these memories can be, memory can be fickle. It would be a point noticed by his father, who not only provided a 1,000 page memoir of documentation (”that was like too much documentation!”), but is also a behavioral psychologist. One story involved Mechners’s father and aunt Lisa working in a tobacco shop in France, and befriending a Nazi pilot named Willi. Lisa made a judgment call to not explicitly reveal they were Jewish but also to find some humanity in each other, which he reciprocated. They didn’t blame him (“the war wasn’t his fault”). Later, friends of Willi’s, German soldiers, gave them a tip off that saved their lives. Even though the story served to be an unlikely parable about survival through making an unlikely ally, Mechner went to the town where the tobacco shop once existed, and he wasn’t able to corroborate the records of his father’s story. At Greenlight Books, Mechner seemed to trail off and the panel quickly moved on.

These generational memories have a way of living with Mechner’s family and in himself, in dramatic ways without us realizing, sometimes until later in our lives. Hanging over Mechner’s life is the idea that, no matter what he was going through now (working out designs for a hit game, moving his family to a different continent for a game studio, emptying his bank account on a project, marital issues) it couldn’t be as bad as what his family went through in the early to mid-20th century. Also, no matter how peaceful things seem now, things could always get worse, sometimes rapidly. The city of Vienna could be the peak of civilization, but toppled within a generation by World War I. Or all the heartache of their family’s deaths and harrowing survival in World War II could have been avoided by just leaving early, haunting Jordan’s father like a specter for decades.

Replay is a genre defying graphic memoir that acts not just as a celebration of game development, but as a warning. On one hand, it’s a game industry memoir about the triumphs and trials of one of the most successful game designers of all time belonging next to books like Doom Guy by John Romero or Reggie Fils-Aime’s Disrupting the Game. On the other hand, it’s a graphic survival memoir of his father from the Holocaust, belonging next to Art Spiegelman’s Maus or Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl. It defies a single category, and the lives of game devs and the people we know often defy single categories like that. In a post Gamergate, Trump world, it’s a reminder that within each game dev is a human being with lived histories of trauma, strife and survival. It’s a reflection on family, crisis, the haunting specter of authoritarianism and memory. It’s a memoir that reminds us that behind all people lies an intergenerational story waiting to be told, and many of those people happen to be nerds, programmers and game developers.

And as the future continues to unfold in a new era of rising authoritarianism and specters of war, some of those stories may have yet to be told.

And sometimes those stories can only be told after the fact, like a game being replayed, over and over.

———

Charles H. Huang (he/him) is a game programmer, game writer, narrative designer, and community organizer based in NYC. His work has been covered in Rock Paper Shotgun, PC Gamer, and Critical Distance. He has exhibited at Magfest, Narrascope, Play NYC, PixelPop Festival, LA Zine Fest, and Different Games. He ran Unparty at GDC and co-founded 501(c)3 nonprofit Friendship Garden, before receiving his MFA from NYU Game Center in 2021. He is a fan of Mr. Rogers, Jim Henson, and Hayao Miyazaki. Follow him on Bluesky and Instagram.