Procgen Revelation

This is a feature excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly #189. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

There’s a hole at the heart of detective games. It’s the space between all the things that can be said about a game, and all the expectant expressions from someone who really can’t tell you why, but this is their game of the year and you just have to play it please please please.

That empty part is, maybe inconveniently, the entire identity of the genre.

Speaking as someone who adores detective games like Return of the Obra Dinn, Her Story and The Case of the Golden Idol, we are really hard to talk to. But our aversion to spoilers doesn’t come from sheer vanity: The entire gameplay loop of a detective game is the discovery of new information. Revelation – the sudden thunderclap sensation that to fit this tiny piece of evidence into your mental model, you have to turn the whole thing on its head – is the detective game equivalent of floating brick pathways in a Mario game. Only, retracing these pathways is literally not possible, because playing means learning, and replaying means somehow forgetting and relearning.

By that same token, all detective games come with an expiration date. They are pulled into the gravity well at their center, leaving us to endlessly hunt for more. Or, failing that, drag our loved ones in after us with swirling, vague descriptions about the joys that await them at the center of the black hole.

Luckily, game developers have a solution to this problem: procedural generation. Canny designers pack their code with the necessary building blocks, and the computer compiles them in a way that’s never been seen before. A procgen detective game seems like the perfect morsel for such a wonder-hungry genre. Infinite surprise! Novelty from horizon to horizon! Unluckily, I’ve played that game. It didn’t work.

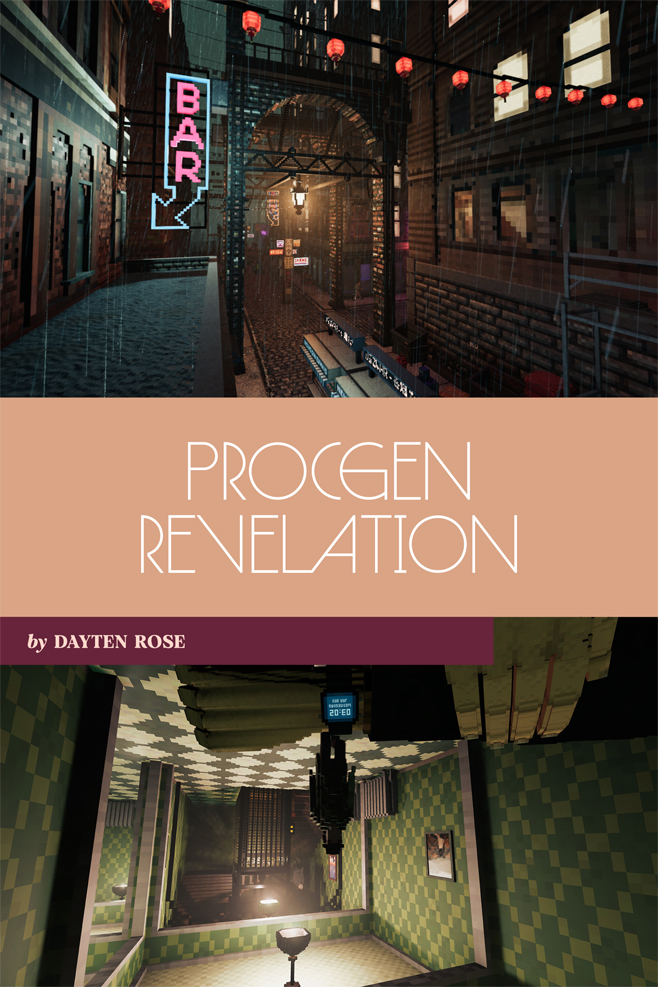

Shadows of Doubt is a bona fide procgen detective game set in a neo-noir metropolis populated by potential murderers and victims. For a down-on-their-luck private investigator, it’s a playground. For a fan of the Phoenix Wright games looking to escape the cycle of simply running out of things to play, it seemed like a fountain of youth – but it was a mirage. The clouds never parted, and revelation never dawned. Worse, it wasn’t even a misfire. Shadows of Doubt is a successful experiment with a negative result. It proves why the maw of detective games will never fully be satisfied.

A run of Shadows of Doubt kicks off with a police scanner breaking news of a nearby murder. I remember rushing to the scene of my first crime, a run-down apartment with its door wide open. Out front is a police officer standing guard. In this game, I’m an independent operator: more than welcome to do the police’s work for them, but not legally allowed to do so through the proper channels. I’m barred from entering, even though I can see the victim sprawled in their own front entryway.

After clanging around in the apartment’s ventilation system, I emerge into the victim’s unit. I creep behind the police officer and whip out my scanner. The scene is a mess of footprints of different sizes, and I catalog a few of them for my pinboard, ruling out those worn by the officer whose feet I surreptitiously scan.

Then, pandemonium. The victim’s roommate, apparently unbothered by the commotion, spots me while popping into their kitchen for, I guess, a midnight snack. They alert the guard, and I dash for the exit, but not before being ripped apart by a ceiling-mounted sentry turret. I reload my last save. Each subsequent attempt ends the same way.

I spend most of my time in Shadows of Doubt crawling through buggy ducts, stumbling into brawls in random apartment kitchens, and imagining complexity in the faceless bracken of citizenry, any one of whom would be equally likely to draw blood if the simulation commanded them to. I’ve never even solved a case. The most noir thought I’ve had the entire time is, “I should take up smoking.” Instead of feeling smart, I feel powerless.

It wasn’t the ballistic-fingerprinted, silver bullet I imagined it would be. But to Michael Cook, a scholar of procedural generation at King’s College London, and the founder of PROCJAM, Shadows of Doubt is an ambitious experiment. For all of its flaws, it’s the grandest example of a game in its specific genre – which is, crucially, not the detective genre.

Besides the fact that you literally play as a detective, the misattribution of Shadows of Doubt may stem from the fact that it belongs to the same generic category as detective games: information games, defined by designer Tom Francis as games where “the goal is to acquire information, and also the way you do it is to use information you’ve already gained.” Cook himself has made two games exploring the intersection between information games and procgen. Nothing Beside Remains and Condition Unknown stick the player in the aftermath of, respectively, an abandoned village and a monster attack at an arctic research base.

Using written records and environmental clues, it’s possible to unravel the events that transpired there, but it’s not mandatory. Both games are more about the process of exploring the simulation than proving how smart you are. Both games leave you to your own interpretation. In a paper with Florence Smith Nicholls, Cook calls this kind of game “generative archaeology.” As the player, you’re emerging after the simulation has already run its course. And if procedural generation is meant to evoke the chaotic mashing together of natural laws in the real world, then exploring the simulation in this way is indeed a kind of reconstruction of the past.

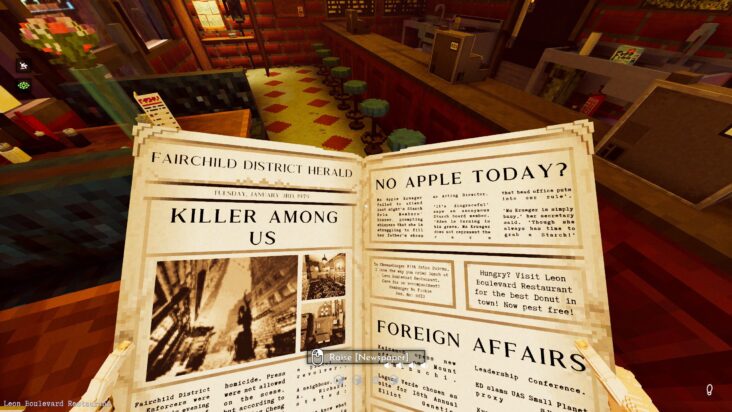

Shadows of Doubt is also a generative archaeology game, but in real time. Its procgen engine doesn’t generate mystery plots on purpose. It simply cooks its simulation so that murder becomes inevitable. If you’re at the right place at the right time, you can literally catch your killer in the act before the police scanner even dings. That adds another layer to the footprints, fingerprints and shell casings that get left behind: they are not narrative conceits in a mystery story, but physical residue of the criminal act itself.

This approach to investigation requires the player to preside over chaos. You’re never presenting a bit of crucial evidence at trial that turns the whole case on its head or realizing, with a dawning sense of dread, that the plucky witness who’s been helping you along is actually a cold-blooded killer. To give an example: In one job, I had to locate a random citizen. I knew their workplace, so using a city database, I pulled up the employee register and spent the next half hour cross-referencing every individual profile against other randomized identifying information (blood type and build). It was slow, tedious and close to what I imagine actual crime fighting looks like. Shadows of Doubt is a detective job sim, but not a detective game in the way we typically use the term, which is closer to a detective novel or TV show.

———

Dayten Rose is a Kansas City-based writer covering puzzle and detective games. Follow them on Bluesky.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 189.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!