A Fistful of Westerns

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #195. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Interfacing in the millennium.

———

2025 was the year of the Western, for me. I watched a lot of them! I have always liked westerns, by which I mean I grew up playing Red Dead Redemption and Fallout: New Vegas, but until recently I wouldn’t say I knew anything about them. Then, last January, I was trapped in an unfurnished apartment sans Wi-Fi with a 30-movie Western collection and a dream, and somehow I never lost interest. I spent most of last year, when faced with a few hours to myself, thinking, Damn, I want to watch a Western. In much the same manner as the time I read Lonesome Dove to stick it to the old men at my work and then ended up becoming a diehard Larry McMurtry evangelist, it turns out something I was doing semi-ironically for shits and giggles became an incorrigible brainworm that made my personality worse for an extended period of time. These things happen. The point is, Westerns are interesting.

American Western movies are inextricable from their context: born from westward expansion and the violence of colonial land acquisition, it then became a self-perpetuating myth about American individualism, the sanctity of the family unit and about self-sufficiency and righteous isolation. As the genre progressed, those myths turned inward and cannibalized themselves, or took on the tone of parody, as exemplified by the cynicism of later Spaghetti Westerns and their rejection of moralism in favor of money. But it’s not like you can classify a whole genre as politically good or politically bad. Big-name American Westerns like High Noon or The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance are obvious political analogies that have been studied to death, but I found smaller players in the genre have just as much to say.

Take Barquero, for instance, the 1970 Lee van Cleef/Warren Oates vehicle about a barge operator stuck between settlers and bandits, whose control of the river crossing turns into an almost mythical war between him, the bandit chief and the hopes and dreams of the men on both sides. In Barquero, the setting itself interrupts the traditional Western structure – instead of an open landscape, the location of the river town makes the environment claustrophobic, as everyone submits to the funnel of the barge in order to make their crossing. Warren Oates’ bandit chief is therefore not just warring with Lee van Cleef’s barge captain over the barge itself, but about their access to the promise of the West, to that expanse that they desire to loot and explore. The figure of the captain is not a traditional Western hero attempting to steer the moral direction of his community but instead almost a representation of the West itself: apolitical, inhuman, and the ultimate judge of both the greed of the bandits on one side of the river and the expansionism of the settlers on the other.

Or maybe let’s try Howard Hawks’ El Dorado, the awkward younger sibling of Rio Bravo despite being a better movie in basically every respect. El Dorado follows the same plot but with a level of engagement and emotional depth absent from Rio Bravo, whose main goal as a film was to oppose the alleged communist sentiments of High Noon, which depicted a sheriff abandoned by his community in an hour of desperate need. Instead of Rio Bravo‘s shallow “the sheriff does have help” storyline, El Dorado expands the premise to allow for a more convincing dynamic between its two leads while also, perhaps accidentally, stumbling into some extremely interesting territory with regards to addiction, disability and male worthiness. Robert Mitchum’s character is a sweating, stumbling alcoholic who’s treated with frankness and fondness by John Wayne, who acquires an injury early in the film that ends up partially paralyzing him, losing the use of his gun hand. Instead of Rio Bravo‘s leading man with a slavering supporting cast, El Dorado takes usefulness out of the equation: both Wayne and Mitchum’s characters struggle with physical capability, but this doesn’t lead to the pity of the narrative or to designate them as weaker characters to be protected, but instead drives them closer together, as they hold each other up – often literally – in their quest to take down a corrupt rancher.

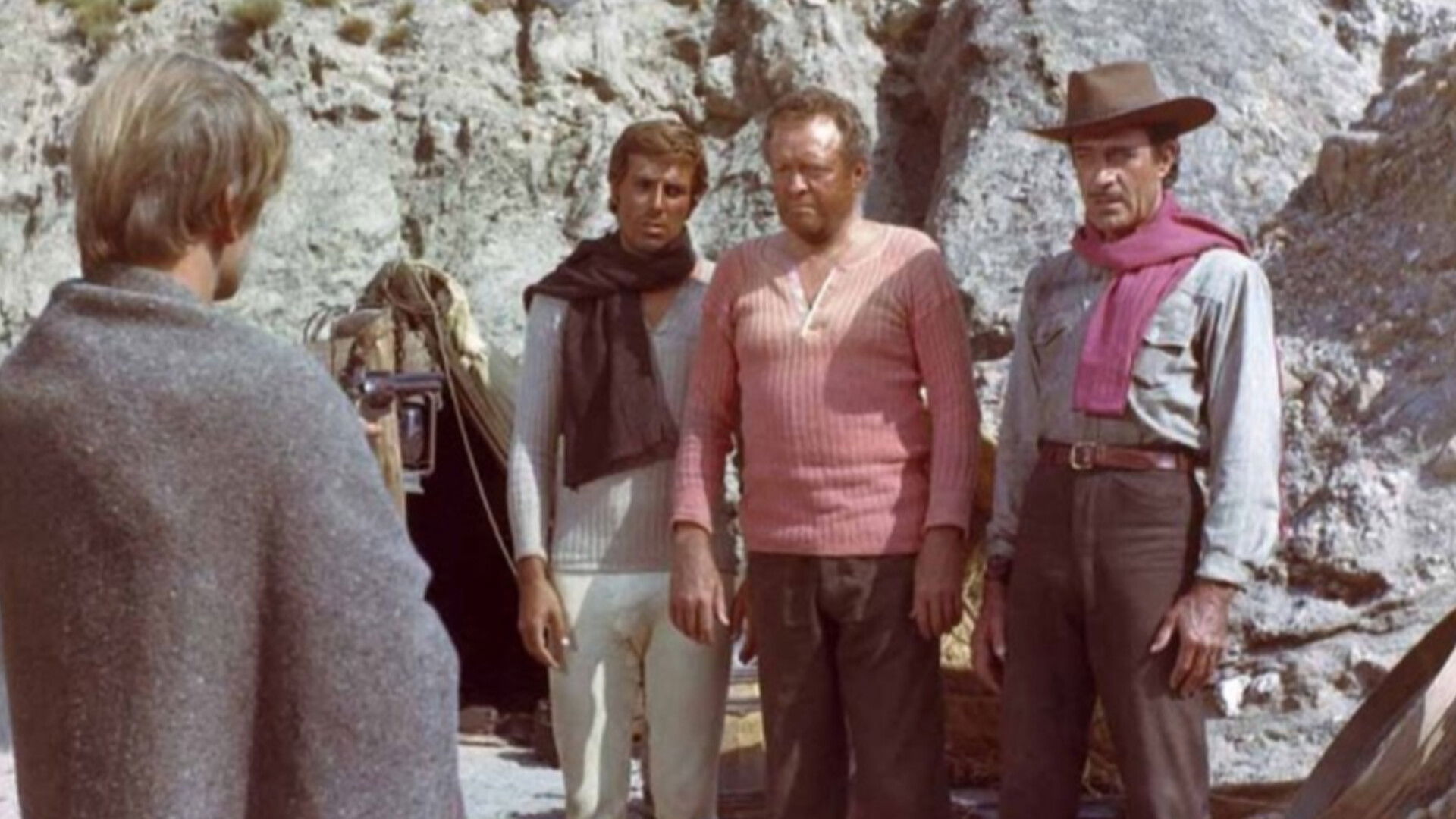

If we cross overseas, I found a great deal to explore in Giorgio Capitani’s The Ruthless Four, which on its face is just Van Heflin does The Treasure of the Sierra Madre with a homoerotic twist. In true Spaghetti fashion, it’s less about morals than about gold, but it gives another layer of depth to Bogie’s descent into madness from the original by adding rich, layered relationship to the four men that make it to the mine: Van Heflin’s aging treasure hunter, George Hilton as his cheerful but suspicious pseudo-son, Klaus Kinski as Hilton’s controlling, sadistic shadow and Gilbert Roland as Heflin’s old friend and last-minute recruit to balance out the dynamics of power, who still holds him responsible for a betrayal years earlier. Because of such intimate relationships between the four, the lust for gold becomes secondary, and the treasure itself serves primarily to inflame the affections and suspicions between the men as they ping-pong between trust of each other, lingering wounds, secrets and confessions and the desire not to die alone. It’s got plenty of Spaghetti Western cynicism and love of violence, but it also recognizes correctly that even in the brutal, murderous West there will be love between men and depths of feeling that can provoke events with far more conviction than just the hunt for treasure or the desire for power.

My main takeaway from my 2025 expedition, aside from the fact that there’s nothing as satisfying as a well-framed shot of a horse running fast, is that there’s basically unlimited avenues to play around within a genre. I’ve always had the idea that genre is constricting and that the best works of art are ones that are hard to categorize, but I don’t think that’s actually true. I’m learning to love the familiarity of genre tropes because it makes it that much more impactful when they’re subverted. I spent this year delighted to find things that had been done before, to watch a slightly different iteration on an established trope and to track evolutions and divergences. Uniqueness is overrated. Any conversation worth having has been had before and will be had again. They put Lee van Cleef on a horse for thirty years because they knew good things would happen when they put Lee van Cleef on a horse. And I have decided, bravely, that I will continue to watch Westerns.

———

Maddi Chilton is an internet artifact from St. Louis, Missouri. Follow her on Bluesky.