Andor (Again)

This is a reprint of the TV essay from Issue #94 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

This is a reprint of the TV essay from Issue #94 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

———

When I read Van Dennis on Andor (Exploits 92), I almost cried. In these times, I felt a righteous joy in the argument that the Empire treats its most loyal soldiers as disposable cogs, whereas the Rebellion “is a cause built on valuing everyone who’s a part of it.”

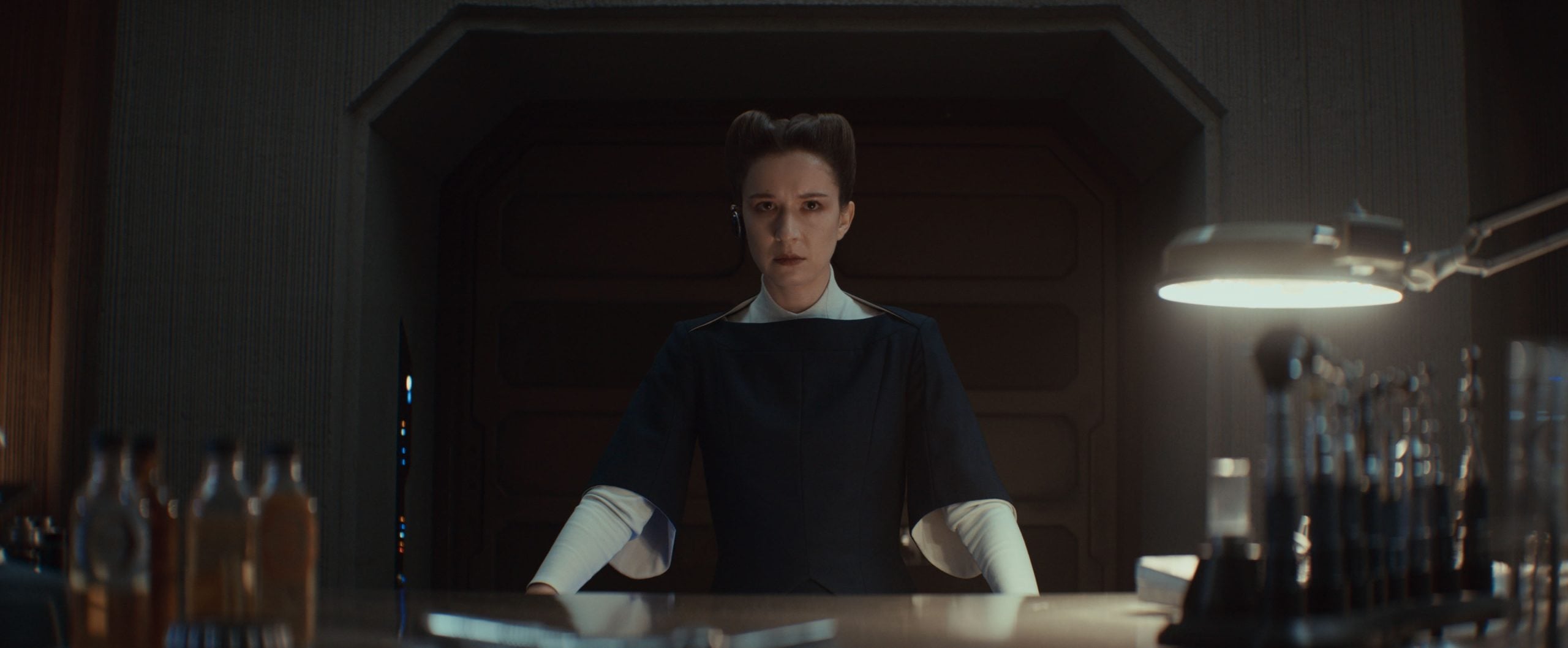

And then I remembered this exchange between Luthen Rael and the young girl he’s rescued:

Kleya: “Am I your daughter now?”

Luthen: “When it’s useful.”

I totally agree with Dennis on the Imperial urge to disposability: it is perhaps the most satisfying irony that Andor ends with loyal-but-suspected traitor Dedra in a prison like Cassian had been in. As if to say: the gears of imperial justice only have one setting for its enemies.

The Empire treats people like tools and we might want to tell ourselves that the Rebellion is different. And yet – Am I your daughter now? When it’s useful.

Luthen may be an outlier – “I’m condemned to use the tools of my enemy to defeat them” – but he could be the poster boy for instrumentalizing people: Anto Kreegyr (allowed to walk into a trap); Tay Kolma (a once-helpful banker who now drinks too much); the planet Ghorman (“It will burn… brightly”); (father and husband) Lonni Jung (left to be discovered by a pet tooka, like the cold opening to Law & Order: Star Wars Victims Unit).

And Luthen isn’t the only one using people for the cause. Remember Mon Mothma picking a fight with her husband for gambling just so her spying driver could report on that as the cause of some money problems?

Even for the Rebellion, people can be tools.

But I think if we stop here, we end up missing a crucial difference between the Empire using people up and forgetting them, and the Rebellion’s commitment to memory.

Think here of Luthen (“I share my dreams with ghosts”); of Vel admonishing an accidental killer (“You’re taking her with you”); of Cassian to Kleya about keeping faith with the mission (“You’re keeping Luthen alive”); of Mon Mothma reminding us of the Bothans who died.

Or think of Maarva, of her pre-recorded funeral speech, where she describes the joy of being turned into a funerary stone, of being both remembered and useful. And so, when her funeral turns into an anti-imperial riot, Maarva finds a sort of apotheosis: her funeral brick turns into a weapon, a tool working towards the act of bringing her memory into the present, the future.

Or put another way – the Empire says, “You have always lived like this,” whereas the Rebellion says, “I remember (the dead, the past, our dreams of a better world).”