In The End, It Always Comes Back to the Old House

This is a feature story from Unwinnable Monthly #192. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

It’s always going to end in a house fire. It did once before. There’s no way to separate the memories of the old house from the memories of its destruction, and every other little indignity that occurred within.

I was four years old when my father allowed me to sit on his lap and watch him playing Doom II: Hell on Earth on his Windows 98 computer, the one we had that was never connected to the internet, and it was a few short months before I was sitting in the too-large computer chair, cushions beneath me so I could see the monitor, clumsily fighting demons before I knew what there was anything symbolic to them.

Since then, it’s been a constant in my life, amidst the strife and motion that comes with growing up. I know it and its world and its rules like the back of my hand. I think that’s why the various tricks of myhouse.wad (technically .pk3) are as disconcerting to me as they are.

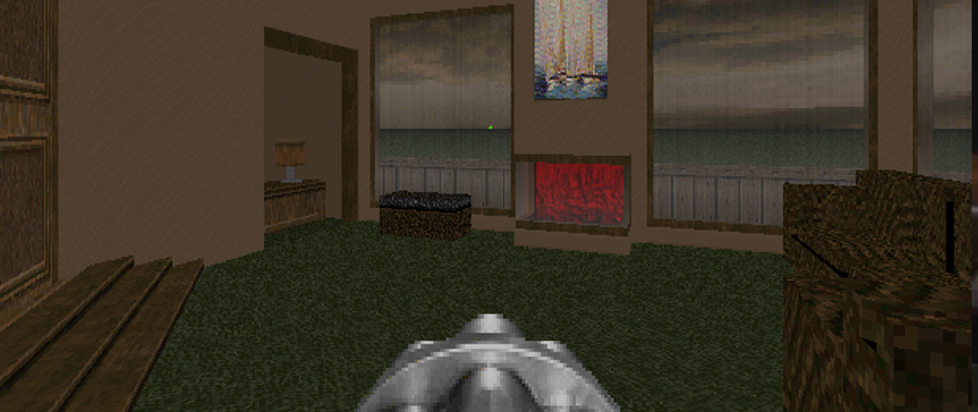

Released in 2023 via a post by user Veddge to the Doomworld forums, myhouse.wad characterizes itself as an old-school representation of someone’s childhood home, ostensibly touched up in honor of a deceased friend. It only presents itself like that for a short amount of time. Beyond some small rule-breaking tech, like the presence of a two-floored house in an engine that cannot layer planes atop one another, it appears to be a kitschy, if clunky simulacrum of a man’s nostalgia.

Then the doors vanish. The player is sent deeper into a house that begins to defy its own spacial limitations. The music begins to transform and distort. The animations become a bit too smooth for their own good. The only way out, for a first-time player, is to inadvertently trigger a house fire that modernizes the game far beyond what can be normally expected for Doom II.

I’d be remiss if I did not mention the overt similarities and allusions to Danielewski’s seminal postmodern horror House of Leaves. It would be an insult to suggest that these details are merely an homage to that book.

It’s always going to end with everything falling to pieces, isn’t it?

The scariest thing about growing up is realizing that sometimes old wounds never fully heal. They fester, they form scar tissue, but they crack under pressure. Even sealed over, they itch so terribly you scratch them open without realizing. Our memories are not set in stone; they are fluid and susceptible to dreamlike distortion and the ever-present smell of fire.

Myhouse is on its own a frightening work; it is particularly effective if you have a deeper knowledge of the Doom engine’s inner workings, its limitations, its trickery; it is frightening merely on its own merit as a non-Euclidean fever dream that parasitizes the game we are supposed to be playing. I love it for this alone.

The thing that elevates it into my favorite horror game out there is the way it so closely resembles my own unpacking of grief.

Visiting myhouse.wad always starts with nostalgia, either the personal or the impersonal – making similarly juvenile levels or either playing through them or filtering them out. But the unease just beneath the surface is always present. Oddities are written off as quirks or mistakes of perception. At last, though, when we get the blue key that offers us an escape, our attention is drawn to explore just a bit more. Then the rules change, and the only way out is through. You cannot leave the memory without facing the dissolution. Reality breaks down. It all becomes symbolic, incoherent, actively hostile to the warmth once felt in reminiscence.

No matter how far we wander, though, we always come back to that house, in the same way that in my restless dreams, I too revert to the embrace of my childhood home.

Only by breaking the rules, and entering the bowels of those old memories without regressing into the safe-terror of the house fire, can we start to move beyond that singular, terrible cycle of the past.

At the center of my connection with myhouse.wad is the minor incorporation of FEX’s “Subways of Your Mind,” a song that was at the time of release known as “The Most Mysterious Song.” Both the band who produced it and the title were lost in the shuffle. The only thing that kept it from being a hoax was that the radio frequencies confirmed it was played on a radio station in West Berlin, back in 1984.

At the time, though, the song existed in a quantum state of memory – known as much for the mystery as the music. In that way, in the same way that myhouse does, that song pulls us back into one specific temporal moment in time, forever lost, only replicable in the distorted, emotion-drowned way that comes with half-processed memory. Doom II’s Refueling Base always, for some reason, takes me back to a sunny afternoon in 2005, surrounded by the smell of my father and the half-formed feeling that things are going to be okay.

This saturates the meta-narrative within the Google Drive of Veddge – the developer constantly notes that the scale and nature of his level is ballooning and warping without his awareness. His attempt at a simple memorial for a lost hometown friend is perverted by hands that both are and aren’t his. Our intrepid creator begins to become afraid of his own memory of the house, because it shifts alongside the level.

In House of Leaves, the titular house is supernatural by origin, cosmic, perhaps even divine. Myhouse.wad, in contrast, is wholly a piece of human art. The intimacy of experience makes the horror far more obvious, far more relatable. My relationship with the Dark Souls trilogy, for example, has been permanently altered by its connection to a friend who is no longer present: “when you are held by the dead,” says Yasunari Kawabata in Thousand Cranes, “you begin to feel that you aren’t in this world yourself.” Grief comes with a pervasive liminality – a state of being both well and infirmed by the weight of longing – it is only when manifested through otherwise familiar experiences that this fact becomes tangible.

Art is at least in part spawned by one’s experiences – and it is disturbingly easy to lose control over a memory. Suddenly, when I go back, my memories of Doom II are interspersed with mourning a self I had never known, or waiting for the call that my grandmother had finally passed away after days of ceaseless fighting. These kernels were always there, always embedded – but I could not see them until a decade gave me clarity.

It doesn’t have to end in a house fire – but what terrifies me is knowing that for a long, long time in the aftermath, remembering is going to drive you to that broken electrical box behind the bookshelf. Distance only helps so much. Getting on a plane and moving on will not save the mind from flashing back to the shell of what that house used to represent. Escaping from the cycle requires unpacking so much more – the revelation that the fire, the destruction of the memory, is a safer option than grieving, is safer than the betrayal that comes with moving on and moving forward – for real this time.

I find myself hoping that, inasmuch as Myhouse.wad’s narrative is real, that Veddge found a way to unpack their grief in so many forms through this impossible art piece. I cannot claim to know if such a thing is even possible. I certainly have not found any sort of fearless clarity in my own creative works.

The wad’s “true” ending comes with a climactic battle in a gas station parking lot, a reclamation of Doom II’s chaotic innocence, a hint that the level might be cleansed of the horror that otherwise infests it with enough time, patience and enough cycles to complete the circle before it is too late. The distant sunset on the beach in the aftermath, filled only with the sound of the waves, suggests that peace is possible – but it will nevertheless be terrifying to get there. I’m trying, so is Veddge, so is every person who has resonated with the brokenness of the old house as represented within the depths of the mind.

Miss you, Thomas.

———

J.M. Henson is a freelance critic/author who haunts the Blue Ridge Mountains and is in turn haunted by most things out of their control. Follow on Bluesky.