Nightmare Logic and the Horrors of Confusion

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #191. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

We are what we’re afraid of.

———

I have to cop to something here. Even though I have faithfully produced a column here for what feels close to time immemorial, I have not actually played a horror game in… a hot minute. To be entirely clear, I haven’t played many games at all, so it’s not that my love for the spooky stuff has at all waned – my day job has been even more time-consuming than normal, and I simply have not frequently had the spoons for gaming in my free time. So, as I return here to write this monthly missive, my well of ideas has begun to runneth dry. This is, necessarily, a little stressful, especially in combination with the already-pretty-stressful-and-so-can’t-game day job. And when I get stressed, my dreams get weird.

Over the last month, my dreams have had many basic premises. Perhaps I am suddenly told that, for some reason, I have to fly to South Africa, and when I arrive at the airport, my gate keeps shifting spots in a never-ending terminal maze. Or maybe I’ve bought a new home, and when I arrive, I find that there has been some terrible clerical error and what I’ve actually purchased is an operational theme park, and I spend the dream wandering through an increasingly frantic carnival trying to find a manager to speak to.

A lot of these hijinks sound downright Muppet-esque, and in the warm light of conscious reality, they are pretty goofy. But in the moment of the dream, when I firmly believe that this is actually happening, I’m terrified. Not because I’m being chased by monsters or anything, but just because I have no goddamn idea what is going on. My understanding of external reality – that they must assign flights to gates that are real, that pickup basketball would be an extremely undignified decision-making tool – is turned entirely on its head. I don’t understand anything, but I am born inexorably forward on the current of this new bizarro world, and I am scared.

Now, onto the videogame thing. Games actually don’t traffic in the particular terror of Kafka-esque absurdity very often. This is likely because, in a limited procedural system bounded in space and time by lines of binary code, it’s actually pretty hard to create an authentic air of surrealism. Being able to break down things like ARG, hit points, etc, seems to lock most games into a certain stability, even as they play around with probability and stakes in some way. One of the few examples of games that can cultivate this sense of nightmare logic is the Silent Hill franchise, which appears so frequently in this column that I think I need to give Team Silent a percentage of my earnings. The way Silent Hill does this is not through any sort of mechanical manipulation during play, but through scripted interactions with characters and how your cumulative playtime adds up to one of several discreet endings.

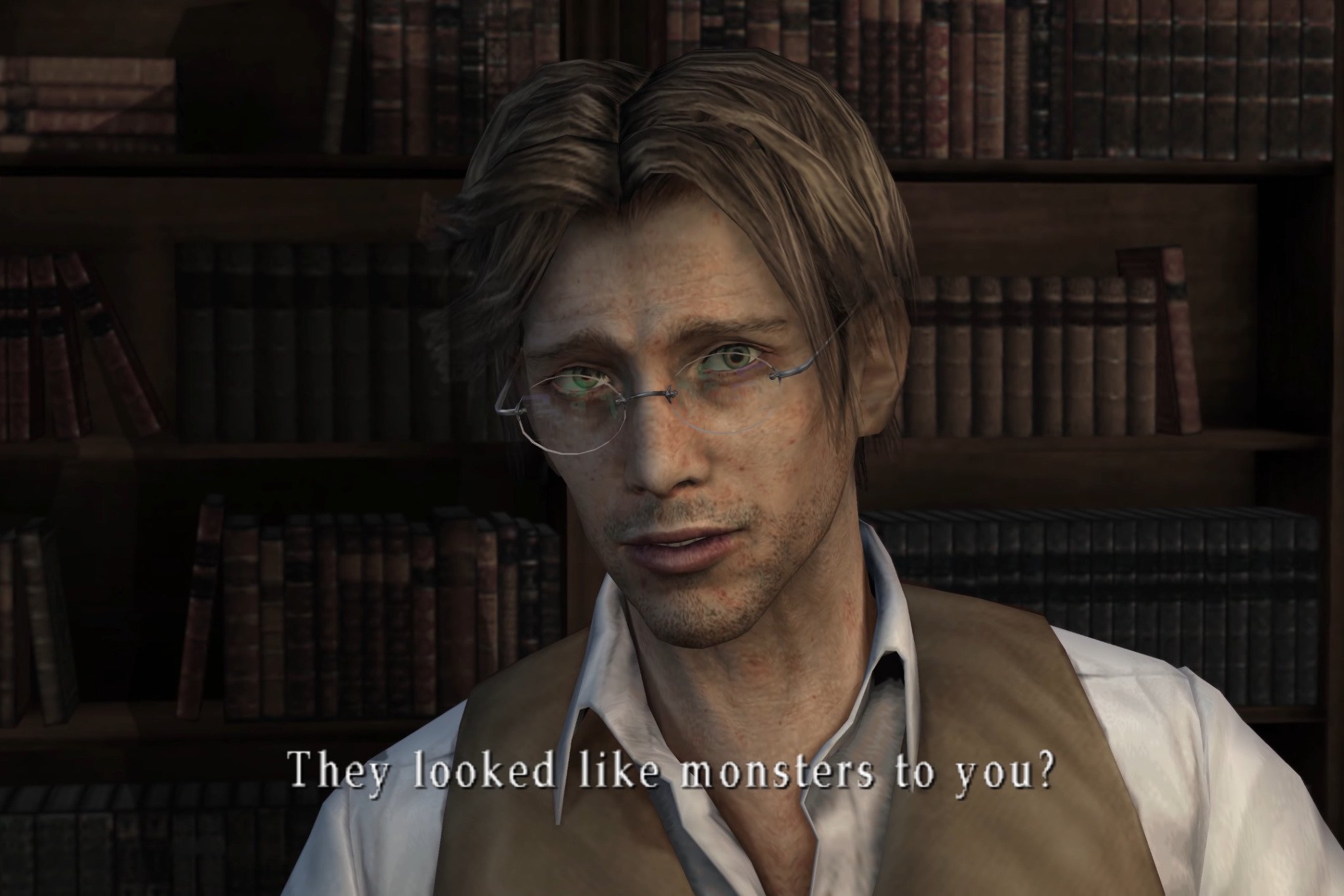

One of the key narrative throughlines of Silent Hill is that the landscape and entities moving through the town look unique to each person who finds themselves there. This is perhaps most famously meme-ified through Vincent’s questioning line in Silent Hill 3, “They look like monsters to you?” This line, delivered after the protagonist Heather has described encountering and killing countless monsters without understanding what’s going on, forces the player to reckon with the fact that, while we see what Heather sees, there is no actual guarantee that the monsters in front of us are “real” within the game world. They might just be people, or nothing at all. There’s a solid chance that Vincent was simply trying to manipulate Heather here, but this is not the only example of Silent Hill changing to fit the neuroses/trauma/grief of particular inhabitants. The poignant final encounter between James and Angela in Silent Hill 2 comes to mind: James finds Angela seated on a staircase that is engulfed in flames. He comments that it’s extremely hot in the room, and she asks him if he can see the flames now, too. “For me, it’s always like this,” she intones, before ascending the stairs. The idea that each person trapped in Silent Hill is seeing their own unique version of Hell, and only occasionally do those visions overlap, means that at no point can your character effectively communicate with anyone else, which leads to a lot of the disjointed, dream-like dialogue.

Similarly, the ending you receive (because I hesitate to say “earn”) at the end of several of the games is tied not to a lot of conscious moral decision making a la Bioware, but to seemingly innocuous choices (do you exit through the door with the rust-colored egg embedded in it, or the scarlet egg?) or things that you weren’t aware were choices at all. In the Bloober Team remake of Silent Hill 2, the ending you receive is impacted by how many enemies you kill (as opposed to avoid or flee from) and how long over the game you left James at less than half health. Things that are undeniably important to the game, but that can seem more or less a function of inventory management instead of conscious choices. Maybe he was at half-health because you ran out of items. This can give the ending a sense of being unearned – you had no idea what choice you were making, and sometimes you couldn’t do the thing the game wanted. But all of this, ultimately, folds back into the idea that Silent Hill (game and town) simply does not make sense and trying to wrangle control over your time there is futile.

And what could be scarier than that?

———

Emma Kostopolus loves all things that go bump in the night. When not playing scary games, you can find her in the kitchen, scientifically perfecting the recipe for fudge brownies. She has an Instagram where she logs the food and art she makes, along with her many cats.