Money Makes Kaso-Machi Go Round

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #190. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Interfacing in the millennium.

———

At the risk of beating a dead horse, I’m going to have to bring up cozy games again. The discourse around the topic has been cyclical and annoying but I think, to get a brief overview of the arguments and counterarguments, the best reads are the 2018 Project Horseshoe report on the design of cozy games and the 2024 response/exploration Comfortably Numb: An Ideological Analysis of Coziness in Videogames.

Some bullet points from the 2018 report, which is a good summary of what coziness is and the general assumptions around it:

- It defines coziness as “how strongly a game evokes the fantasy of safety, abundance and softness”

- It argues that cozy games “help [the] player practice fulfilling higher order needs”

- It explores the ideas of “cozy aesthetics” and “cozy mechanics,” among other design aspects

- It summarizes its thesis as “Coziness is a subversively humanizing design practice in a society built on monetizing base animal needs”

And from the 2024 response, which is a more specific critique of coziness’ relationship to capitalism:

- It argues that cozy games “do not challenge the capitalist status quo, but rather act as an ideological pressure relief valve for life under capitalism”

- It focuses on the specific link between coziness and consumerism by defining coziness as “an atmosphere originating from material assemblages of objects possessing specific tactile and sensorial qualities”

- It finds that “cozy atmospheres reproduce ideologies of class, status and consumerism,” explaining that they can be “both a coping mechanism and a reproducer of ideology”

These are the two sides, insofar as there are two sides: cozy games are a radical rejection of capitalist society vs. cozy games are an unintentional replication of capitalist society. (I am simplifying, obviously. This is a dense and complicated debate. There are arguments across the whole spectrum of thing good versus thing bad. I digress.) The most important thing to take from this is that the question of the relationship between cozy games and capitalism is 1) interesting and 2) unresolved.

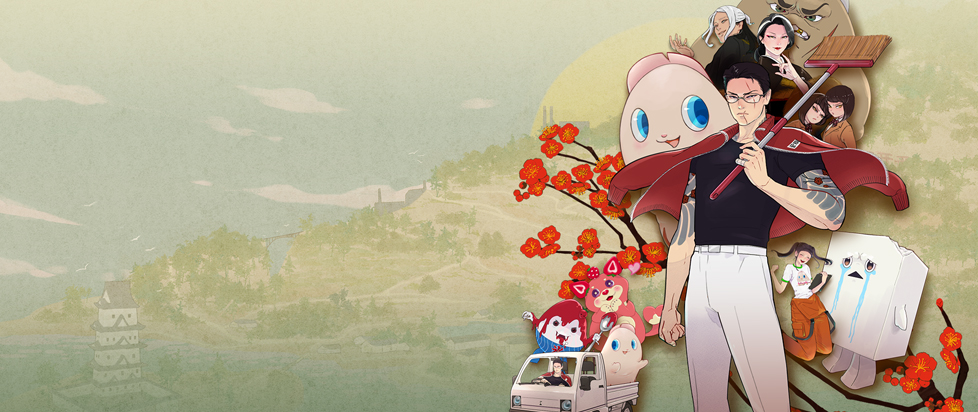

I found myself coming back to this conversation over and over when I reviewed Promise Mascot Agency earlier this year. Promise Mascot Agency, in many ways, is the bizarro-world version of one of these cozy games. It borrows the structure of a gentle, heartwarming community-building game and sets it in a miserable, dying little town full of garbage bags, tacky billboards and broke, bored, neurotic freaks who are just as likely to be aggressively horny as they are to be actively weeping. More than that, though, Promise Mascot Agency seems to have approached the question of how do cozy games deal with capitalism? by just steering full speed ahead into the capitalism bit. It is by the absurd nature of the game itself, of Kaizen Game Works’ house style, and of the wholehearted embrace of their bizarre premise that this works.

The management sim elements of Promise Mascot Agency do not actually require much management. The structure of the game, of mascot and job acquisition, and of the narrative pacing is such that Michi will almost inevitably find himself in the red until the moment he finds himself swimming in money. There’s not much strategy or granular detail involved at all. Instead, what the management sim elements of Promise Mascot Agency serve to do is to submerge both Michi and the player in the inescapable environment of his role as a guy who must make money. The moment-to-moment actions to send a mascot out on a job are as rote as can be, but they’re also constant and unavoidable. Michi’s current bank balance is displayed prominently on the UI, as are the agency’s fame level, available jobs, in progress jobs, Matriarch Shimazu’s debt and any mascots that need assistance. The structure of the management aspects of the game is constant interruption. There is no way to focus on the calm parts of the game – chatting with villagers, hunting for collectibles, bopping around in your little kei truck – without the persistent visual and mechanical distraction of your business and debt.

In this way, Promise Mascot Agency does seem to add another argument to the #discourse about coziness, capitalism, consumerism and cute things. It chose to ignore the oft-litigated aspects of games it shares a core structure with – the romanticization of pastoral life, the commodification of cozy aesthetics, the refusal to admit that working in a coffee shop fucking sucks – and instead throws itself headfirst into the parts of small business no one likes talking about. Time off. Bonuses. Revenue share. Burnout. Bee attacks. Employees being needy. The coffee machine breaking. Normal sized doors. Utility bills. Franchising. Merchandizing. Debt, debt, debt. Then it does this for the setting, too: you want to rejuvenate a dying village by crafting, building and decorating? You want to make things look charming and personal while also being creative? Sike. You’re doing bureaucracy. You’re going to a room in the basement of city hall. You’re personally responsible for investing money if you want to see literally anything get done. When all else fails you get involved in a complicated legal case that’s come down from the big city because at the end of the day that’s politics. This is what fixes the world. It’s never that pretty.

It genuinely does seem like the developers of Promise Mascot Agency took specific pains to un-cozy their game. It shares an extremely common structure with many games in that subgenre: you move to a small town to revive a local business, pull the community together, assemble a group of quirky comrades and eventually learn a heartwarming lesson about the value of friendship. It then takes every opportunity possible to reject the aesthetic and mechanical hallmarks of said genre and instead teaches that heartwarming lesson about the value of friendship to a bunch of weird, violent freaks and perverts while bashing you over the head with overwhelming numbers and invasive pop-ups. This is what is really interesting about Promise Mascot Agency: it also shares a strong thematic similarity with many cozy games. It is about community. It is about family. It is about people (and mascots) trying to help each other and come together across differences. It is about the damaging effects of capitalism, greed, environmental neglect, political ambivalence and personal nihilism. It offers (in my personal opinion) an ultimately comforting, hopeful view of the world.

But it doesn’t attempt to make playing it actually comforting. Playing Promise Mascot Agency is a chaotic, atonal, overstimulating and often confusing experience, and it’s like that on purpose. It divorces the moral from the mechanical and aesthetic, where discussion of cozy games so often conflates the two (I won’t get into the implications of wholesome games, but this is where I would get into the implications of wholesome games). It is a comedic exaggeration of the constant lament of the genre, that all those sweet little stories feel interrupted by a gameplay loop of urban development or buying things or making money. It interrupts intentionally. It leans into its discomfort, annoyance and nastiness. It wraps up its hope in a tacky little package and tells you to sit there until you’ve finished your food. It doesn’t avoid the question.

———

Maddi Chilton is an internet artifact from St. Louis, Missouri. Follow her on Bluesky.