Plumbing the Depths

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #189. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Architecture and games.

———

I’m sure you’ve noticed that I’ve been spending a lot of time playing The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom. I have a certain tendency towards completionism, feeling somehow compelled to finish every quest, pick up every collectible and unlock every line of dialog in my games. This can sometimes be exhausting when it comes to massive open worlds like what you’ll find in Tears of the Kingdom, to be completely honest. This would mostly be on me as opposed to Nintendo, but when push comes to shove, they make the games, I just play them.

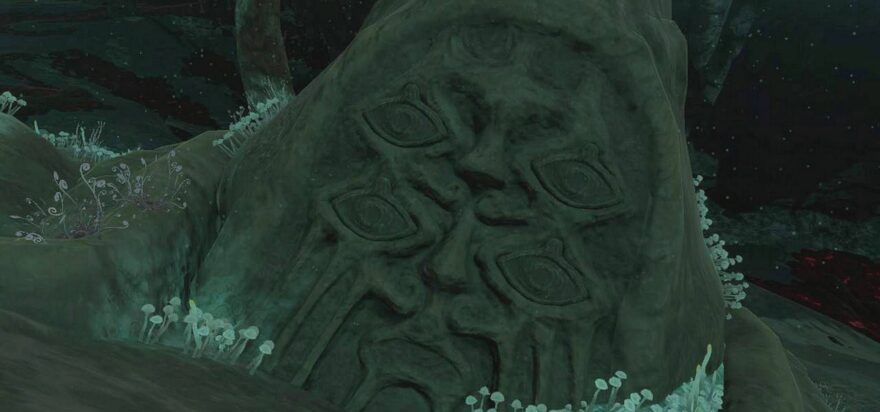

Hyrule in Tears of the Kingdom stretches across the familiar surface world but also extends into the skies above, while plunging into a subterranean expanse below, something never before seen in the series, at least not really. When it comes to open world games, I always take a systematic approach to exploration, so as you might expect, I finished everything on the surface world prior to venturing into the skies, and I’ve only just begun my plumbing of the depths.

What you need to know before descending into the deepest, darkest depths of Hyrule would have to be that you’re dealing with a kind of shadow world, a place that mimics the land above, but quite simply in reverse. I found this incredibly frustrating. The mountains above equate to a chasm below and every shrine is mirrored by a lightroot. This could only have been intentional, drawing on ancient concepts of mirrored worlds or inverted geographies, at least in so far as I’m ready to assume. In my experience as an archaeologist, having spent almost a decade of my life digging holes in Egypt, I can only see the most vivid parallel in this particular case being the Egyptian understanding of the afterlife, where the soul travels through a structured but mirrored underworld, a place known as the Duat.

In the mythology of ancient Egypt, the Duat wasn’t just a concept, it was considered to be a physical realm with clear geography. The underworld consisted of rivers, gates, fields, walls and as you’d likely guess, various types of housing, basically tombs. Descriptions of the Duat appear in funerary texts including the Book of the Dead and the Book of Gates, each detailing how the soul could be expected to pass through the Duat over the course of twelve hours, in other words the night. This journey through the Duat was dangerous but necessary, filled with protectors, aggressors, defenders and attackers, along with tunnels, corridors and passages which tested the worthiness of the deceased. The ultimate goal was rebirth, a passage back into the overworld, ideally back into your own body, previously preserved.

In so far as we terrestrial creatures are concerned, the surface world in Tears of the Kingdom offers a familiar but grounded experience, while the depths provide a glimpse into the unknown, unconscious and of course uncovered spaces buried below. These are hostile but rich with opportunity. Plunging into them isn’t a singular event. This would be a necessity. The game design encourages constant movement between all three levels or planes, mirroring the Egyptian concept of the soul, known as the Ba, which had to move about the whole of the physical realm, in order to achieve completion, becoming an Akh. You’re not really supposed to finish each one in separate succession like me.

In terms of their topography, the depths are something like a photographic negative representing the surface. Mountains become depressions. Rivers become ridges. The famous shrines align perfectly with underground lightroots, meaning that when you discover one, the other is revealed. This mirroring isn’t incidental but invites you to navigate using a kind of cartographic memory, recognizing familiar forms distorted by inversion. The technique emphasizes a spatial and symbolic duality long recognized in Egyptian mythology where the world of the living and the world of the dead are understood to be reflections of each other, spaces which are intimately connected.

The underworld was typically associated with the direction of the setting sun, with tombs being carved into the cliffsides, facing the underworld. These tombs, particularly those in the Valley of the Kings, were in fact architectural simulations of the Duat, filled with painted corridors, inscriptions of celestial boats and even star maps. The architecture of the dead for the ancient Egyptians mirrored the cosmic journey which occurred after nightfall. When people passed away, they didn’t just lose consciousness, they started a journey through space and time, finding themselves in a state of constant and perpetual transition.

When it comes to Hyrule, the depths function as a landscape of purpose. Regardless of their apparent ruin, they’re a place with structure, featuring lost mines, abandoned camps and forgotten forges, remnants of a previous civilization which appears to have existed as much underground as on the surface. Rather than a chaotic maze of devastated buildings, the depths in Tears of the Kingdom are part of a layered history, much like the Duat. You’ll have to face your fears while confronting challenges, being required to overcome adversity or be destroyed in the process, annihilated by monsters or defeated by gloom.

Tears of the Kingdom doesn’t just rely on vertical movement, being focused on layers of experience or perhaps existence, more pertinently stated. The journey of the sun god involved Ra traveling from the world of the living into the world of the dead, each day completing a cosmic cycle. Souls for the ancient Egyptians followed a similar trajectory. The different levels or planes of the game world in Tears of the Kingdom offer unique resources, and you’d be more than remiss to avoid or ignore any of them. In much the same way, the cosmology of ancient Egypt required the soul to move between realms in order to achieve balance and renewal, ultimately rebirth in some other form.

The underworld was not a realm of death in the final sense but a place of continuous transformation where the strength of souls could be tested, histories could be left buried and renewal, perhaps even redemption, could ultimately begin. When it comes to understanding the world in which we live, you first have to understand its shadow, then you can emerge renewed.

Suffering is a part of life that we try to avoid, occasionally despite ourselves, often on purpose, frequently to a fault. I can only say from experience that it’s mostly a fear of the unknown, and there’s more comfort in hardship than ease, reflecting the journey of the soul in the mythology of ancient Egypt. This cultural knowledge may in fact be representing the journey of ordinary human experience, as opposed to a literal afterlife.

———

Justin Reeve is an archaeologist specializing in architecture, urbanism and spatial theory, but he can frequently be found writing about videogames, too.