The Listeners Draws a Line at Naziism

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #189. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Elsewhere, here.

———

I have a theory* that magic, in fiction, is the expression of the hurt we feel in this world by way of an impossibility that highlights our want through its presence. The Listeners, the new novel from Maggie Stiefvater, has a theory that luxury does the same thing. Luxury is a kind of magic and those who create it for others are magicians. And just like any other kind of magic, its presence creates an absence for those without it. “True needs, wants fears and hopes hid not in the words that were said, but in the ones that weren’t, and all these formed the core of luxury.” The wealthy do not need help procuring luxurious items, that’s just wealth. Luxury – the book reminds me over and over – is the assurance from a designer that you’ve purchased the right item, it’s the item showing up in a lovely box before you realize you need it, it is, maybe, not needing the item at all. “Nimble. In a drought, it was a glass of water; in a flood, a dry place to stand.” Not a thing, but a process of obfuscation; a mirage fairy-world that the wealthy are pulled into and leave not quite recognizing the world around them as it is.

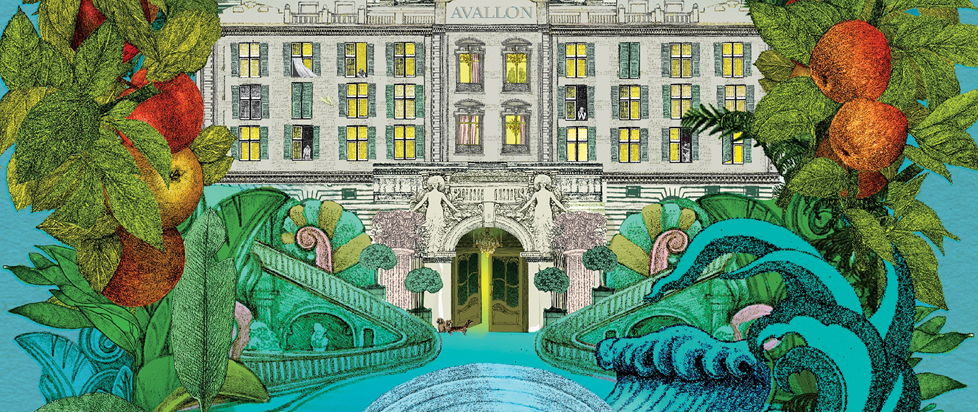

The Listeners is a story about an interesting time in US history that I was not aware of before I read the book, in which several high-end hotels were taken over by the United States during the Second World War for the purpose of hosting Axis diplomats and other POWs until a transfer agreement could be reached. June Hudson, the general manager of the Avallon (the fictional hotel of the novel) is disgusted by the thought of bestowing the same luxury to enemy nationals as they do to their usual guests, and dismayed on behalf of her Jewish and Black employees, and the ones that have family away at war, and the ones who are soon to be drafted. But she has no choice, and she reminds herself that: “The perfect guest was not necessarily the perfect human. […] The hotel wasn’t for those who deserved it. It was for those who came.” The novel is curious about complicity: that of the various German and Japanese nationals luxuriously imprisoned, but also of the wealthy. The hotel cannot function as a moral arbiter of who deserves to be taken care of, but where is the line, and what is the cost?

Politicians in the contemporary United States, having seemingly abdicated the idea that the Government can and should care for its constituents, is asking similar questions of voters. How many Nazis are you willing to put up to maintain your wealth? If you are comfortable, how much of their agenda are you willing to ignore? It’s magical thinking that Trump will put money in anyone’s pockets but the very wealthy, but the illusion persists and many will feed women and queer people and people of color to their local demi-god if the beast demands it. Not only Trump voters; many mainstream Democrats have made it clear that they will also promote the Naziism of anti-Trans legislation, of anti-immigration racism, without even a gesture of remorse.

The Avallon offers real magic to its guests, the impossible kind, not just the illusion of it. The hot springs that run under, around and through the hotel take the pain away, heal, soothe body and soul. June, who grew up poor with a strong West Virginia mountain accent, becomes the GM of the Avallon not only because she is great at the job, but because she can hear the water’s unspoken desires in the same way that she can for her guests. The pain leeched into the water stays there, though the joy does too. When Jane can keep the hotel happy the water stays in balance, but if it begins to turn, she must become the sin-eater, giving the water her happiness and taking its dismay. It is worth it, for a long time, because running the hotel makes June happy. Taking care of her guests and her staff makes her happy enough to refill her tank after she drains it to sweeten the water, and they model other, less extractive, models of care for her. She knows there is nothing romantic about poverty. She knows that her guests aren’t perfect people, but neither are her staff, and she still believes that they deserve employment, safety and dignity. Where is the line, and what is the cost?

The Listeners is a sensitive, empathetic novel that isn’t interested in the eat-the-rich fantasies that have become popular in genre fiction in the last couple of years (not a bad trend), but however sympathetic it does not abandon a strong liberal moral core that says you cannot accommodate Nazis without tainting any good you try to accomplish. The water, ultimately, cannot handle the sourness of a couple that will willingly take their autistic-coded daughter back to Germany where they know she will be sterilized. It cannot handle that as much as this couple tries to protect their daughter – specifically – they have not wavered in their overall support for Nazi ideology. One ought to hold the line at Naziism, the novel suggests. There can be no healing until we do.

*It’s a thesis, it’s the thesis of my dissertation, it’s a little more than what I’m writing here but it’s also exactly the same.

———

Natasha Ochshorn is a PhD Candidate in English at CUNY, writing on fantasy texts and environmental grief. She’s lived in Brooklyn her whole life and makes music as Bunny Petite. Follow her on Instagram and Bluesky.