Toxic Waste from the Stage to the Page: The Witchland Trilogy

The art of adaptation is a fickle beast. How do you retain the soul of something as it was intended while translating it to a completely different medium? It’s a question even the highest budget studios have grappled with, but it can also arise from the indie sector, like with the comics in my virtual hands today: The Witchland trilogy. These three graphic novels are based on a trio of stage plays of the same name, all written by Tim Mulligan, who, with the artist Pyrink, adapted them all into graphic novels published by Highpoint Lit.

The stories center on the family of two gay men and their adopted black daughter as they navigate the twisted town of Richland, plagued by all manner of supernatural horrors. If you recognize that name, it’s because Richland is based on a real place where Mulligan lived. As he explains on his website, the themes of addiction and improper handling of toxic waste are inspired by what he saw during his years in Eastern Washington, dubbed “the most toxic place in the Western Hemisphere,” in Newsweek.

As we touched on with Who Killed Sarah Shaw, toxicity of all kinds in the American heartland can lead to a great story. The addition of supernatural elements on top of the real horrors of nuclear waste has a lot of potential, like Chernobyl meets Silent Hill. I was sent all three volumes digitally for review, so I’ll be talking about them chronologically, with as minimal spoilers as possible. All images were provided by the project’s creator Tim Mulligan.

Witchland

The first volume starts with a great premise revealed over time. A nuclear power plant goes rancid in the 1950s, and at the same time, a kind young woman interested in becoming a missionary ends up instead a twisted witch by the hands of a wicked cult. All the seeds are planted for a unique blend of nuclear disaster and occult horror. Yet for all the ambition and interesting ideas, the final execution of the first volume leaves a lot to be desired.

There’s no getting around it – this story doesn’t feel adapted so much as almost taken verbatim from a play script into graphic novel form. And as I said, adaptation is hard, that’s understandable, but comics have benefits a stage play doesn’t. In turn, there are things that might work for a stage play, like lots of character dialogue, that can actively get in the way of the visual storytelling of a comic.

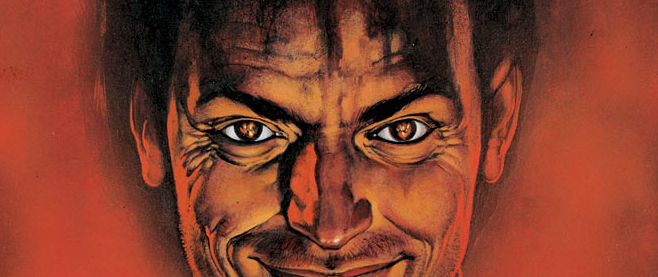

Firstly, and most unfortunately is that Pyrink’s art can vary substantially in quality across the first volume. Moments of haunting can be great and spooky! The color choices are especially great. Yet, the family’s daughter, Ali, can sometimes appear as though she’s bouncing from eighteen to thirty depending on how her face is drawn, even within the same page. Her fathers, Jared and Van can be all over the place with their expressions, at times looking out of sync emotionally with the scene. It’s not consistent, and the dips can be jarring while reading. Hand proportions also look a bit off in a few panels.

Pyrink’s style is rather unconventional. The eyes and mouths tend to be exaggerated, yet the heads and bodies are more subdued with more muted King of the Hill-esque shapes. All the while, there’s some lovely realistic shading, and some painterly texture work. It’s a distinctive mix, but it also can lead to odd moments when the elements clash.

Pyrink’s strength lies in mood and atmosphere. He comes across as an artist better suited to something with limited dialogue to worry about, and that’s the opposite of too much of Witchland. It’s when the witch comes out that Pyrink starts to have fun with things. Unfortunately, the script seems intent on focusing on the same few characters, talking in the same handful of rooms, adjacent to the same one street. If the family’s house were haunted, or if the climax centered around the witch’s house, I could understand this. Instead it’s fairly mundane conversations intermixed with pivoting back to the horror story.

The story itself isn’t bad on paper, but it is unrefined. There’s a lot of superfluous dialogue and a struggle for focus. The theme of addiction shown through Van’s drinking problem is admirable but it’s not really relevant to the horror. It’s tragic to see him relapse as things get worse, yet there’s not much conveyed other than we should feel frustration and pity. Typically a topic like that would be the focal point of the scares, rather than just sort of lingering in the background like a loose video cable. Instead, it’s Jared directly haunted by the witch and involved in the toxic waste management, and Ali who is functionally the protagonist. She’s the one who solves everything, and is correct to the point it feels a bit too easy.

I would be so down for a new woman of color crime solver in the horror space, but she’s just not that defined as a character. It’s fair that Mulligan, as a white man, isn’t going to understand all the nuances of being a teenage black girl, but there’s resources to consult for that. What’s more, the entire family has hints given in dialogue to discomfort from the surrounding, predominantly straight/white suburbia, but it never really amounts to anything? In fact, Ali near-instantly befriends a local white girl (and her boyfriend) that’s currently being haunted by the witch. Shannon and Brett even become lifelong friends of the family, recurring throughout the rest of the series.

Other than familial drama, the only pressure comes from Judith, the witch. She’s creepy, that’s for sure, but her power level varies considerably. She goes from a made-for-TV movie level threat to Freddy Krueger-tier demon in the blink of an eye, only to have her role concluded in a very anticlimactic fashion. The nuclear plant’s role in things is fairly disconnected as well, only really having payoff in the sequels.

I can see the vision of a suburban The Shining, but it’s not realized. This needed a firmer guiding hand of an editor to realize its fullest potential. The ending tries to pull a twist, but then the subsequent volume immediately retcons what precisely happened. I’m actually grateful for that though, because credit is due to the creative team for pivoting towards where their interests more clearly rest. It’s to the point that Judith is written out of the story in one word bubble. I am curious what the original plan was, but given how progressively better the sequels get, I’m inclined to believe this course correction was the right call.

Snitchland

The second volume, Snitchland, is the most serious entry. It’s simultaneously the least scary, though the protagonists mess with some less than advisable means of speaking with the dead. At the very least, the ghosts are much better woven into the central premise, even if mostly used to convey exposition amid a slowburn conspiracy.

The new additions to the cast are welcome, everyone returning is better drawn, and the panel work in general is a notable improvement. Pyrink clearly upped his game, even if his linework can still sometimes be rougher than ideal. That’s mostly because it makes the new 3D rendered elements of the locations contrast a tad more than seemingly intended, but the increase in locations is deeply appreciated all the same. However, Pyrink’s strong use of color and framing is still his best flex. The transparency of the ghosts is well executed.

As for Mulligan’s script, it’s a noble goal wrapped up in a less than ideal sandwich. Snitchland trades its predecessor’s repetitive scene framing, rougher visuals, and lack of focus for glacial pacing and monologues. There’s a dedicated story beat devoted solely to a very sad yet equally dry meeting of the aggrieved families and former workers of the scheming corporation responsible for the failed nuclear facility and subsequent waste clean-up. Mulligan goes so far as to frame someone speaking from the pulpit at church and at a podium in an events meeting hall as parallels.

I can see how this might work better for a stage play, with the energy of a performance to carry things, but even then… it can get long in the tooth. The stakes are supposed to be heightened from the threat of tangible corporate spies, yet it’s hard to feel that urgency. If anything, the story becomes so grounded that the moments that ghosts do things can feel out of place.

It begs the question of why even make it a story about ghosts who can influence the physical so vividly if they’re going to do little for the majority of the pages? Maybe that’s the metaphor? Our own forgotten agency. Except if a good metaphor makes your story harder to read, you have to weigh if that’s worth it. It’s frustrating because the opening to Snitchland is great, with an emotionally moving funeral bookended with a solid hook teasing a small-town conspiracy. Then it just wallows in its talking points. Arguably Van is more in the lead this time, but it’s not a particularly exciting story to lead in.

Where the first volume struggles for a clear message, the second is so focused on it that entertainment is sacrificed for the sake of the message. Regardless, if nothing else, it sets the stage for when the series finally starts to come together with the climactic third volume, even foreshadowing it with a Marvel-style epilogue scene that is then retold in the full third volume.

Twitchland

Twitchland is where you can see prior lessons learned. The compositions and panels are far more dynamically arranged and framed. The word bubbles are reasonably sized. The art style truly comes together. Pyrink’s grasp of expressions takes its greatest leap yet. The new threat finally merges both supernatural and nuclear-waste based elements together into a tangible, radioactive vampiric ghoul-fueled addiction wave.

However, understand that this volume is by far the campiest premise for the trilogy, with a decidedly lighter tone after last time. I would not be shocked if some just leap to the third volume, even if some internal references will be confusing for those who skipped ahead – not enough to make it ill-advised. This isn’t to say the volume is flawless, but enough comes together here that the points to grapple with are meatier than the nuances of adaptation.

In addition to its broader improvements, Twitchland circles back to themes of addiction with the much clearer throughline of vampirism. That said, I do worry whether the vampiric addiction being spread by bats rather than systemic failures of society trivializes the inherent problems that lead to drug addiction. Fentanyl is briefly brought up as a problem but then has nothing to do with the plot. The nerdy vampire lord responsible for it all is an effective villain purely in the camp horror sense, but I’m not sure how recovering addicts will feel about the narrative framing.

More subjectively, the overt referencing of the titles of all three graphic novels in conversation was a bit on the nose. And Mulligan really upped the pop culture references to almost Whedon-esque levels. References and in-jokes are totally fine, but you don’t want them to distract from a scene.

What irks me the most though is that this late into the trilogy, Ali’s ability to always be right is merely addressed as her being “a genius.” Why does this irk me? Because this was a huge missed opportunity. The first volume was Jared’s trial. The second was Van’s. The third should be Ali’s. With her now in college, this could’ve been a story about how the experience is changing her. Instead, the story sees her spending a break trying to help Brett through his character growth.

So just to be clear, the woman of color who has suffered trials, loss, and tribulations has to set everything aside to help the token straight white character? Why isn’t this a story about how the high performing daughter that everyone expects to be perfect finally can’t keep up and makes the mistake of abusing substances before seeking help on the cusp of burning out? It’s a premise so worth exploring, sitting right there, giftwrapped, but instead it’s a story about Brett, the least interesting cast member.

At first I thought maybe Van would instead be more of a leading man again. He survived addiction twice. The others sometimes lean on his ability to identify that something’s up, but that’s about it. So then Van is just the local potato-based donut baker with sassy one-liners, except when following his daughter’s lead. It’s still better told overall than the prior two volumes, and it’s nice to see characters carry over from the prior volumes, but the heart still isn’t beating a steady rhythm.

What is the metaphor of Brett’s addiction being caused by toxic bats biting him? What does that add to the story? If anything, making him the focal point just sees him be an obstacle for the sake of being obstinate. Don’t get me wrong, an addict can be defensive and avoidant about their problem, but there’s nothing presented here about such struggles to help someone that are particularly insightful. Most of the other addicts are just random unlucky people attacked by the drug dealer vampire’s pets. It lacks the necessary grounding to cohesively communicate an effective allegory.

It’s the same issue with the final tease during the epilogue. Because it leaves the story open to another tale, but… I don’t understand if the twist is some final conclusive narrative flourish. And if it is, what is it saying? Is it just subversion for the sake of subverting expectations?

There has been an improvement on the assembly, the stick shift works as intended, and the seats are all properly secured, but this car still needs some engine work if it wants to travel. And it could. I would not have spent so much time ruminating on something that I didn’t think had untapped potential.

There is still a good idea here, and the groundwork is solid enough that I hope that Mulligan and Pyrink revisit in the future. I just also can’t pretend that this series will be an easy sell to the average comic reader. This is specifically for those who appreciate potential over final execution.

———

Elijah Beahm is an author for Lost in Cult that Unwinnable graciously lets ramble about progressive religion and obscure media. When not consulting on indie games, he can be found on BlueSky and YouTube. He is still waiting for Dead Space 4.