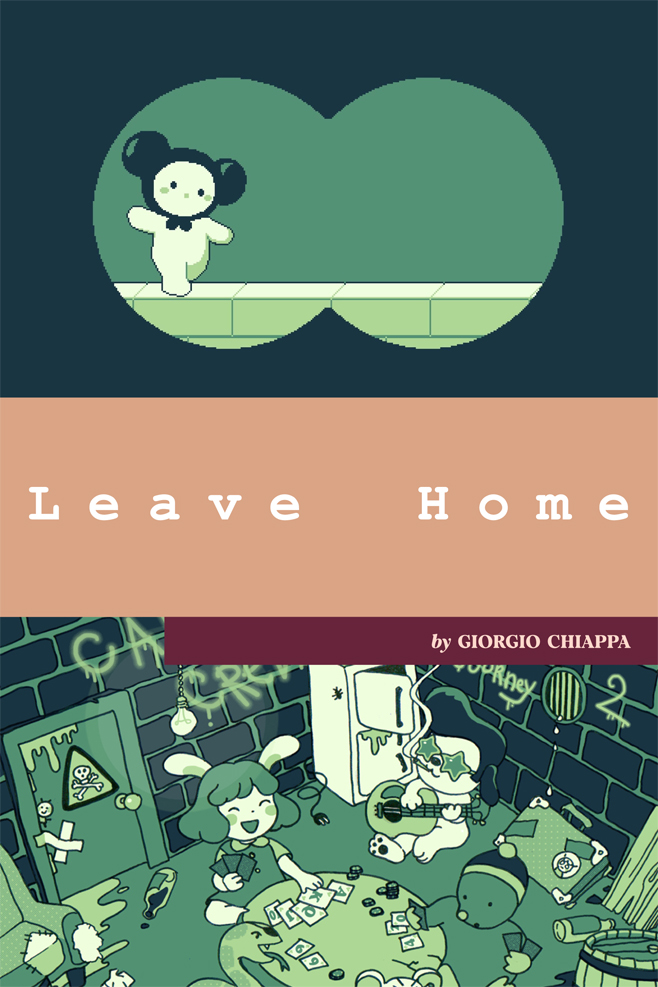

Leave Home

This is a feature excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly #189. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

This is the street where your friends live – all Victorian semis, greenery and open sky, an unencumbered horizon that stretches towards the city hall. And these are the homes where you were kindly invited, with their upstairs and downstairs, and enough room for the whole family, each member with their allotted portion of space to conduct a small life of their own. These are the potted plants, these are the doilies, these are the stairs.

And these are the city hall, the concert square, the cafés and the kiosks, with punters hanging out on balconies. The life of the neighborhood neatly fits into the mold dictated by its container – the affluent suburban street. It never runs out of joint; it is safe and predictable, except when an outside force crawls out of the city’s crevices to disturb its peace.

And these are the flats in the citizen wing of the factory. This is the computer room where you work. These are your colleagues and neighbors. And this is your bed, in your room, on your floor, in the factory where you work.

This is the minimart with its parking lot, an interzone between your friends’ part of town and the rest of it. This is where the likes of you keep quarters. This is the edge of town.

Going out to the dirty boulevard

In Indie narrative game Melon Journey: Bittersweet Memories (Froach Club, 2023), class divides in the protagonist’s hometown are something so ordinary to the characters that they are hardly ever a topic of discussion. They do not need to be spelled out in conversation, because the game enacts them in the spaces around the player. We play as Honeydew, a young anthropomorphic bunny and office worker who is doubly bound to her employer – Eglantine Industries – for offering her both a place of work and a place to stay, since she inhabits a dingy little room in the company’s building. Another wage slave sharing her living situation is her friend Cantaloupe, who goes missing at the beginning of the game, thus kickstarting Honeydew’s quest to find him.

We find out quickly that Honeydew seems to have friends in the safer, squeaky clean, wealthier part of Hog Town, despite not living there herself. The first experience we have of these suburban avenues is a feeling of breeziness, cleanliness and openness which stands in sharp contrast to our meagre factory life, not to mention the run-down mess that is the Eastern part of Hog Town – where you never get to gaze upward, and remain fixed in an isometric perspective, most of the screen occupied by cement, metal-sheet roofs, dirt. The improvised skate park where your hoodlum antagonists (a motley gang of misfits who torment your wealthy friends) hang out is cordoned off by a grate, beyond which we only see pitch black. There is a threat of repression looming in the air – we quickly find out that the police have little hesitation snatching up people from this side of Hog Town with little provocation. As the unwitting hyphen between two realities of our hometown, we as Honeydew will have the chance to tug at the threads of the town, to see its sewers and beaches, its backyards and secret passages. A privilege we hardly ever get for our own hometown(s) in the real world.

This Must Be the Place I’ve Waited Years to Leave

Whereas Honeydew never seems to have left her hometown, Mae (a zoomorphic cat) from Night in the Woods (Infinite Fall / Secret Lab 2017) revisits her native Possum Springs after dropping out of college, with an attitude that is halfway between “delulu” and desperation. A lot of the gameplay of NITW is concerned with marking the alienation that Mae feels towards the place to which she was so eager to come back: the mere act of existing in this game’s reality seems to ruffle our fellow citizens’ feathers – we can explore the city vertically by climbing on wires and parapets, but we get yelled at; we want to buy pretzels to feed some wild rats, but we have no money, so we have to steal; everybody is unsure why we’ve come back and what we are doing here, and has no trouble expressing it; we try playing in a band with our friends, but Mae is a bit rusty on her bass and the first time we go through the corresponding rhythm game we will very likely fail miserably, since the minigame blindsides us and is not prefaced by a tutorial. NITW presents the hometown as a solipsism for aimless Mae: she is in it, but she has no part in its life; the center of work and production (like the local megastore) are only seen in glimpses and are not normally accessible; she saunters around and wallows her days away chasing meaningless tasks, but she cannot really re-enter into local community life. Possum Spring is hometown as sterile playground, until the game takes a darker turn and reveals the unsavory penchant of the local community to consume the innocent and the outsider.

NITW is about roleplaying a failing nostalgia with bitter surprises.

I don’t know if we could get lost in a city this size if we wanted to

If both MJ:BM and NITW represent an inward motion of sorts towards the hometown, a lot of adventure games and Japanese RPGs invariably use the hometown as the origin point of an outward motion. To construct a plausible game world, effects of dilation and compression have to be juxtaposed to work properly – the smaller city followed by the bigger one, the rural followed by the urban. In Japanese RPG Legend of Heroes: Trails in the Sky (Falcom 2004) we play as Estelle, a loveable country bumpkin, hailing from a cozy hamlet called Rolent. In the prelude of the game we trawl around the surrounding countryside with her, helping people on farmyards get rid of their monster problems and assisting a citizenship that we know well and knows us well. But as soon as we set foot in the “commercial city of Bose” at the beginning of Chapter 1, the camera briefly pans across cobblestone streets alluringly dotted with all kinds of shops and attractions, hinting that what we see is only a fraction of the actual urban landscape we just entered. “Wow . . . this definitely looks like a city”, remarks Estelle, mouth agape and eyes wide open, and her sense of wonder infects us with a curiosity for whatever might lurk in this new, sprawling space.

By an effect of multiplication, each successive city in LoH seem to increment in size compared to Rolent. Your hometown sets a scale that you always unwittingly keep at the back of your head, even if you discard it out of hand as something that does not belong to you anymore. Its ways of living, its mark, still stick.

———

Giorgio Chiappa is a Berlin-based researcher and educator whose work explores the intersection of narratology, video games, and urbanism. Follow them on Mastodon.

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 189.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!