Mastering the Desert

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #188. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Architecture and games.

———

There’s order in chaos, yet also chaos in order. You can impose one or another form of structure upon the world, but the planet frequently fights back, making a mockery of your attempts to control anyone or anything outside of yourself.

There’s a town in The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom that perfectly illustrates the futility of this pointless endeavor, Gerudo Town. You can find the place in the southwest corner of the game world, looking rather forlorn amidst the shifting, sinking sands of the surrounding desert. The urban planning may not be the most interesting thing about this particular town, but the overall design is at the very least worthy of note.

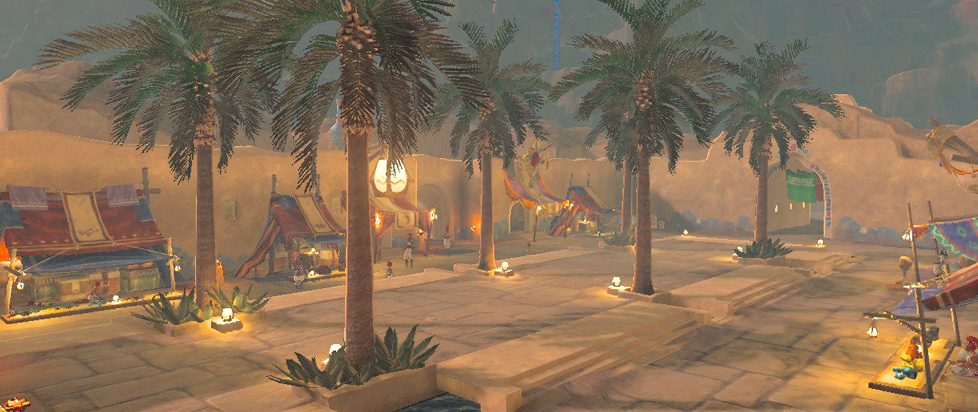

Gerudo Town was built on a fairly strict grid system, unlike any other city in Hyrule, apart from the destroyed settlement near Hyrule Castle. The walls around the slightly rectangular town rise from the desert like a challenge to the dust and debris, enclosing a series of square city blocks filled with shops and houses, carefully arrayed around a central courtyard featuring an open square and marketplace. There’s a prominent palace which opens directly onto this courtyard, built into a substantial outcropping of what I can only assume is bedrock. The most commonly used construction material in Gerudo Town is naturally sandstone.

The desert can be found reclaiming the settlement, with dust piling up in just about every street corner. The supply of water, flowing outward from the palace by rooftop aqueducts, consistently runs low enough to necessitate intervention, although not so much in Tears of the Kingdom, but certainly in Breath of the Wild. This takes place through a series of sidequests.

Gerudo Town is noticeably different from the surrounding desert, mostly on account of its urban grid, something which looks notably unnatural. While most of the other settlements in Hyrule including the highly artificial Tarrey Town make use of the various affordances and constraints of their environment, Gerudo Town clearly has no such pretense, imposing structure where none would otherwise exist. The desert presents a sea of sand on every side, while Gerudo Town tries to defy the surrounding landscape, creating a parched paradise for its people.

The concept of a grid system in urban planning goes all the way back to the settlements of ancient Greece. Amidst the chaos of conquest and the somewhat quieter processes of culture change, the Greeks brought something deceptively simple to their far-flung colonies located throughout the Mediterranean, straight lines.

Implemented everywhere from Spain to Syria, straight lines were a way of imparting a sense of reason, logic and control onto a given stretch of land. This was the basis of the pattern. Invented in the Geometric, refined in the Classical and perfected in the Hellenistic period, this rational and rapidly deployable approach to urban planning soon spread from the region around the Aegean to the Near and Middle East, then far beyond. The design was taken all the way to Afghanistan by Alexander the Great.

The direct lineage of the grid is traceable to Hippodamos of Miletus, a fifth century architect favoring orthogonal blocks, in order to integrate the social, political and economic aspects of the urban existence, reflecting a broader cultural desire for cosmic order within the chaos of mundane affairs. The power of the grid was never the pure practicality of the pattern for transportation but the deeper symbolism, grids being a physical manifestation of civilization over the forces of nature.

As the influence of ancient Greece dramatically grew following the rise and fall of Alexander the Great, grids became an ideological and practical blueprint for new foundations. They were on the other hand imposed not only upon empty land but on the much messier terrain of existing settlements, particularly in the Near and Middle East. The pattern can be seen in cities like Seleucia, Europos and Aikhanoum, urban spaces exhibiting an awkward fusion of Persian practicality and Greek rationalism.

What made the grid system especially powerful was the almost universal applicability. The layout of streets, public spaces and housing blocks followed a particular pattern, cardo and decumanus lines carving out civic identities and spatial hierarchies, reinforcing not only functionality but also ideology.

The grid system became a sort of lingua franca during the Hellenistic period, a common architectural language within a massive, multicultural world. While cities varied in scale and style, urban patterns across the Mediterranean exhibited the same rationalization of space and place, reflecting a series of shared philosophical ideals. The public square, gymnasium and theatre became the cornerstones of this identity, strategically placed on the grid to facilitate political participation and cultural hegemony. The grid was more than just an aesthetic but a form of sociocultural domination.

The legacy of the grid extends well beyond ancient history, affecting contemporary urban traditions, while providing a reminder that architecture is never neutral. The grid may seem like simple geometry, but the pattern still remains critically charged, carrying implications of dominance and control, definitely over people but also the world.

Gerudo Town is a product of this legacy. The settlement is effectively all about control, whether in terms of social structure and the clear-cut relationships between ruler and ruled or female and male, or in terms of architectural structure and the hostile interactions between city and countryside. Gerudo Town is a place filled with inherent contrast and conflict, similar to so many of our own modern marvels of urban planning.

———

Justin Reeve is an archaeologist specializing in architecture, urbanism and spatial theory, but he can frequently be found writing about videogames, too.