One of Those Nightmares Where You Can’t Move Your Arms

Spec Ops: The Line is the best-known example of a videogame that takes a conventional mechanic and inverts its meaning. Killing an enemy with a gun is one of videogames’ most substantiated and familiar metaphors for power – either the power of the diegetic character, the player’s power, or both. Shooting enemies to death in games is also synonymous with both literal and abstract progress, a way to earn new items, experience points, power ups, and other virtual wealth, and to bring your playable hero closer to his (and your) objective. Spec Ops: The Line reverses this thematic/dramatic polarity. As you progress further into the game and shoot more enemies, the physical and psychological well-being of playable character Martin Walker commensurately deteriorates. Rather than rewarding or celebrating your virtual killing, Spec Ops: The Line castigates it with increasing directness.

The problem with Spec Ops: The Line is that its efforts are directed towards a reductive, besides-the-point, didactic dead end, i.e. an assailment and judgmental evaluation against the inevitable (and structurally unavoidable) actions of the player. It conflates the player’s desire to play the game with giving a virtuous assent to the actions the game is forcing us to vicariously complete, as if to say that by turning the pages in a copy of American Psycho, or not pressing “stop” on our copy of Psycho before the shower scene, we somehow become moral endorsers for Patrick Bateman and Norman Bates. Spec Ops: The Line is an especially shortsighted characterization of The Videogame, whereby interaction is considered indivisible from inhabitation – a game that assumes that the only reason the player might do something is because they find it narratively, dramatically, spiritually and morally agreeable. It’s obtuse to the idea that game-makers might create opportunities for interactions that have bearing on the subjectivity of the world and the character, and that players might do things in games not because they want to extend and effectuate themselves, but because they want to ‘perform’ in such a way that is assonant with the character: I’m personally teetotal and I’ve quit smoking, but in Red Dead Redemption 2, I will often take Arthur Morgan to a bar and have him light up a cheroot because it feels like it’s what he would do. We don’t do things in games only because they are what we want to do, or we think they’re “right,” or we think they’re justifiable, or they’re an extension of a need to express ourselves. We may do things in games because we feel those things are what the character would do, and the gratification we get is not from a banal, onanistic self assertion, but from feeling participant in the development of the character and the character’s story as entities separate from ourselves.

I’ve written before about how Spec Ops: The Line is considerably more powerful if you play it entirely from the perspective of Martin Walker, without regard for what it says about you as the player or about the nature of videogames. It’s tragic that a game which has themes of genocide, murder, insanity, PTSD and death – death of all kinds – has ultimately become, owing both to its creators and a lot of posthumous criticism, remembered for being a game about videogames. If there are moral quandaries about videogames – their construction, their nature, their effects and their methods of representation and recreation – accessing discussion of those moral quandaries via illustrations of mass murder feels ironically narcissistic. Part of the Spec Ops: The Line thesis is to assail the (theoretical, traditional) videogame player’s intentions: “Look at what you’re willing to do to get your thrills.” But you can turn that allegorical desk lamp back in the faces of the game’s makers: “Look at what you’re willing to put on the screen, and make people do, just so you can talk about videogames and by extension yourselves.” It would take more guts to make the game about genocide.

This is why I’m reluctant to say that one of the greatest strengths of Anoxia Station is in how it inverts, or subverts, videogame mechanics. I worry that, because of Spec Ops, the concept of turning gaming mechanics inside out has become indistinguishable in our heads from a crude, sledgehammer-morality kind of satire on videogames. If I say that one of the reasons that Anoxia Station is perhaps the best game of 2025 is because of how it reverses the tropes of city-builders and strategy games, my concern is that it makes Anoxia Station sound like it’s a game about those kinds of games, and that the imaginations of its two creators, Yakov Butuzov and Daria Vodyanaya, extend only so far as parodying other game genres. On the contrary, the effect of Anoxia Station is most keenly felt if one is familiar with games like SimCity, Cities: Skylines and Civilization. While Anoxia Station is not an anti-4X or anti-city-builder game, it certainly uses the mentality that a player might carry into one of those types of games as its springboard.

In those games, construction, irrigation, extraction, expansion and the other precepts of making society and industry are symbolized as imperative. The goal is to get bigger, get richer, and get more technologically, logistically and socially advanced, and the completion of those goals – or incremental progress towards those goals – is rewarded. It would be inaccurate to say that in these games colonization or encroachment on the natural world are recreated with uniform enthusiasm and endorsement. Across the real time strategy, city-builder, 4X and strategy genres there are games that confer punishments, or at least partial in-game sanctions or implied condemnation, for over-expansion and commodification. In SimCity, rapid, unmitigated industrial growth will cause progress-stymieing pollution; zealous conquerism in Civilization is met by the martial resistance of other leaders, and can backfire so entirely that your armies are defeated, your capital city is captured and you lose the match. Nevertheless, the “4X” in 4X games stands for explore, expand, exploit and exterminate. In the overwhelming majority of these games, victory is only possible through the consolidation and harvesting of natural resources. The more land that you occupy, or oil that you drill, or wood you chop, or stone you mine, the higher your likelihood of building towards success.

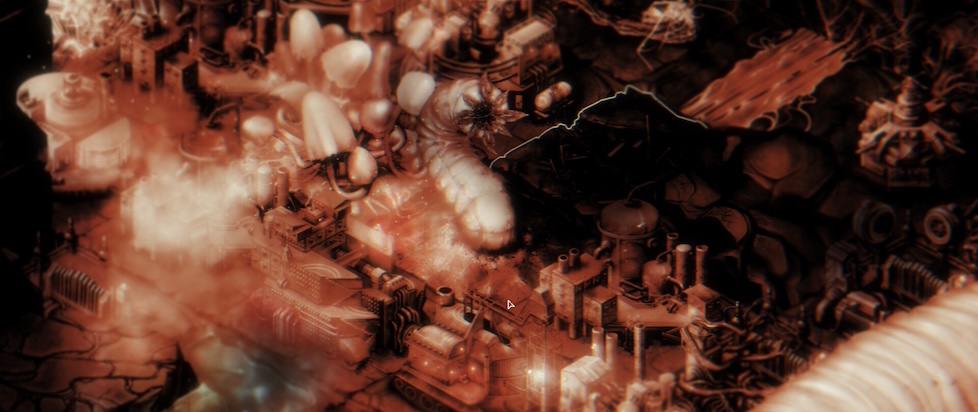

The central dynamic of Anoxia Station is similar, insofar as the construction of buildings and the extraction of natural resources like water and oil are both necessary for success and rewarded by the game. The goal is to reach the end of the level, and to reach the end of the level you invariably need to build something, and to build something you need raw materials. However, the resources you procure in Anoxia Station are all utilitarian. The water is to drink. The oil is to power convectors and filtration systems so that your small team of scientists, miners and engineers doesn’t suffocate, or die from radiation poisoning. Everything you build has a life-guarding function – you don’t build for expansion or luxury. Rather than a symbol of power or wealth, the bigger your “city” becomes, the more it symbolizes your vulnerability; the more it demonstrates just how many appliances are necessary for you to stay alive down here, and how dependent you are on their functions. In SimCity, Civilization, et al., the larger your in-game construction, the greater your sense of dominion. In Anoxia Station, the inverse is true: you need to build more stuff because you’re further from the surface, further from safety, and in greater danger of extinction. Rather than an empire, you’re building your iron lung.

Anoxia Station has its own version of the “fog of war” system that you find in Civilization, Command and Conquer, Age of Empires, and other strategy monoliths. You cannot see the entire map, and may only open new sections by allocating time and people to drilling through surrounding subterranean rock. When a rock face is destroyed, you may now view and access a designated number of hitherto obscured map tiles. In almost every strategy and RTS game, as well as additional, usable terrain, pushing back the fog of war will often reveal hidden enemy units or outposts, perhaps sparking a sudden conflict for which you are unprepared. Anoxia Station is no different, but when you unexpectedly “activate” a previously unseen opponent, the effect is impactful beyond mechanics.

Anoxia Station’s monsters are frightening. Some prey upon established phobias – spiders, snails the size of houses, giant moths that attach themselves to your buildings and chew through the walls and beat their wings. Others defy explanation. A grub that fills half of the map – it never moves, but if you right-click on it, an image of a baby’s bottle appears, and you can feed it a member of your expedition. There are skeletons of giant fish, which are somehow alive and able to autonomously reproduce, so that in three or four turns they overwhelm your screen. One of the snails seems capable of grotesque and subsonic human speech. Several thousand feet beneath the Earth’s surface you find the wreckage of a World War 2-era bomber plane. Encased in one hunk of rock is a still-living, truck-sized eel. When you discover one of these creatures, all of the alarms in your base are activated at once. The screen shakes. The animal wails. I’m reluctant to try to translate the effect of Anoxia Station’s various sounds into words, not because the language to describe them doesn’t exist, but because they’re seemingly designed to generate a nonverbal bodily reaction, a primordial jolting rather than considerate homosapien thought. On the contrary, I am willing to assign the sensation catalyzed by Anoxia Station’s monsters one adjective: formicate, which describes the feeling of insects crawling on or beneath your skin.

And so the act of expansion becomes fraught not only with mechanical peril (you have to expend turns and resources to eliminating the monsters) but fear and unease. When a game attacks the player mechanically – perform X action, and it will cost you Y in-game resources – that can also produce an emotional response. Anoxia Station however redoubles that effort, so that constructing outwards is immediately and violently precarious for the player’s nerves. A simple way of thinking about it: every time you remove a fog-of-war tile in Anoxia Station, you risk a jump scare. But that is inefficient for describing how the game’s monsters really make you feel. They provoke feelings of discomposure, a sense that you don’t really know what’s going on. It’s a reverse of the sense of supremacy that games of adjacent genres typically inspire. As you build wider, you feel smaller. The more you discover, the less you feel you understand.

That feeling is accentuated by the game’s visual framing. When you play Anoxia Station, it’s as if you’re “watching” through a CCTV camera, the lens of which is occasionally obscured by condensation and electronic interference. The maps are small. The perspective is narrow. Your buildings are erected in point-blank proximity to one another, and the limited, pseudo 4:3 point of view makes it impossible to gain a comprehensive visual vantage over the topography. Combined with those condensation effects and the meters that tell you your oxygen is getting thin, the temperature is going up, and there’s mercury gas in the air, Anoxia Station is a simile for panic.

You can see how all this might be interpreted in a Spec Ops: The Line-ian way, how you could take Anoxia Station as an assault on the various precepts of player agency and how that agency is expressed and facilitated in strategy games. The player is obsessed with himself and his own ends. The strategy game’s mechanics empower and provide routes for the exploration and substantiation of that obsession – the genre’s prototypically exhilarated attitudes towards expansion, colonization and subsumption are the theological justifications for the player’s self worship. It’s very possible to argue that Anoxia Station, where the actions and philosophies that are traditionally rewarded by strategy games are in various ways “punished”, or at least where their spiritual grandeur is mitigated, is a game about these kinds of games.

Games about games – Spec Ops: The Line, BioShock, The Beginner’s Guide, The Stanley Parable, System Shock 2, Superhot – share a common didactic goal. They encourage players and critics to evaluate in more detail the nature of the videogame, to consider, as much as its limitations or esotericisms, the videogame’s possibilities. By ventilating questions regarding the nature of videogames, these games are an invitation to take games more seriously – to regard them as artistic texts with the same properties, potencies and abeyant potential as any other artistic form. They may crudely scold the player for doing what he’s told, and has no choice to do. They may also wrongly conflate functional necessity with spiritual endorsement (pressing an input to make the game move forward, to make the game “go,” is nowhere near the same thing as pressing that input because you have some kind of moral conviction towards the output it will create). Nevertheless, these games are eager to make you consider their possible meanings, to transmit the idea that a videogame may have thematic and dramatic volume.

But if part of the intellectual project of these games is to germinate deeper consideration of games’ artistic opportunities, scrutinizing the nature of videogames themselves is surely the most uninteresting and unlikely topic to actually activate that consideration. This is a blunt extrapolation, but if the goal is sell people on the idea that videogames as artworks can speak to complex ideas, and should not be confined to the arcade, the basement and the fringes of thoughtful culture, games about games pull in the opposite direction: they make games, as a form, seem incestuous and occult, and turned inward towards self-interested questions rather than outward to the complex and worldly topics that would make greater demand their makers and audiences. It’s perfectly worthy to interrogate the structural and behavioral conventions of videogames, but that interrogation would be more sophisticated, and yield more useful discoveries, if it were rested on different questions. Rather than asking “what does this game say about games?” and “what can we therefore extract regarding games’ potential to explore themes of X, Y and Z?”, it’s more direct and more fruitful (and I’d wager more interesting to players generally, and therefore more conducive to profit) just to make the games about X, Y and Z.

Anoxia Station is a game about fossil fuels, environmental destruction, and the existential threat of global warming. Instead of just satirizing the typicalities of strategy games and the established strategy game player mindset, it’s a primal scream about the oblivion heralded by consumption. But then I also take it as a game about games about games, an alert that although those interpretations may serve some limited exploratory purpose, they can also become casuistry, unlikely to fulfill their would-be purpose as compared to more exterior thematic analysis.

———

Edward Smith is a writer from the UK who co-edits Bullet Points Monthly.