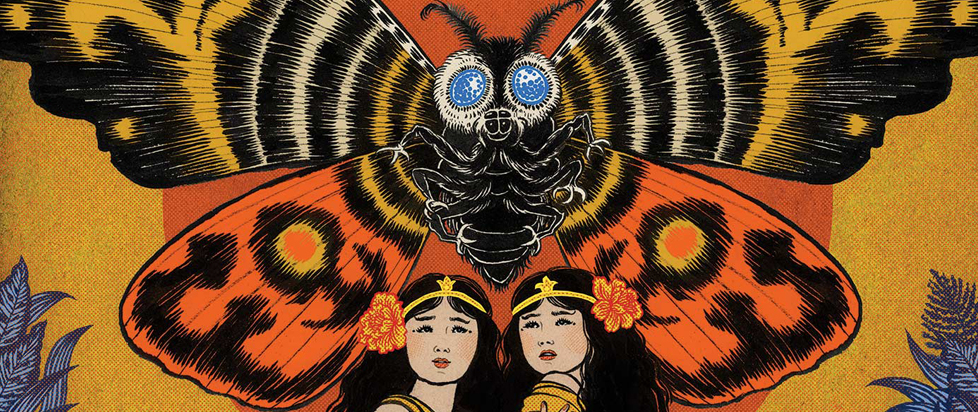

Oh Mothra, Advance With Silk and Song

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #176. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Analyzing the digital and analog feedback loop.

———

Mothra is not just the reigning queen of kaiju, but also the queen of the “kawaiiju.” Arguably she’s as important to cute culture in Japan and abroad as Hello Kitty is and is perhaps the reason that Pokémon and Aggretsuko are phenomena as well. Mothra is at once an icon of ritual and tradition as well as one of feminine transgression. She is a goddess, yet she is mortal, each of her incarnations effectively sacrificing themselves for the sake of her people and the land, ravaged by atomic technology. She can resurrect herself via asexual reproduction and therefore is a symbol of rebirth and hope.

I’m relatively inexperienced in kaiju lore and culture, but I’ve always been aware of Godzilla and Mothra. The two in my mind are the pinnacle of this sci-fi subgenre. My first encounter with kaiju wasn’t via these key figures, however, but through references to the concept of monsters that avenged the earth in Final Fantasy VII. Gaia or The Planet’s protectors, simply called Weapons, were my official (although meta) introduction.

My second encounter with kaiju was via a 1990s figure of Godzilla, which my dad tried to give me as a child. I say try because ultimately the toy (try not to cringe too hard) had to be gifted to a friend of mine – I was too terrified of the recording of Godzilla’s iconic cry to play with it. The roar struck a chord of primal fear in me, which I suppose is a testament to composer Ifukube Akira and his team’s talent. Although I now find classic Godzilla’s original rubber suit design rather cute (non-derogatory, I simply love monsters), I still experience an echo of that fear when I hear his cry.

I vaguely remember the same childhood friend who received the toy watching one of the reruns of a Godzilla franchise film with me. This film might’ve been one of the “vs.” ones featuring multiple kaiju, including Mothra and Rodan (or was it Gamera?). For a while afterwards, I wouldn’t engage very much with the genre, despite liking the underscoring of environmental themes. The closest I got was watching Neon Genesis Evangelion when it first became available to rent in Canada at our then-local video store and anime mecca, Jumbo Video.

Decades later, while perusing various art websites for inspiration, I stumbled upon photos of Virginie Ropars’ one of a kind statue of an anthropomorphic Mothra, similar to the fan-art form known as gijinka. Gijinka is often focused on portraying animal characters as human girls or women, especially of the moe variety associated with not just otaku culture but shojo genres about coming of age and transformation. I’ll return to this last aspect of transformation, but suffice to say that this lavish polymer and fabric statue will live forever in my memory.

Despite having few memories or opinions of Mothra beyond loosely knowing her as a counterpoint to Godzilla’s hostility and an erstwhile and symbiotic ally of his, I was awe-struck. Mothra’s humanoid form showcases crimson silk and lace-edged robes, evoking her original silk moth form. This aspect is especially apparent in the ivory bodice which is exoskeletal and recalls the thorax and abdomen of the insect. Her hairstyle is vaguely reminiscent, in conjunction with the sumptuousness of her gown, of a Tayu–a figure that in Japan is often erroneously conflated with the high class courtesan Oiran. Tayu were figures more akin to the Geisha tradition. Tayu were so highly respected at one point in Japanese history that they were allowed to be present in the emperor’s presence at court. Tayu were also responsible for keeping many artistic traditions alive and often apprentice two young understudies, known as Kamuro.

This is suitable for Mothra because not only is she a monster who is revered by many, she is a monster who is also attended by two understudies – in the original film and the story that was written for it, Mothra is preceded by twin fairy priestesses. These fairies are called Shobijin or “Little Beauties” by the humans who encounter them and they speak on behalf of Mothra using telepathy to deduce what ideas and feelings people hold most important. As such, even though they are not children, like the Kamuro they are an extension of Mothra’s ideals in a similar way. And Mothra protects them with her great powers of hurricane winds produced by her wings, poisonous spore-like scales and of course her silk threads (used both to transform from an equally powerful larval state to her giant moth form).

The Ropars’ statue manages to distill Mothra’s elegant monstrousness that I find really compelling. She’s akin to Giger’s Xenomorph Queen here, both bizarre but evoking a kind of reverence. In an interview by John Fleskes of Flesk Publications, which publishes curated contemporary art in its annual Spectrum series, Ropars states that she’s less interested in the darkness of her bizarre feminine figures. She’s more concerned with natural forms and how mythology often featured divinity surrounded by wild nature, which is morally gray. Ropars is formerly of the videogame industry (she was laid off and never returned since around 2001 or 2002) and is inspired by multimedia art communities that exchange ideas and fight for social ideals, like England’s Arts and Crafts movement and France’s Decadence era. I’m not surprised that these philosophies led to the creation of her Mothra statue, but I’m also surprised at how this work also speaks to the subversive nature of kawaii and the transformation of feminine identity and culture in Japan.

A lot of people associate the term kawaii and its culture only with things they deem excessively cute, pastel and infantile. This denigrates and flattens a phenomenon which is actually vital to the evolution of youth culture in Japan as well as alternate modes of expression in art and fashion. Matt Alt in his comprehensive study of Japanese pop culture and its global influence, Pure Invention, notes that even the linguistics of kawaii is complex and separate from the English linguistics of the word cute. Cute is derived from ‘acute’ and wasn’t always used to point out something adorable or pitiful.

The “earliest known usage of ‘cute’ from the 1700s [is] as a synonym for ‘shrewd,’ a clever and conniving image that survives in phrases like ‘Don’t get cute.’” Kawaii and the culture attached to it is more purely about the aesthetics and philosophy of adorableness, with the word’s first modern usage in 1914 being connected to the famous fashion boutique Minato-ya and its redefinition of femininity that drew upon both traditional beauty and foreign culture at once. Previously, Alt notes, young women would be referred to as kirei (attractive).

When I refer to kawaii culture in this piece, however, I’m thinking of how the legacy of the Minato-ya feeds into the current sense of kawaii being something empowering and an alternative to traditional beauty standards. Catherine Marie Rose has a wonderful sociological study on practitioners of styles like fairy-kei and decora and how kawaii culture is not just a commercial aesthetic practice, but a form of self-care and finding communities of like-minded creatives. There are of course more fraught and commercial aspects to kawaii culture and related fashion styles like Lolita as well, a concept that is explored with great nuance in So Pretty, Very Rotten, a collection of textual and visual essays as well as interviews by key figures by Jane Mai and An Nguyen. Largely, however, kawaii culture is politically progressive and has ties to the student uprisings of the 60s, which Alt explores throughout Pure Invention.

Mothra and Mothra vs. Godzilla were created in the ‘60s and I don’t think this is a coincidence – take the Shobijin’s actresses for example. They are identical twins Emi and Yumi Ito, who together were known as the musical act The Peanuts. Their first single was “Kawaii Hana” which harkens back to that early modern legacy of kawaii culture, combining a traditional subject of pure beauty in nature with foreign composition and language. The Shobijin are at first defined solely by their beauty, Fukuda the journalist telling Chujo that unless they are terrible, the press always refers to women as beauties. “It’s good for our business and all that, you know.” Yet despite the greedy antagonist Nelson capturing the girls and exploiting them as a sideshow wonder of the atomic age, he cannot contain them and their connection to Mothra.

Kawaii culture is powerful and often underestimated, usually by men or people who have internalized sexist beliefs. Pay attention to the human women as well in films Mothra features in – they are often the ones leading the way forward, even if they are cast as side characters. In Mothra vs. Godzilla in particular, it’s the photojournalist Nakanishi Junko’s plea on behalf of humans that sways the Shobijin to call upon Mothra, even knowing it will lead to this incarnation of Mothra’s doom.

Mothra’s femininity is more aligned with the noble maiden that Arika Takarano, the vocalist of ALI PROJECT and an important figure in the Lolita subculture, describes. In her essay, titled “Oh Maiden, Advance with a Sword and Rose,” she speaks directly to the reader of Gothic Lolita Bible (presumedly a feminine-presenting person) as someone destined to express their beauty in a unique way.

But she also ties this identity to an ethereal state of potential transformation: “You exist in a cocoon. The light of the sun and the glistening of the moon gently fall upon you there.” She gently encourages the maiden to emerge as their highest form, someone whose lacy and silken garments are not only an expression of their high intelligence and respect for themself, but someone who possesses a “well-honed sword” with which one can protect themself and the vulnerable. She also speaks of the maiden’s “elegant wings with the luster of velvet” and that even if someone were to hurt them that they will land in the right place. The maiden is beautiful because she knows her individuality and her like-minded community through and through. She is not beautiful to attract men, but to express her truest self. Kawaii culture is so influential to Japan, in fact, that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs appoints people like Aoki Misako, also an important Lolita figure, as Kawaii Ambassadors.

Mothra relates to kawaii culture in that she’s a unifying figure, making other more destructive kaiju direct their power towards external instead of internal threats. She uses her powers to protect her own and judges people based on their character. The solution to stopping her from destroying Tokyo and the fictional New Kirk City in search of her lost priestesses who called upon her with a ritual song for help, is for the humans to cooperate on finding a way to communicate with her.

Weirdly, there’s a Christian bent to this conclusion of the origin film’s plot here, with the Japanese journalists conferring with an eccentric and brilliant linguist who discovers that the symbol for Mothra represents both the sun and a cross. They paint this symbol in a church plaza and ring all the bells as she flies near, in effect mimicking the fairies’ musical summons and returning the Shobijin to her. There’s a colonial undertone to this scene, in the sense that throughout the film there’s a problematic noble savage-like quality to the indigenous people of Infant Island, where Mothra is from.

She’s noble and maidenly, like Takarano’s maiden but also a revered figure that evokes classic Japanese ideals and culture like a Tayu. At once, however, there is a sense that Mothra’s femininity walks a thin line between an alternate and powerful expression of gender roles and a more staid and essentialist one that reinforces stereotypes of fragility and sacrificial motherhood. Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019) made the mistake of leaning into Mothra as strictly a sacred mother figure, one who is defined by her symbiotic and possibly romantic relationship to Godzilla.

Mothra’s beauty is ephemeral yet constant throughout her lore, like the silk she weaves and that has been a signifier for both Japanese traditional elegance and unfortunate exotification in Western colonizer nations. Her beauty is that of the afterglow of apocalypse, the persistence of nature with or without the anthropogenic presence. We are easily caught in her symbiotic web of influence and her gentle divinity. She’s a pagan and primordial goddess devoid (or at least resistant in most incarnations) of the white or male gaze. Her appearance and presence are powerfully kawaii and in her stories, femininity is tenacious and centered in her narrative spool.

———

Phoenix Simms is a writer and indie narrative designer from Atlantic Canada. You can lure her out of hibernation during the winter with rare McKillip novels, Japanese stationery goods, and ornate cupcakes.