1982

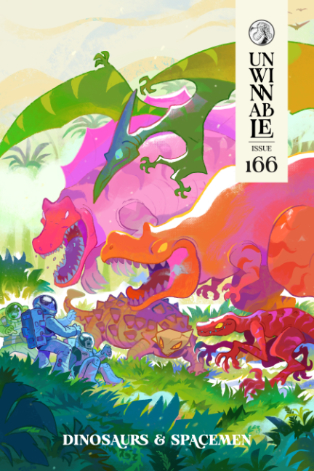

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #166. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Kcab ti nur.

———

This month, it’s time to get our Forces on and step on over to 1982 to discuss two films which tell the stories of a Black relationship on each side of the Atlantic.

In Kathleen Collins’ Losing Ground, we follow college professor Sara (Seret Scott) and her husband Victor (Bill Gunn) and see their vision for the future of themselves and their relationships strain as they go on holiday during the summer to a leafy mansion in the country. Fellow Black trailblazer Menelik Shabazz’s film Burning an Illusion also covers a straining Black couple, this time with Pat (Cassie McFarlane) and Del (Victor Romero) dealing with the realities of being young, Black and in love in Thatcherite London.

In some ways Black Love has become marketing, something that can be attached to hashtags, put on t-shirts and covered in softly lit talking head documentaries. That marketing flattens complex realities and produces the idea that heterosexual individualized Black love can function as a sort of panacea. Where these two films find their success is in complicating these relationships and therefore showing their central characters as real full people not product, showing the sharp corners and complicated realities of what it means to be Black and in love, and how this kind of love doesn’t exist outside of broader societal power and pressures.

At the core of both of these films is an understanding of the complexities of gendered power. In Losing Ground both halves of the central couple who drift away from each other, but it is Victor who is brazen and pushy with his attempted muse. In Shabazz’s film it is Del’s hand that brings the physical violence, to the relationship. Patriarchy pierces through perceived protective bubble and makes the lives of these women worse.

However, the misogynistic and sometimes violent behavior of these men is never shown to emerge from nowhere, or worse still some inherent component of Black masculinity. Instead, it is specifically situated within their individual personalities and broader structures. With Del, he feels disempowered by racism and reaches for the power he can exert – patriarchy. There’s a sort of petulance to Evans’ performance which shows the pathetic grasping nature of his violence. And yet we are never allowed to forget that this male petulance can have serious violent outcomes.

Bill Gunn’s incredible performance as Victor really emphasizes petulance as well. He showboats when he dances, he openly argues of a woman who isn’t even dating him, his head is constantly in the clouds and far away from his wife’s emotions. Yet Collins’ portrayal is still empathetic and constricts this as emerging from a deep emotional dissatisfaction. He is desperately seeking a life where he can make art that clicks, that he believes in, that he is satisfied by, where he can find the inspiration that finally fixes things. So, until he gets that he will throw his toys out of the pram and onto to the head of his wife. He’ll break sandcastles, he’ll push boundaries, he’ll be a nuisance in the lives of everyone around him till he gets there. And the beautiful tragedy of it all as constructed by Collins is that Sara is also asking many of the same questions in her own search for ecstasy and meaning.

Having these complicated dynamics brought through by the range of all the actors involved, means that we don’t submit to a shallow understanding of Black liberation in which Black women are expected to ignore patriarchal violence for the sake of an abstract greater good. Here both films clearly draw on the work and discussions happening contemporaneously in Black feminism pushed by thinkers/activists like Olive Morris (who died a few years before the film was made) and Audre Lorde.

Love can’t solve everything either. The external is always there. The trial judge who refuses to reduce Del’s sentence does not budge just because he and Pat are in love with each other. Love alone cannot reconcile the fundamental differences at the core of Kathleen Collins’ delicately crafted characters. Love can’t block the bullet which embeds itself in Pat’s leg.

Crucially the conclusion here isn’t that Black love (in whatever form that takes) isn’t worth it. Where Pat is able to find herself is in a radical political education and sisterhood with other Black women. It’s that’s sort of community which means that even when Pat is shot by racists, she is able to be supported and have her people keep her going. There’s no greater love to be found than that. That can’t be found in the halls of the upstate quasi-gothic mansion which Victor is convinced will be his salvation.

The most emotionally resonant moment in Burning an Illusion (and certainly the most sensitive acting work from McFarlane) comes towards the end. Pat spots a worse-for-wear man on the street whose previous presence in the film had been as a menace who would persistently catcall her. He doesn’t remember her – or pretends not to. She offers him a pamphlet for her organization and some resources to get him some help. He refuses the pamphlet and walks away.

It’s the ultimate demonstration of the ideas of love and empowerment streaming through. Love and solidarity allows Pat to finally engage him on her own terms. And it doesn’t work! Because even radical Black love is no panacea. But it’s worth trying and it’s worth fighting for.

———

Oluwatayo Adewole is a writer, critic and performer. You can find her Twitter ramblings @naijaprince21, his poetry @tayowrites on Instagram and their performances across London.