The Graffiti Wall

I feel like my articles perhaps say more about my mental degradation than they do about games, and that they’d be better delivered on torn and variously sized scraps of paper, written in thick pencil and all capital letters, or maybe pinned to the walls of the basement of a house where the taps dispense brown water and if you stands on the stairs they break. But anyway, if this is an exercise in idiosyncrasy and impenetrable esoterism and paranoia and maybe mania then fine, that’s okay, because it might still mean something to people, and might still be right, as in accurate, as in correctly observed.

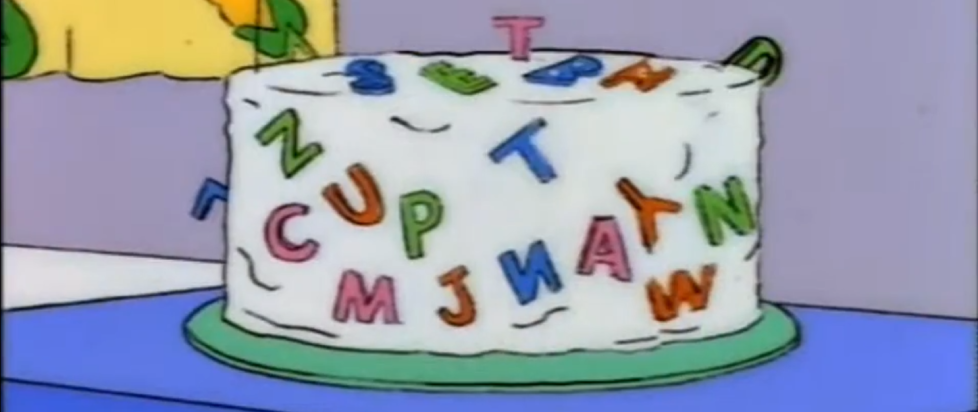

The graffiti wall is this thing local governments and councils put up where you can go and write graffiti and deface and do what you want to it and it’s not illegal, the idea being it stops people from doing actual structural or environmental or architectural or aesthetic damage to buildings, walls, etc. that actually matter, by giving them an outlet for their graffiti on a place where it’s allowed. And did you ever have to wear a uniform at your school? Part of the reason we make you do that (I was a teacher once) is because it has this really useful psychological effect, whereby we know that young people are going to break the rules and try and cause problems and generally act up, so we give them uniforms as – again – a kind of designated venue or drain or emanation for that impulse, i.e. they have to do something, have to defy the rules of something, so we make them wear uniforms so they can tie their ties too short or untuck their shirts or put on white trainers because they get to feel defiant that way, and to assert and asseverate a disobedience and rebellion and personality, but not in a way that really interferes with anything major. They untuck the shirt, we tell them to tuck it in, there’s some here and there, but it stops them from skipping classes or something worse, because that back and forth regarding the untucked shirt is sufficiently individualistic for one day.

And that’s become, I think, the function of culture – or the culture of culture – in our century, an allotted means or domain or kind of theater where we’re granted the impression of opinion and self and power and contumaciousness but only to prevent or distract or generally just tire us out from committing any greater crime against whatever system you care to name, economic, political, social, and so on. I feel like this extends actually to things like democracy and freedom of speech, like we can vote and demonstrate and say what we want, but only so we’ll feel sufficiently expressed and filled and satiated with freedom that there becomes, psychologically and emotionally, significantly less of an urge to do anything more. It’s like we’re encouraged to talk and rally and rouse and given tools to talk and rally and rouse to stop any change. And you already know what I mean – we can all feel it, everywhere. And even the ostensible victories start to feel diversionary and conciliatory and anesthetic and part of some part of some immeasurable, boundless maneuver to prevent anything from happening. And you don’t know who by or what for, and but that’s the point, but whose point and to what end, you don’t know.

It’s like we have a tremendous sense of power and control now over things that ultimately, even if they were completely revolutionized, wouldn’t do anything to transform the economic and political situation, and what that does is also nullify the sense of need or appetite or energy or perspective for when it comes to maybe doing anything to transform the economic and political situation. Yet when you realize this, it’s a realization that has a profound and even more greatly nullifying effect, because what it means is realizing that all the fronts on which you have been battling and all the ways you perhaps thought you were contributing to anything – to change of any description – actually haven’t catalyzed or caused anything at all, so as you realize that your fighting and talking and expressing up to now have perhaps been part of some some wider program of distraction, you discover also that all your fighting etc. up until now has therefore been worthless, which makes all fighting or expressing or whatever feel worthless, so even if you did now know where to actually aim your efforts, you just don’t feel like it any more, because the discovery of the knowledge that your efforts until now have actually been used against causing too great a psychological pain – it makes you too depressed to care any more.

What videogames do is make you feel like your choices and your decisions and what you want are the most important things. Design your character, play your way, explore at your leisure, influence the narrative, do what you like, and so on. The quality of a videogame is often judged correlatively with how much it allows you to do things that you want to do, which is why “linear” is often regarded as a pejorative whereas everything that sells big numbers lately is an open-world RPG or live-service game where you, the player, control it all and get to do what you want. So games become another closed avenue of choice and power and expression, another designated area in which we can say and do and be what we want, and affect change and influence over a system, i.e. make the world and the rules of the videogame serve us and our fantasies.

You know, it’s not sufficient to create the distraction – the distraction has to provide the illusion of not being distracted, and, in fact, of having your individualism or your thirst for change and influence slaked. It’s that awful paradoxical virtual world thing, where we have unprecedented freedom and self, but only in a place or places where our freedom and self have no bearing on the world actually. That’s part of what the modern videogame has become, a simulacrum of individuality and power and effectiveness and agency, but as a means of neutering and kind of safely expelling those impulses for power and effectiveness and agency away from the actual world. Do your agency and your individuality and your power to create change over here, so you don’t spill any of it on reality.

———

Edward Smith is a writer from the UK who co-edits Bullet Points Monthly.