Three Paths Towards Approaching Mental Illness in Videogames

Too often, it feels that videogames employ the specter of mental disorders as a kind of “bogeyman” shock tactic. Asylum levels are popular, as are plots in which the protagonist’s own sanity is brought into question to discomfit the player. Rather than deconstruct this abjection of mental illness that’s so prominent in videogame history, I thought I’d look instead at three different games I’ve played which opt to take a less antagonistic view of the subject. These games differ greatly in their approaches, but each provides its own alternative to the more common portrayals and could be said to focus more on the broader theme of “living with mental illness.”

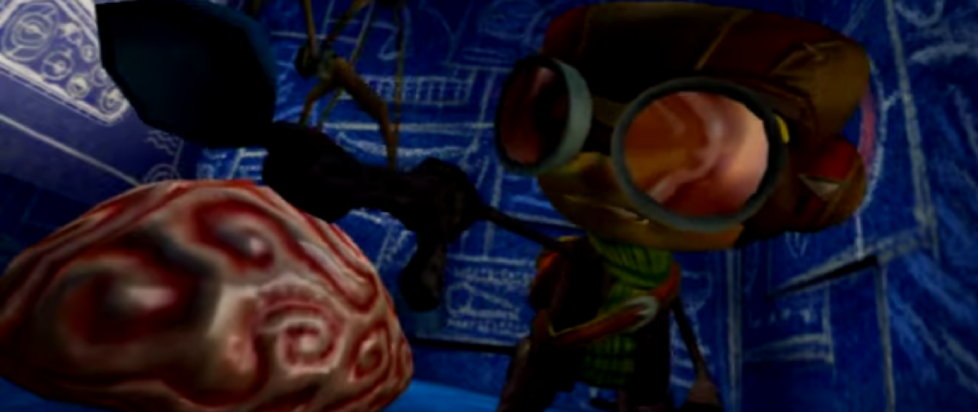

Psychonauts (2005)

From its very title, Psychonauts makes it clear that it’s a game about the internal psychologies of its characters, which are intimately tied to their actions within the external-world plot. The main character Raz embarks upon a journey to become a “psychonaut,” a kind of hybrid psychologist/secret agent with the ability to literally enter the mind-spaces of others. The internal spaces of the characters’ consciousnesses are represented as action-platforming levels filled with dream imagery, quirky characters, nightmarish enemies, and no shortage of odd collectibles.

Perhaps most interestingly, almost every character in Psychonauts, hero or villain, is suffering from some mental affliction, including Raz himself. Raz’s mission in each level of the game is typically to help the character whose head he occupies to sort out their problems by fighting representations of their inner demons. Not every character “gets over” their illness, but the result is usually that they can turn that illness around to do some good in the world instead of harming themself or others.

The game does, however, take a specific historical approach to the mental illnesses it represents: by finding certain collectibles within the game’s levels, Raz can learn more about the traumatic memories of the individuals he’s dealing with. These memories are often implicitly linked to the onset of the characters’ afflictions. This particular view of mental illness feels very Freudian, locating the origin of illness in a generalized notion of “trauma.” While an interesting lens to view video game characters through (one that any student of literature might find familiar, if overly so), this Freudianism could also be one of the game’s greatest weaknesses in its portrayal: it never really acknowledges that there are some mental illnesses that don’t come from any identifiable trauma, but are nonetheless difficult for the individual. Another possible weakness is the light-hearted, cartoonish tone with which these traumas are treated, threatening to trivialize the issue of living with something like (to cite a specific in-game case) schizophrenia. Still, the game is distinct in its approach to mental illness and displays a unique personality throughout.

Persona 5 (2016)

Every game in the Persona series I’ve played has centered around some kind of relationship between people’s mental states and the society around them, but Persona 5 might be the most in-depth exploration of these themes to date. As in Psychonauts, you play as a young person with the quasi-magical ability to enter people’s minds, but where the former game delved into the portrayal of a variety of specific mental illnesses, Persona 5 focuses on one particular affliction: the delusions the game’s villains suffer from regarding their place in the world.

Persona 5 is a strange beast, part dungeon-crawling JRPG, part visual-novel-style life sim, with the player’s abilities in the dungeon being linked to their progress in the life sim. As a teenager falsely accused of a crime by an influential figure, your main task in the life sim setting is to meet people throughout Tokyo and build relationships with them. Those relationships in turn provide you with more powers in the mental worlds you explore with a team of other teenagers, fighting against “shadows” to steal the mental “treasures” of the world’s deluded villains (who usually threaten the main character in some way through the abuse of their power) in order to bring about a “change of heart”, effectively causing them to repent of their past behavior and turn over a new leaf in life.

This link between the social life of the main character and his battles in the game’s mental worlds suggests an approach to mental illness quite different from that of Psychonauts: instead of portraying the mentally-ill individual’s mind as containing all the keys to fighting that very mental illness, Persona 5’s hybrid gameplay implies that the mental world cannot be easily separated from its social context. The proof lies in the way the game expects you to socialize, make connections and help others with their physical-world problems to get stronger in the mental world. As the main character and his team work to free the villains of their delusions, the story and gameplay seems to convey the message that by being a good friend (or citizen), an individual can effect social change and ease the burden of mental illness by making the world a more welcoming place, one more conducive to mental health. A late-game twist makes the connection even more explicit by revealing that the villains’ delusions only developed in the first place due to the pressures of a negative society surrounding them (there’s some Gnostic “false God” narrative in there too, but we can safely set it aside as a metaphorical extension of this phenomenon).

There is, however, one main issue I take with the game’s social perspective on mental health: in reality, this social change model might not be enough for everyone. Some people’s mental health struggles are intensely personal and internal, and changing the world around them can only do so much. Further, some of the activities and relationships the game encourages the player to engage in to make the world a “better” place can come across as oddly normative and conformist in their prescriptive senses. Finally, it must be said that for a game that encourages the player to go out and forge relationships as a way of combating existential loneliness, Persona 5 could ironically prevent them from doing that in real life as they stay inside chipping away at the game’s long run-time – low-balled at about 100 hours for the main story! Still, I admire the game’s recognition of the important link between mental illness and the society it exists within.

Celeste (2018)

The most recent game I’m exploring here takes a slightly different approach from the other two: instead of looking at mental illness in a variety of characters or in a broader society, Celeste chooses to focus specifically on mental illness in one individual, its main character. Just what this mental illness could be is not explicitly stated in the game, but many players have (quite reasonably, I think) read protagonist Madeline’s journey to climb a mountain as a metaphor for dealing with depression. As a metaphor, it’s simple and not even necessarily original, but it’s an effective one, and works well in smoothly merging the story and themes with the gameplay; the player works to move Madeline physically upwards through platforming stages as she tries to climb out from a “low” mental place.

Besides the focus on a singular character, the other major difference that sets Celeste further apart from Psychonauts and Persona 5 is that it’s not at all interested in trying to investigate or explain the “origins” of mental illness. Madeline is depressed, but we don’t necessarily find out why – there’s no past trauma or social dilemma on display in which the player can locate the source of her problem. The game is instead devoted to representing the process of dealing with the lived experience of mental illness, which, the game correctly asserts, is not always a straightforward process. Madeline has her literal ups and downs as she climbs the mountain and her journey is thwarted by a “dark” version of herself conspiring to stop her.

That “dark” Madeline, or “Badeline”, obviously representing the anti-recovery impulse to give in to the despair of her depression, turns out to be nuanced as well. She begins the game as its villain, chasing Madeline and stalking her by hiding in her own reflection (I would love to get more into the psychoanalytic significance of mirrors in the game, but it’s too tangential to explore here). By the end of the game, however, Madeline realizes that she must, in fact, work together with Badeline if she wants to reach the top of the mountain, helping to drive home the game’s message that mental illness is not always something that is “conquered” so much as it becomes a part of ourselves that we can learn to live in peace with.

I was even more impressed by the careful handling of the game’s minor characters. The ghostly hotel concierge Oshiro could easily have been painted as a “bad example” foil to Madeline, the kind of person who deals with depression in the “bad way” because he never made it all the way up the mountain; instead, he is as nuanced as anything else in the game. On the one hand, his story is a cautionary tale about the potential for two depressed people to weigh each other down with their illness; on the other, he is a sympathetic character who only becomes truly monstrous by virtue of Badeline’s meddling. This implies that it’s not Oshiro himself who is the problem, but the thought traps of depression that corrupt our relations to others.

If there’s any fault in Celeste, it might be that its simple-yet-challenging and rewarding gameplay is a little too fun to be a realistic metaphor; this renders its relationship to the actual experience of dealing with depression less accurate. Still, there’s so much this game does right in tackling its difficult subject that it’s hard to fault it for not getting everything perfect. Along with Psychonauts and Persona 5, it allows us a glimpse into a world of video games that don’t paint those living with mental illness as monsters, opting instead to depict nuanced, three-dimensional portraits of their struggles.

———

Kurt Grunsky is a library worker and writer based in Toronto. His writing focuses primarily on pop music and video game analysis.