Barry Windsor-Smith’s Taxonomy of Monsters

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #156. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Wide but shallow.

———

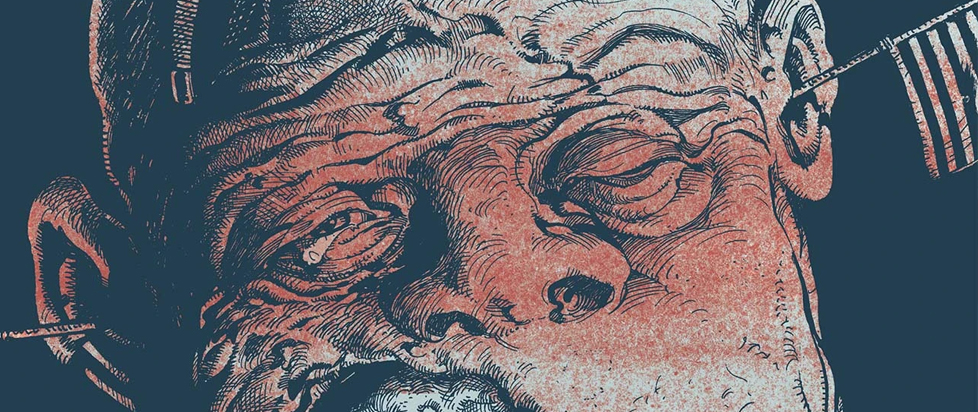

This is not a tome full of the fun monsters. Here we have a lavishly inked non-stop thread of the grotesque, the domestic and the systemic selection of monsters. A graphic novel so confident from page to page that there are no omniscient explanations, no breaks, no titles, no section breaks to speak of. The first few pages lay out exactly what’s going on with Monsters: a boy is beaten half-blind in a shed by an adult man shouting in black letter gothic German, the boy’s mom saves him, if you can call it that. The monsters are given shape, indisputably outlined.

But Barry Windsor-Smith is a veteran of superhero comics, and as such, knows that you can’t title a book Monsters without a menagerie of such. You don’t need a slice of Windsor-Smith’s bibliography on your shelf to immediately appreciate what’s going on with this opus, a book that reportedly took him 35 years to complete. I didn’t, and even to my average eye it was clear that this was the work of someone absolutely in charge of their craft. Oversized compared to the usual comic or graphic novel formats, each page rings with meticulously placed ink to vary from intimate conversations through action scenes and malignant science and back around again and again, cycling through time and the astral world to wind every loop back together.

Windsor-Smith plays with the assumptions we’ve cultivated over years of comic book publishing—a father psychologically ground up by war literally cursed by that pain to distribute it to his family almost immediately upon his return; a Nazi scientist so comically evil we almost forget that we first meet him as a member of the US Army, not in disguise but someone the forces embraced and promoted and granted a black budget based solely on what he promised he could deliver; the hulking metastasized boy vat-grown into a terrifying mass; and the unknown monstrous in Elias’s familial powers of telepathy and communication with the dead. Each of these tropes has played through half-tone pages over the decades, themselves metaphors for what we fear about ourselves and the universe in which we live and understand so little about.

All of this is upfront, clear, and understood. It’s also likely the least engaging aspect of Monsters – rather, beyond the impeccable artistic accomplishment from page to page, we are treated to the admirable attempts of humanity to face its monsters. More often than not we fail in these confrontations, often not for a lack of moral fortitude or desire to overcome such evil. It’s that monsters are often born from our sense of being overwhelmed and losing control with nowhere to turn. This is where systems fail, or worse, were built to exploit such moments of need and fear. Whether it’s an army full of soldiers explicitly trained to follow orders from a clear sociopath such as Roth, stomping around with a leadership style built on the foundational text of toxic masculinity, or a housewife determined to appease a broken husband until it’s too late, so brainwashed by an indifferent society so as to never even consider escaping the domestic violence let along being deposited right back into the hellscape by law.

Why read a graphic novel like this? Let alone award it an Eisner, one of the highest possible acclaims available to comics? Beyond the illustration and flow, which honestly stands among the defining work of Eisner himself, it’s that the book refuses complicity with the destructive unknown, even at personal cost to characters like Elias. The soldier sacrifices himself to set right events put into place when he wasn’t much more than a toddler himself, devastating his family. Maybe such a sacrifice is monstrous in itself – I’m sure his wife Bess thinks so, despite Elias’s efforts to help her understand. But she cannot know, and dare not believe what he tells her about his abilities, themselves not enough to save him.

Elias breaks the cycle established within Monsters. His kids will likely be OK despite the hardships he leaves them to suffer with, but he sees his role within the machine that chewed up Bobby Bailey and spit out a tower of destructive misunderstood flesh, and uses his gifts to bring Bobby some peace. Because at the end of any good comic book, no matter how nebulous, we must be left with a sense that the monstrous has been exorcised.

———

Levi Rubeck is a critic and poet currently living in the Boston area. Check his links at levirubeck.com.