The More the Merrier: Two Robin Hoods from Hammer Films

The story of Robin Hood is one that we all know, even if we don’t know where we know it from. What’s more, it’s one that – as with King Arthur or the myths of Greek antiquity – we’re sure has a correct version, even though it is actually composited from a wide array of sources that often don’t agree with one another.

By the time I was a kid, the story of Robin Hood had already been brought to the screen many, many, many times… so many, in fact, that the Robin Hood films with which I grew up were all parodies, pastiches, or deconstructions. To wit, the earliest Robin Hood films I remember seeing were Disney’s animated version from 1973 – which made furries and bisexuals out of a whole generation – as well as the Kevin Costner film from 1991 and Mel Brooks’ spoof Robin Hood: Men in Tights, which hit screens just two years later.

One thing that was clear from those three films, even when I was a kid, was that they were all drawing from a deep well of previous cinematic adaptations. Characters and situations were intended to be recognizable, even if you’d never actually seen the films that made them famous. And rightfully so. I knew the gist of the Robin Hood story and its major players; knew what I was supposed to expect, and when those expectations were being skewered or thwarted, even though I had never seen any of the myriad prior adventures of the rogue from Sherwood Forest.

The most famous and legendary of these is, undoubtedly, The Adventures of Robin Hood from 1938 – a Technicolor spectacle starring Errol Flynn and directed by Michael Curtiz. But even it was not the first. Alan Hale Sr., who plays Little John in The Adventures of Robin Hood, had previously essayed the same role in the 1922 Robin Hood, starring Douglas Fairbanks. Which, incidentally, was the most expensive movie of the 1920s – no small feat – reminding us that Robin Hood pictures were once big business.

Such was the case at Hammer, where Val Guest’s Men of Sherwood Forest was not only their first stab at the Robin Hood myth, but also their first film shot in Eastmancolor – though it sadly isn’t included in this new, Region B set from Indicator. For good or ill, however, Hammer’s plans to capitalize on period dramas and swashbuckling adventures like Robin Hood were put on hold the following year, when the success of their adaptation of Nigel Kneale’s The Quatermass Xperiment pointed the studio in a new direction, one that would shortly lead to the preeminence of their cycle of gothic horror pictures.

“Graves have been known to be empty…” – Sword of Sherwood Forest (1960)

So, it was more than half-a-decade before Hammer would return to Sherwood Forest. By then, the British Board of Film Censors was taking a hard look at horror films, even those to which it awarded an “X” certificate, especially in the wake of the controversy surrounding Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, released the same year as Sword of Sherwood Forest.

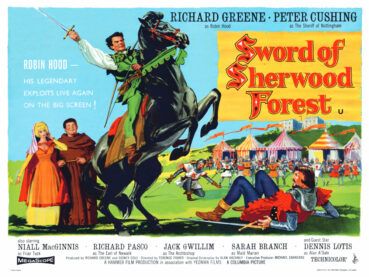

By that time, a popular TV series – called The Adventures of Robin Hood, again – had been running for several years on Britain’s ITV network. Launched just a year after Hammer’s Men of Sherwood Forest, the series starred Richard Greene as Robin Hood and ran from 1955 until 1959. Which meant that, when Hammer was ready to go back to the well, it only made sense that Greene would reprise his television role, which he did in Sword of Sherwood Forest, a film he also co-produced.

Though this makes it seem a bit like a movie-length adaptation of the series, Greene is surrounded by plenty of talent – most notably, at least for Hammer horror fans, Peter Cushing, who steals the show as the villainous Sheriff of Nottingham. Naturally, Cushing is ideal for the part, and, though I haven’t seen many of the previous incarnations, it’s difficult not to see his performance reflected in many of the ones that have come since. He is also perhaps too good a fencer, compared to the people around him. There’s only one real sword fight between the Sheriff and Robin, but it’s clear that Cushing is struggling not to hilariously outmatch his opponent.

Of course, Cushing and Greene aren’t alone. The cast of Sword of Sherwood Forest is impressive, indeed, including at least three future alumni of Jason and the Argonauts. None other than Niall MacGinnis (Karswell from Night of the Demon) plays Friar Tuck, Jack Gwillim plays the Archbishop of Canterbury, Nigel Green is Little John, and an uncredited Oliver Reed even shows up as a sleazy noble.

Is the finished product up to that pedigree? It most certainly is not, but it fits neatly into both the history of Robin Hood movies and the history of Hammer Film Productions, kick-starting, as it did, their push into more family-friendly, swashbuckling fare (alongside their gothic horror output) in the ‘60s, where it would be followed by such films as The Pirates of Blood River, Night Creatures, The Brigand of Kandahar, and, ultimately, A Challenge for Robin Hood, their final foray into Sherwood Forest, and the other movie in this two-disc set from Indicator.

“All will find their freedom here, where we wear the Lincoln green.” – A Challenge for Robin Hood (1967)

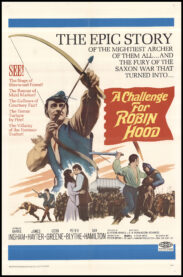

Seven years after Sword of Sherwood Forest, Hammer’s dalliance with swashbuckling adventure stories (largely) ended where it began – with Robin Hood. This time, Robin is played by Barrie Ingham, while the Sheriff is played by John Arnatt, Maid Marion is Gay Hamilton (though there’s a subplot switcheroo suggesting for part of the film’s running time that she’s actually played by Jenny Till, who appeared in Masque of the Red Death a few years before), and Peter Blythe plays Robin’s scheming cousin, who is largely added to the plot for the purposes of the movie. If none of those names are quite as familiar, it’s because this outing is considerably less star-studded than the previous one.

Also, as you may have gathered from the “scheming cousin,” above, this is the first of the Hammer films to offer Robin an origin story, borrowing from some of the (many and varied) literary sources, which eventually situated Robin’s rebellion amid tensions between Norman and Saxon nobles in England. As such, this feels like a sort of mid-point between some of the earlier cinematic takes and the later, more “historically accurate” films we would get in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

In spite of a whole host of reasons why this should be a lesser outing, it’s actually quite a bit better than its predecessor. The origin story – which departs considerably from the “Robin of Loxley” version we’re accustomed to from films like Costner’s Robin Hood, while still positioning Robin as nobility – mostly works, and presents a more tightly-imagined narrative arc than is usual for a Robin Hood picture. And the action scenes this time around are much better.

Though this is a somewhat more serious-minded Robin Hood than Sword of Sherwood Forest, there are still plenty of comedic elements, which work more often than they don’t – even when they’re dipping into the absurd, as when the Sheriff’s men are, at one point, foiled by a pie fight breaking out. High points include a wrestling match between this movie’s version of Little John and Robin Hood as “The Masked Monk.”

Speaking of the Sheriff, John Arnatt has his work cut out for him to follow up Peter Cushing’s performance, but he does so admirably. Arnatt’s Sheriff is much more fey, and seems to be having a great time, even when his side is losing. All he needs, as my spouse pointed out, is a bucket of popcorn at any given moment.

Ironically enough, while A Challenge for Robin Hood proved to not only effectively be Hammer’s final Robin Hood film but also the closing chapter of a certain era of the legendary British studio, it ends on a note that seems to suggest a sequel in the works, as the Sheriff escapes to cause mischief another day. A heavy contrast to Cushing’s Sheriff, who is dispatched rather nonchalantly by treachery among his own allies, rather than in a skirmish with Robin Hood.

While Hammer would continue to incorporate elements of swashbuckling adventure into horror pictures like Captain Kronos – Vampire Hunter or The Legend of the Seven Golden Vampires (both 1974), A Challenge for Robin Hood was the last time the venerable production company would dabble in this sort of film, not counting the 1973 release of Wolfshead: The Legend of Robin Hood, a failed TV pilot cum theatrical feature directed by John Hough (The Legend of Hell House).