The Sixties That Weren’t, or, How Psychonauts 2 Forgets Politics

This is an excerpt from a feature story from Unwinnable Monthly #146. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

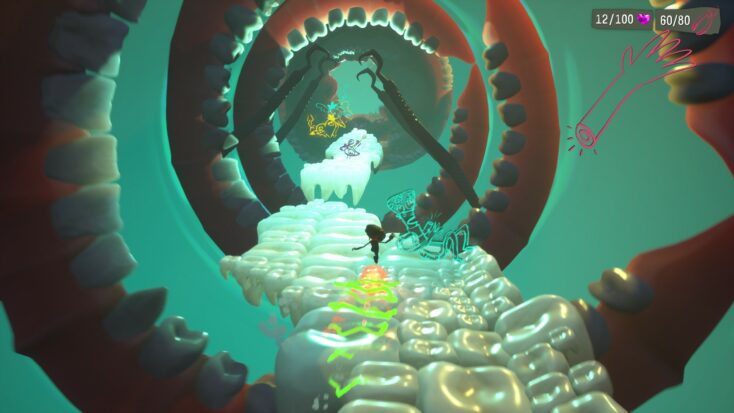

Psychonauts 2 is a trip. Its basic premise invites psychedelia. Playing as the protagonist Raz, an intern for the Psychonauts agency, you dive into the minds of different characters, each of which is represented as a quirky platforming level. These levels turn the fantasies, anxieties, obsessions and traumatic memories of a psyche into architecture and terrain, as if the brain were a playground, our hidden shames, buried losses and secret pleasures so much exotic equipment over which to vault. Sometimes, the trip through the mind is simple. The game’s tutorial level features tunnels studded with incisors and molars, a dental nightmare that encapsulates the mind of Dr. Loboto. There are light puzzles to solve, but they are but momentary delays along a linear path to uncover Loboto’s secrets. The mission is a failure. Yet, as any good tutorial level should do, the cavern of toothy terror sets the scene. The mind is more than a terrible thing to waste, it’s a theater of operations, a target of intervention – a thing to change.

The psychedelic imagery of Psychonauts 2 wouldn’t have been possible without the cultural scene of the 1960s. It’s not just that the game’s color palette and character costumes borrow so heavily from the hippies and the mods that you’ll be tempted to shine a blacklight on your screen. The game also cribs from the politics of the sixties, specifically, from the period’s commitment to consciousness-raising, system-wide social transformation and experiments with communal life. The game’s psychedelic romp from level to level echoes the efforts of 1960s social movements to change the texture of everyday life. The Black Power Movement didn’t want a Black president. It wanted to purge society of racism and class domination. Women’s Liberation wanted more than equal pay. It wanted genders and sexualities free of heteronormative expectations; it wanted family structures liberated from domineering daddies. Change was supposed to happen from the bottom up and inside out. To quote philosopher and activist Michel Foucault, the goal is “not to discover what we are but to refuse what we are. We have to promote new forms of subjectivity through the refusal of this kind of individuality which has been imposed on us for several centuries.”

Psychonauts hack minds to change lives. The psychic powers of Raz and the other agents literalize the expansion of consciousness promised by LSD gurus like Timothy Leary and Ken Kesey. The game’s design is a set of discrete levels connected by a hub world (the Motherlobe), each level a messed up psyche waiting to be fixed. The world of Psychonauts 2 will be made right as long as you clear out some enemies and hop your way from the entry point to the exit point of each level. In short, the systemic change imagined by the new social movements of the sixties gives way to a series of therapeutic challenges. Which isn’t to suggest the franchise lacks creativity. To the contrary, Double Fine proves itself plenty willing to experiment. One level is a cooking show – think the Food Network’s Chopped – in which you somersault ingredients from one cooking station to another, while a clock counts down to failure. Another level portrays a character’s struggle with alcoholism as a water-drowned planet, its islands home to giant glass bottles that seal away painful memories. Metaphorical extrapolation turns personal pathologies into little virtual worlds, so that as Raz overcomes obstacles and enemies, he’s not so much trouncing bad guys as healing a friend. Not revolution, then, but therapy.

If the sixties-ness of Psychonauts 2 isn’t immediately obvious, the “PSI-King’s Sensorium” level tips the game’s hand with respect to its historical and cultural influences. In this level, you reconstruct Helmut Fullbear’s shattered mind by taking a magical mystery tour through the five senses. The game represents these senses as members of a rock band, your task being to recover each of them in an effort to get the band back together. The level sees you touring a simple overworld map in a Volkswagen Bus, stopping at different locations or sub-levels, each of which represents one of the senses (taste, for example, features tongue platforms that wiggle in a perturbing fashion). The artists at Double Fine cite the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine as an important influence, and it’s an obvious one. The “Sensorium” features bright colors, psychedelic imagery (floating eyes, giant mushrooms, rainbow bridges), sitar music and an animation style reminiscent of the Beatles’ film. The level culminates on stage, as Helmut Fullbear returns to Viking-guru-rockstar form to perform the song “Cosmic I/Smell the Universe” (a playful nod to the Beatles’ “Across the Universe”): “But now I sense / A reason to this rhyme / And I can smell the universe / And I can taste the sky / And I can see each molecule / Through my Cosmic I.”

“Psi-King Sensorium” is just one level among others, a distinct one in terms of its art and music. Yet the level reveals something about the game as a whole, namely, that its vision of change involves healing fractured psyches, curing individual rather than social ills. Change doesn’t imply something new but a return to a preexisting wholeness – the restoration of the good old days. This wouldn’t be so remarkable were it not for the way the game riffs on the sixties, borrowing the decade’s promise of liberation. In Psychonauts 2, liberation doesn’t mean revolting against the status quo but getting over the traumas that haunt your psyche.

———

Christian Haines is an English professor at Penn State University and a managing editor at Gamers with Glasses. He’s the author of the book A Desire Called America: Biopolitics, Utopia, and the Literary Commons (Fordham, 2019).

You’ve been reading an excerpt from Unwinnable Monthly Issue 146.

To read the article in its entirety, please purchase the issue from the shop or sign up for a subscription to Unwinnable Monthly!