The Summers Wind

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #144. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

A tongue-in-cheek but also painfully earnest look at pop culture and anything else that deserves to be ridiculed while at the same time regarded with the utmost respect. It is written by Matt Marrone and emailed to Stu Horvath and David Shimomura, who adds any typos or factual errors that might appear within.

———

How many years since he thought of that automobile graveyard? The door to the past is open. He could push it shut, latch and lock it, but he doesn’t want to. Let the wind blow in. It’s cold but it’s fresh, and the room he’s been living in is stuffy.

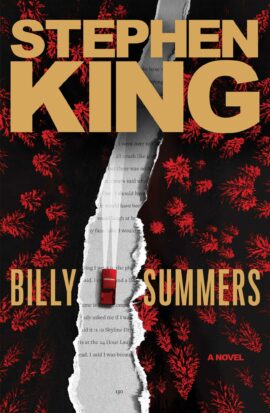

I’ve probably read more books by Stephen King than any other author, but I don’t think of him as the world’s greatest writer. I think of him as a genius storyteller. But those five wonderfully evocative sentences, which I just came across in his latest novel, “Billy Summers,” took me right out of the story, made me dog-ear the page, put the book down and start typing.

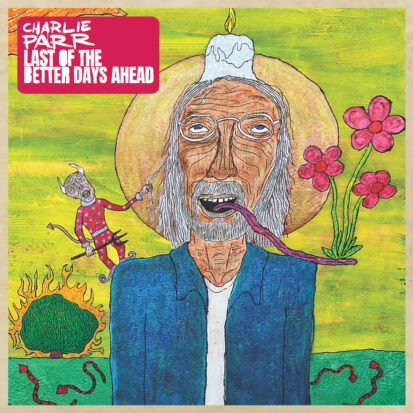

King’s words brought to mind the new record from another genius storyteller, Charlie Parr. Parr also uses junky old automobiles – well, one in particular – as a jumping-off point into the past, on his new album’s exquisitely named title track, “Last of the Better Days Ahead”:

Money can’t buy back that ʼ64 Falcon that you sold in your 20s and then regretted it was gone // because you thought it contained some meaning or some answers to a life that you never bothered to question // or even take a good close look at.

The main character in Parr’s song, identified as being in his 50s, is on a sort of desperate, mid-life crisis road trip back to his hometown, where he once “was handed all [he] needed without cost.” As he wrestles with the emptiness he feels, he is faced with how much he’s taken for granted. Even if he could drive that old car again, though, what he’s lost was never about anything tangible to begin with.

The song ends as his engine dies near a soybean field, leaving him stranded with nothing to do but watch the sunset as it turns the sky to rust.

As I sit here on my front porch rocking chair on a beautiful late summer afternoon, Stephen King book on my lap, writing out scattered thoughts as I watch people walk by below me on the street, I’m struck not by how similar King’s sentences are to Parr’s lyrics, but in how they seem to approach unlocking the past from completely opposite directions.

Nostalgia, in the Parr song, can be painful – a gut-punch trip from the stuffy room you’re living in back to a past you never could have truly appreciated at the time, and now have no choice but to acknowledge is gone forever. The past, taken within the larger context of Billy Summers’ journey, can mean exploring even the most intense trauma as a form of healing instead of brooding over regret or loss.

I’m several years away from my 50s, and maybe my struggles with the past will be even worse then, if and when I get there. I suspect they will. After all, that’s only more time for the things I try not to take for granted to fade away. My time with my parents, or watching my kids experience so much for the first time. I haven’t felt Billy Summers’ trauma but enjoying King’s breath of fresh air is difficult.

Because I am outside now on such a perfect day, and I’m not stuck in a stuffy room, figuratively or otherwise, I can feel that nice breeze from the past. I know sometime later tonight or another to come, the sky will turn to rust and I’ll long for what’s gone, less like Billy Summers coming to terms with himself and more like Parr’s lost, sentimental wreck – whether it’s running around my old apartment complex as a four-year-old, playing baseball with my friends, or the fresh grass and peanut smell of my grandparents’ backyard. I’d throw balls against their stoop or eat my grandma’s pancakes that are now my job to make on special occasions. We stopped by that house the other day – just for a moment to pick up something from my uncle – and my two sons asked me, from the back of the car, where we were. Both said they’d never been there before, and, even though that isn’t technically true for my six-year-old, it might as well be. I told them a bit about my grandmother’s garden and how much my grandfather would have loved them if he’d been able to meet them and just how lucky I was to have them both as grandparents for the time that I did. And how lucky they are now to have the grandparents they have. They know it, but only as much they can at their age. They changed the subject almost immediately.

A few weeks later, I asked my oldest son how crazy does it feel that he’s going to start first grade in the fall. He told me it wasn’t crazy at all. He’s alive. What else is there to do but the next thing?

I haven’t stopped thinking about his answer since, though it’s already ancient history. By the time this is published, he’ll have been a first-grader for nearly two months.

The door to the past is open. I could push it shut, latch and lock it, but I don’t want to. Not on this beautiful day, sitting on this porch, reading this book. I’ll want to close it off later, I know, though doing that gets harder all the time. The next storm, I suspect, might blow it right off its hinges.

———

Matt Marrone is a senior MLB editor at ESPN.com. He has been Unwinnable’s reigning Rookie of the Year since 2011. You can follow him on Twitter @thebigm.