Hostile Architecture

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #142. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Architecture and games.

———

Walk around any big city these days and you’ll find some buildings that have strange design features. The best example would be a spiked staircase or a sloping window sill, but you might also come across a badly placed bicycle rack or a particularly tall barrier. What you’re seeing is in fact a targeted attack. The point is to prevent houseless people from sitting, sleeping or even just spending time in these places. This amounts to what you call hostile architecture. Structures like these are more about producing pain than providing shelter.

The purpose of hostile architecture is to make sure that buildings are used as intended. This doesn’t sound like a bad thing, but the results definitely speak for themselves. People without homes literally get left out in the cold because the places where they would otherwise be able to find refuge from the elements have been rendered completely inaccessible. What else can you call this apart from a waste of space? Buildings are supposed to accommodate their occupants, but structures like these might as well be fighting some of the most vulnerable people out there. I’m pretty sure that you could talk about this kind of thing in terms of design crimes.

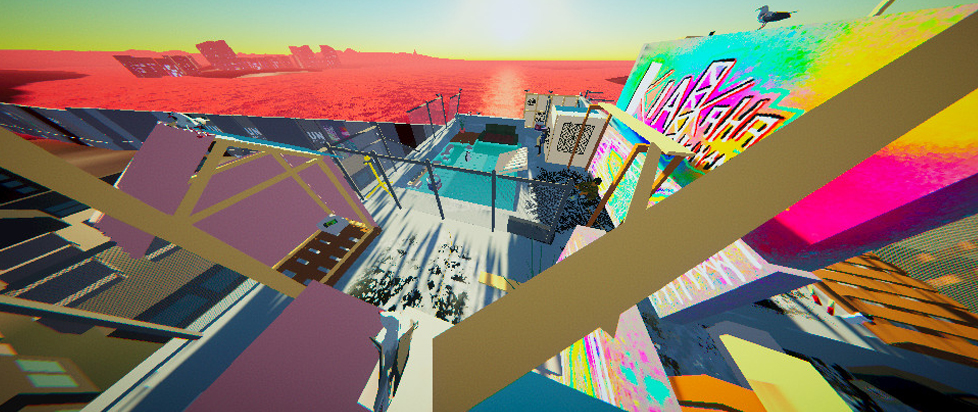

The developer behind Umurangi Generation, Origame, tries to imagine what the future would look like if hostile architecture were the norm instead of the increasingly common exception. You can see this by exploring the levels known as Kati Kati, Strand and Metro. You really have to explore these levels because quite a few parts of them can’t be accessed without sneaking around something. This, of course, plays into the mechanics, but it provides an interesting perspective on hostile architecture, too. Since you aren’t directly targeted by it unless you’re a person experiencing homelessness, most of us end up ignoring hostile architecture in our daily lives, but Umurangi Generation forces you to experience what it feels like to be the victim of a design crime.

Hostile architecture is all about inaccessibility. The idea is to have certain areas of a structure that for all intents and purposes can’t be occupied by anybody. The best example is putting spikes on a ledge so that you can’t sit on it without getting a hole in your pants, but there are much less painful methods of making sure that you stay standing. Building a wall is of course the oldest trick in the book. You can see this at work in Kati Kati. The level is basically just a whole bunch of concrete walls and chain link fences with a series of structures in between them. You have to climb up the fire escapes of these structures and jump down onto shipping containers, cardboard boxes and wooden planks in order to get around all of these impediments to your movement. The only time that you’re not climbing over something is when you’re crouching down below it. You’re constantly weaving and winding your way around the level.

The best architecture is empathetic. I don’t mean that buildings can feel emotion, though. I mean that structures are designed to meet the needs of their occupants. The classic example of empathetic architecture is putting an awning in front of a door so that you don’t get wet if you have to wait outside in the rain. The architecture in the Strand is clearly supposed to be lacking empathy. The level consists of an intersection with a bunch of buildings on each corner. The closest thing to an awning that you’ll find is a fire escape. These don’t even have railings to keep you from falling down them. You’ve also got the signage. The bright lights might seem exciting at first, but when you stop to think about them, they’d be a real bother for anybody trying to sleep either inside a building or outside on the street. Similar to the situation in Kati Kati, the Strand also happens to be filled with walls that prevent you from easily getting around the place.

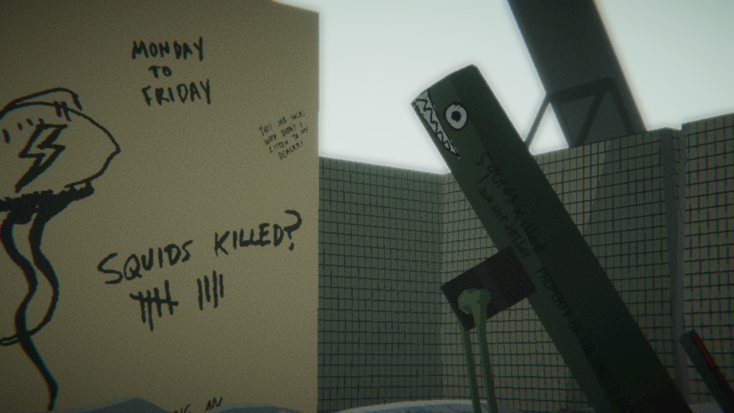

The purpose of a bridge is to facilitate movement. You go from point to point instead of making your way around some sort of inconvenient feature like a body of water. Bridges on the other hand work a little bit differently in the Metro. This would make for an extremely frustrating subway station when it comes to conveniences. The bridge stretches across the railway tracks, but a couple of areas are blocked off with metal barriers. The result is that you have to creep along a bunch of catwalks to access most parts of the level. The bridge only gets you from where you are to where you’re otherwise allowed to be. This isn’t necessarily the spot where you’re trying to position yourself, though. You have to jump on top of the train cars for example just to get over to the area with all of the shipping containers. You get the impression that you’re being fought by the Metro as you go about your business.

You can see hostile architecture at work in Umurangi Generation. The point is to complement the mechanics, but the game still reflects on hostile architecture by forcing you to actually confront these design crimes. You can’t just ignore them and get on with your life. You become a victim just like all of the homeless people in the world around you.

Why does it matter that Umurangi Generation makes you experience hostile architecture? The answer is that we have the power to make livable cities. We can do better than hostile architecture. The fact of the matter is that structures need to have spaces where people can take refuge in times of need. Nobody should have to search for somewhere to sit down when they’re tired. Nobody should have to head outside when they’re trying to stay warm. Basic needs like these can easily be accommodated by decent design. I’m using this particular term because any other kind of design is frankly indecent. I would even go so far as to call it a crime. We haven’t yet reached the point of no return, so the intrusion of hostile architecture into our cities can still be stopped, but we have to do everything in our power to fight back. We need to call out hostile architecture whenever we come across it. Remove spikes. Flatten window sills. Put bike racks where they belong. Tear down tall barriers. We need to make sure that our cities can be occupied by everyone regardless of their social status.

———

Justin Reeve is an archaeologist specializing in architecture, urbanism and spatial theory, but he can frequently be found writing about videogames, too. You can follow him on Twitter @JustinAndyReeve.