Variations

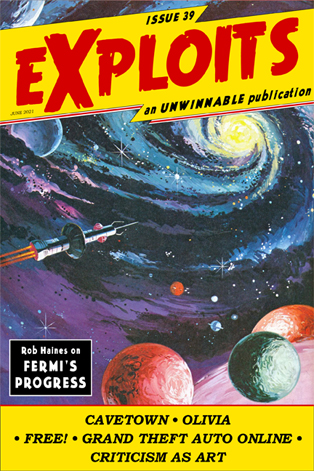

This is a reprint of the Music essay from Issue #39 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

This is a reprint of the Music essay from Issue #39 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

———

“This being human is a guest house. Every morning a new arrival.”

–Rumi

Glenn Gould’s “Goldberg Variations.” Yo-Yo Ma’s “Cello Suite no. 1 in G Major.” Regina Spektor’s “Samson.” Among these prolific artists, individual songs have come to define their discographies. Gould popularized the 18th century composition with his 1955 recording of Bach’s work. He was 22. Then, in 1981, he recorded the variations again, creating a record nearly 20 minutes longer than before. 26 years apart, the variations bookmarked Gould’s career and have defined the legacy of the pianist. He died the following year at 50.

Yo-Yo Ma learned to play the cello with the Bach composition “Cello Suite no. 1 in G Major” and recorded it for the first time in 1983. On the eve of 2018’s Six Evolutions, the cellist claimed that the album would feature his final performance of the piece, speaking of the original recording with a similar retrospection to Gould.

And unless you’re a devoted fan of the Russian-American singer, songwriter and pianist Regina Spektor, you may not have known that one of her most famous works, the haunting “Samson,” is her second recording of the song. The original, recorded in one take on Christmas Day five years earlier, is only distributed through CDs sold at her concerts (and YouTube, of course).

Revision is an inherent part of music, and each performance could be understood as a slight variation on the past. A slow transformation is almost unavoidable over the course of a life as an artist develops their skill with their instruments, learns and interprets a composition in new ways and grows and changes as a person. What these recordings offer in their canonization of different variations is a juxtaposition that glimpses lives and careers.

When Cavetown released their debut single “This is Home” in 2015, they had already amassed a following from their covers and original songs uploaded to YouTube and Bandcamp. At 16, they were the tail end of a generation of musicians that found success performing on the platform from their bedroom. He released his first album, a self-titled LP, independently in 2015 and to this day the production of Cavetown’s music is mostly a solo endeavor.

When Cavetown released their debut single “This is Home” in 2015, they had already amassed a following from their covers and original songs uploaded to YouTube and Bandcamp. At 16, they were the tail end of a generation of musicians that found success performing on the platform from their bedroom. He released his first album, a self-titled LP, independently in 2015 and to this day the production of Cavetown’s music is mostly a solo endeavor.

I first discovered Cavetown’s discography some years after, probably around the release of Lemon Boy in 2018, when I was in college. Though the artist’s recurring themes of dysphoria, suicide, anxiety and boyhood have drawn trans listeners around world, it’s hard to call transness a defining trait of his music and I’ve purposely avoided speculating on the orientation of their relationship with masculinity because of that. They only “came out” as trans last year, confirming what seemed apparent to many listeners but leaving other questions open. Their discography is comprised of songs that have become unofficial trans anthems (notably “This is Home,” “Lemon Boy” and “Dysphoric”) and more specifically speak to trans masculine experiences (cutting his hair and hiding his chest). Yet while I speak of them with some remove from the music they make so as to not speculate or impose an identity on the songwriter (I have yet to mention the artist’s actual name for this reason), it’s clear in songs like “Boys Will Be Bugs” that Cavetown is consciously constructing boyhood in a world that defines both transness and masculinity in terms of pain.

This made their music approachable – comforting even – when, in 2019, I resumed questioning my own relationship to masculinity and listened to Cavetown on repeat. I had been out and trying to embrace femininity for a couple of years and almost suddenly felt my expression change. It was while listening to “Juliet” on repeat that summer, thinking constantly of the lyrics “I wanna make a color that no one else has seen before,” that I first thought of my gender as something more fluid and variable than I had ever considered before. That period of my life was about reclaiming masculinity, making it my own and having fun with it.

This brings us to “Home,” the 2019 single based on “This is Home.” Separated by only four years, the lyrics and structure remain the same, but the key is changed to accommodate their deeper voice. The opening ukulele is replaced by guitar and the following instrumentation fits alongside the artist’s contemporary tracks as the composition transforms the meaning that we are left with at the end of its longer four and half minutes. When the song swells, it’s bigger, and when it diminishes, it’s smaller, singing with a vigor lacking in the original’s solipsistic interrogation of themself. Our common paths through dysphoria, suicide and growing up aren’t straightforward, and the struggles the artist originally sang of are not mere memories, but “Home” is sung knowing that he’s made it through all these before.

At 22, Cavetown is the same age as Glenn Gould when he recorded Bach’s “Goldberg Variations” for the first time. His career, like Spektor’s after “Samson,” carries on. Today I am 23 and beginning to recognize home as a place we encounter differently throughout our lives, but I feel like a guest in my own house sometimes. Returning as a variation of myself, each encounter is its own arrival. In Cavetown’s discography I find someone who is grateful for whoever comes, who is able to welcome and entertain the crowd of sorrows that occupy a body like mine. I am reminded that it is no small thing to feel at home in this place.