Terry Pratchett’s Antidote to Copaganda

Since the Black Lives Matter protests surged after the murder of George Floyd last June, we’ve seen many critiques of “copaganda” and the role it plays in neutralizing and even justifying extra-judicial powers used by the police. CSI: Miami glorifies police breaking the law to catch criminals without evidence; Blue Bloods critiques any anti-police sentiment as anti-American; even Brooklyn 99 reframes cops as lovable goofballs, who wouldn’t hurt a fly. But we rarely look at literature as part of this picture of aggrandizing the police. Do the same problems exist? I’m particularly close to this, given that I once worked for the famous Harrogate International Crime Writing Festival, held in the hotel where Agatha Christie was discovered after faking her own death. In all the fun panels and author interviews, no one ever asked: how does the genre relate to the real world problems of police brutality and institutional racism?

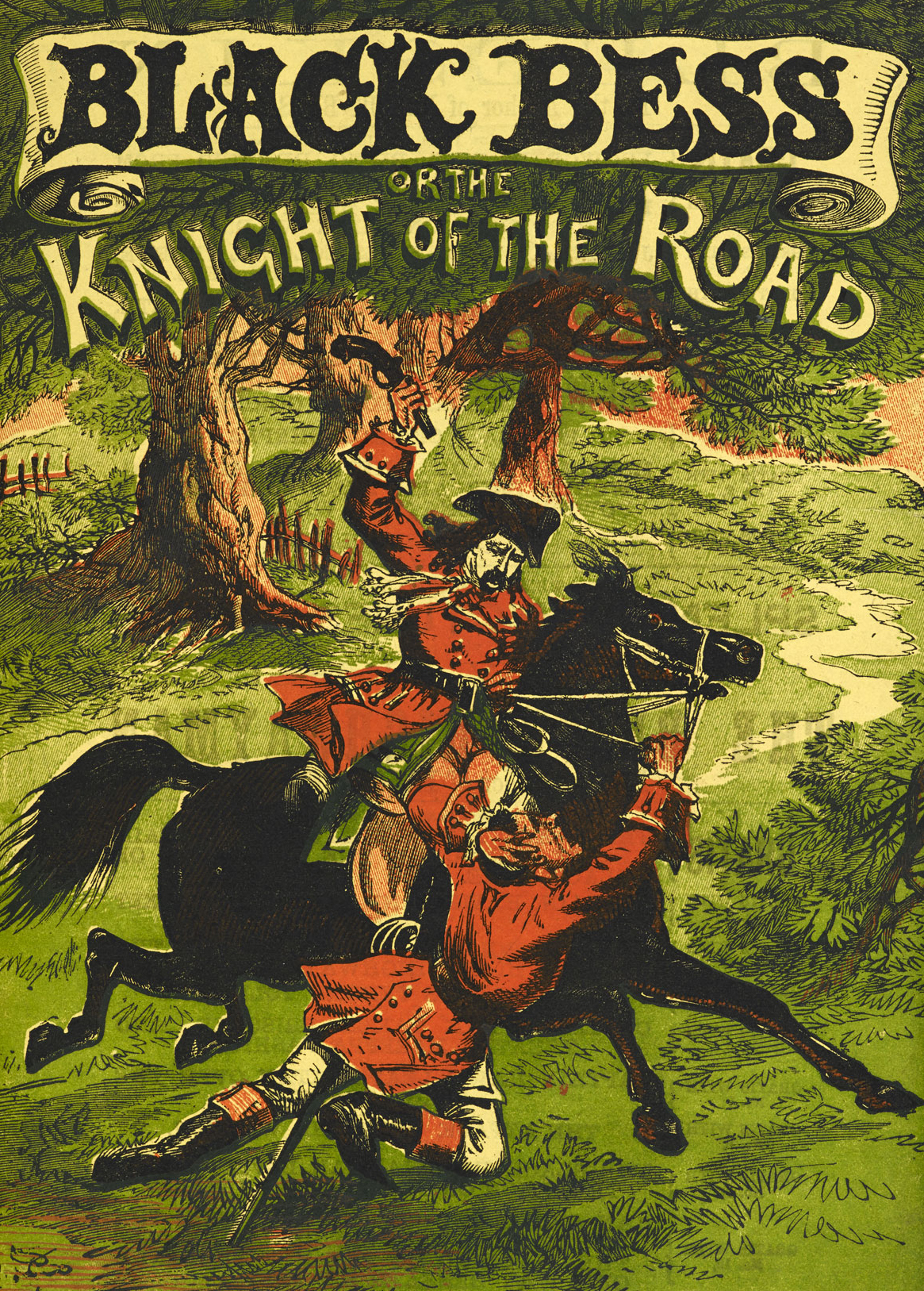

Crime literature seemed to start off well. Voltaire wrote the first prototype detective character in his novel, Zadig – so you know it’s high class. But America pioneered the first true detective novels – Edgar Allan Poe wrote “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” in 1841 and Louisa May Alcott, of Little Women fame, published her novel V.V., or Plots and Counterplots in 1865. Then came the pulp crime novel. Dick Turpin, a local anti-hero from my neighborhood in Yorkshire, was the subject of Black Bess: or The Knight of the Road, a retelling of the dastardly crimes of the dashing highwayman, reveling in the lurid depictions of violence. These cheaply produced novellas may have disappeared, but the tone and topic will be very familiar to podcast fans: dramatic and sensational retellings of true crime.

Then the crime novel hit its Golden Age – Hercule Poirot and Agatha Christie, Sergeant Cuff and Wilkie Collins, Lord Peter and Dorothy L. Sayers. Arthur Conan Doyle created the most famous fictional detective of all, and arguably Britain’s second most popular export (after colonialism): Sherlock Holmes. Holmes, with his focus on extrapolating and profiling criminals based on physical evidence, has even been credited with shaping the modern study and pursuit of forensics.

Then the crime novel hit its Golden Age – Hercule Poirot and Agatha Christie, Sergeant Cuff and Wilkie Collins, Lord Peter and Dorothy L. Sayers. Arthur Conan Doyle created the most famous fictional detective of all, and arguably Britain’s second most popular export (after colonialism): Sherlock Holmes. Holmes, with his focus on extrapolating and profiling criminals based on physical evidence, has even been credited with shaping the modern study and pursuit of forensics.

While many contemporary crime novels have a similar tone – and problems – as modern police procedurals, those early works in the Golden Age often had protagonists who openly questioned the machinery of justice. Christie’s Poirot sometimes chooses to allow perpetrators of crime to go free, knowing that a custodial sentence would not further justice. He, Lord Peter and Holmes frequently critique the work of police, who in their eagerness to close cases, often accuse and even convict the wrong person.

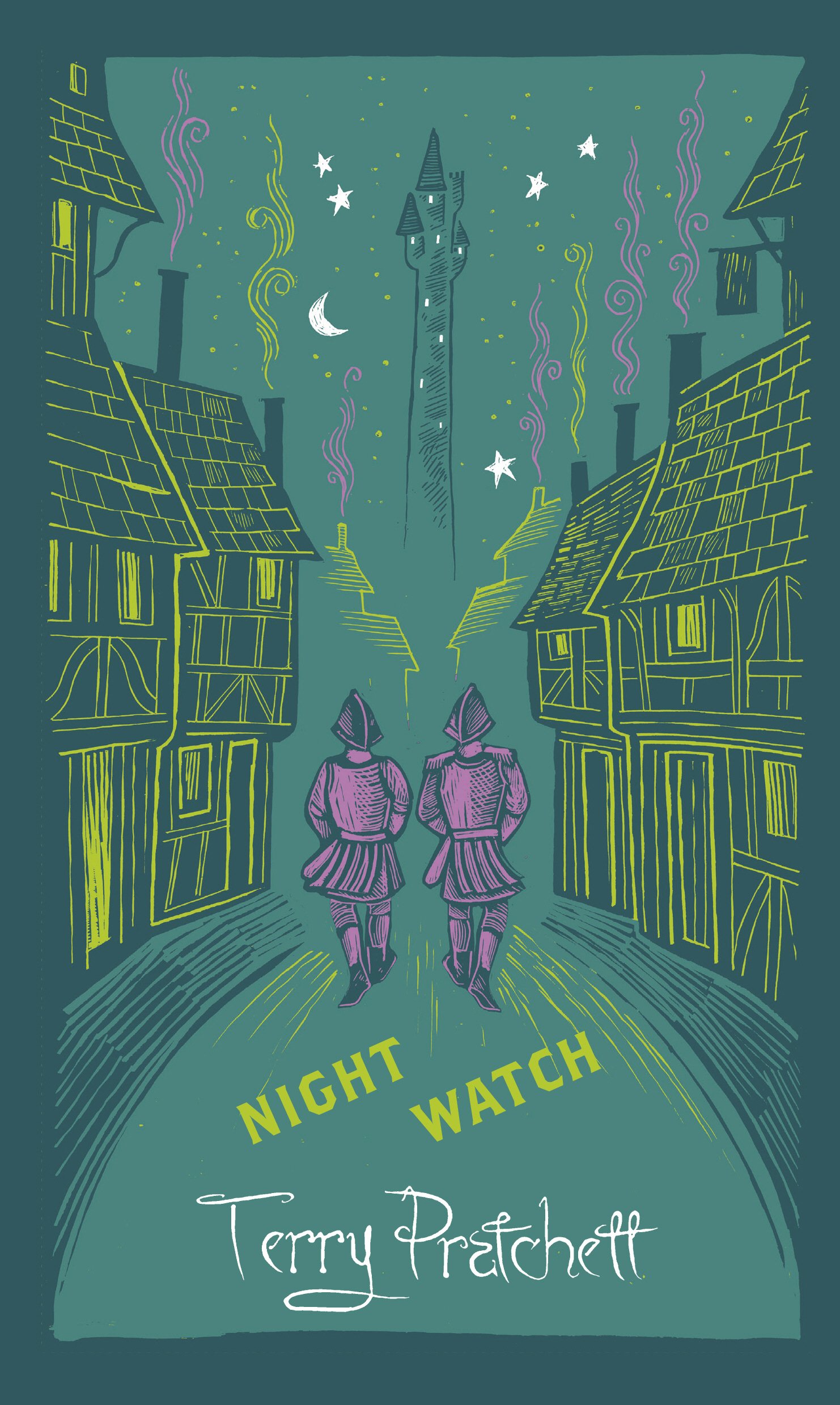

But for me, this critique is best explored in Terry Pratchett’s Guards series. These books are genre fiction within genre fiction – a gritty crime noir detective series set within a fantasy world – and they are some of my favorite books. In Thud, which explores racism, fake news and propaganda between magical races, Sam Vimes, our hero police officer, answers the age old question: “Who watches the watchman?” He defeats the enemy – the Summoning Dark, a malevolent magical entity, which spreads hate and fear – with what he calls the Guarding Dark: an inner police officer, who scrutinizes Vimes’s actions and holds him to the highest moral standards.

“‘I know that one,’ said Vimes. ‘Who watches the watchmen? Me.’”

As images of protests and police brutality were broadcast from America, Australia, Nigeria and the UK in 2020, I was compelled to reread Pratchett’s Night Watch. Here, Commander Sam Vimes has chased a criminal backwards through time and is thrown into the middle of a city in revolt. A corrupt and callous leader sits guarded in the Patrician’s Palace. Riots begin when a peaceful protest is broken up with force, killing several protesters. Those who speak out against injustice are disappeared from the street by secret policemen. While many of the watchmen across the city increase their violence and brutality to try and control the riots, violence only begets more violence.

In steps Sam Vimes. Instead of locking down the watch house and donning protective armor, he opens up the doors and sits on the front step, quietly sipping hot cocoa. His humor and non-violence deescalate the situation, and his neighborhood stays calm. The corrupt leaders insist the police begin to act more and more like the military and Vimes is eventually asked to fire on unarmed protestors. Instead he decides to join the revolt. He states clearly that the Watch serves the people and is there to “keep the peace.” He and his fellow watchmen turn against the army, the politicians and the elite to protect the ordinary folk from persecution.

In steps Sam Vimes. Instead of locking down the watch house and donning protective armor, he opens up the doors and sits on the front step, quietly sipping hot cocoa. His humor and non-violence deescalate the situation, and his neighborhood stays calm. The corrupt leaders insist the police begin to act more and more like the military and Vimes is eventually asked to fire on unarmed protestors. Instead he decides to join the revolt. He states clearly that the Watch serves the people and is there to “keep the peace.” He and his fellow watchmen turn against the army, the politicians and the elite to protect the ordinary folk from persecution.

Pratchett openly and frequently questions the purpose of police and justice through Vimes’s internal monologue. He questions why they can’t arrest the Patrician, the city’s leader, for ordering the deaths of civilians. He argues for the legalization and proto-unionisation of sex work. While Vimes’s “Free Republic of Treacle Mine Road” – a fantasy version of the DMZs we saw in cities across America in 2020 – cannot last, the novel asks the question: why aren’t the police on the side of ordinary people and keeping the peace? What would happen if they turned the light of justice on corrupt leaders? Why can’t we hope for “Truth, Justice, Freedom, Reasonably Priced Love and a Hard-Boiled Egg?”

The Guards series doesn’t shy away from the problems of the criminal justice system. It may be set in a fantasy world, but I feel it’s more realistic about the challenges to modern policing than any other media. There aren’t just “bad apple” watchmen screwing it up for the rest of them. Night Watch makes it clear that it’s the whole system – the law, the politics and the Watch itself – that is deeply flawed. Vimes’s entire career is dedicated to dragging the system into the light. Yes, the bad apples need to go, but the law needs to apply equally to everyone. Vimes grumbles about progressive hiring practices, but eventually views the unique skill set of each of the magical races as making the Watch stronger, as well as showing that the Watch is there to serve all of the people of Ankh-Morpork. Anti-racist practices, systematic reform and intolerance of corruption transform the Watch over the course of the Guards series. And this transformation isn’t portrayed as being easy, quick or a matter of good people vs. bad people. Everyone, including our hero Sam Vimes, has to work hard to remove bias from themselves.

Five long years since his death, Terry Pratchett is as relevant as ever. We’ve seen statements from writers of series like Brooklyn 99 where they admit that they are grappling with how to address the issue of police brutality in future series. The deeply exploitative Cops was cancelled, though there are rumors of it being reinstated. Perhaps showing the gritty and difficult work of reforming, as Pratchett does, provides a possible way forward for all media that focus on police work instead of just reiterating copaganda. Regardless, at this dark start of the new year, I recommend picking up Night Watch to return your faith in justice, and as a reminder that this too shall pass.