That’s a Recipe for Romance: The Norman J. Warren Collection

Not that long ago, I was hired to make a list of horror movies that take place on New Year’s – turns out there’s more of them than you’d think. In the process, I learned a little more about Bloody New Year, a film whose box art I recognized from my days haunting the aisles of video rental places but which I had never actually seen, having written it off as another in a long line of seasonal slashers, a subgenre I hadn’t yet learned to appreciate at the time.

What I uncovered in my research was enough to convince me that I needed to see Bloody New Year right away. So, a few months later, when I learned that Indicator was putting out a boxed set of films by cult director Norman J. Warren – including Bloody New Year – I figured this was the ideal time to check it out.

Prior to sitting down with the set, I hadn’t ever seen any of Warren’s films – not these, nor the earlier sex films on which he got his start. Besides that bit of research into Bloody New Year, I hadn’t read much about them. So, I didn’t really know what to expect, beyond what I could tell from lurid titles like Inseminoid and Satan’s Slave.

What I quickly came to learn was that all five of these films share several unmistakable qualities in common, even while they bounce around from one horror subgenre to the next – cashing in on whatever was popular at the moment they were made.

All of them are British. All of them are shot on shoestring budgets, and it shows. Most of them feature a surprising amount of full-frontal female nudity – possibly a holdover from Warren’s early days making softcore films. And all of them are more effective than their limited budgets and cash-grab premises should allow.

Because Bloody New Year was the movie that had initially attracted me to the collection, I decided to check it out first, even though it’s the most recent film in the set, which spans a decade beginning with Satan’s Slave in ’76, and to work my way backward from there.

Think About Time Like a River: Bloody New Year (1987)

Think About Time Like a River: Bloody New Year (1987)

According to IMDb, Bloody New Year is Norman J. Warren’s last feature film as director. Nevertheless, it seems like a good place to start in his oeuvre because, while it is definitely set in the ‘80s, it also feels like a creature out of time – just like its ghouls.

See, the premise of Bloody New Year kicks off simply enough: After stumbling into some trouble at a fun fair by the beach, our teen protagonists make their way to a nearby island where their boat capsizes and sinks.

Once on the island, they find a hotel that’s decorated for Christmas and New Year’s, even though it’s the beginning of July. Everything in the hotel is straight out of the 1950s, but nothing seems old or dusty. Then even weirder things start to happen.

Of course, those of us in the audience know that something is very wrong long before the kids do. After all, we’re aware that we’re watching a horror movie, while they still think they’re in a beach blanket bingo type scenario, pissed-off carnies notwithstanding. But we’ve also been treated to the black-and-white shots of a New Year’s Eve party in the hotel, ringing in the year 1960—a New Year’s Eve party where we know that something went terribly wrong.

In spite of the “killer POV” shots that start pretty much as soon as the kids get to the island, though, Bloody New Year is far from a typical slasher film. There’s certainly a body count, along with the kind of shot-on-video gore that you might expect. Arms get ripped or chopped off with some regularity. A guy’s head is demolished (offscreen) by a boat propeller. Hatchets chop into mannequin skulls and papier mâché heads explode. But for all that, Bloody New Year has more in common with an Italian spook show like Ghosthouse than it does Friday the 13th.

It doesn’t spend much time pretending otherwise, either. A figure that is (to the audience) clearly a ghost shows up by the 20-minute mark. But something more than “just” a haunting is going on here, too. A TV playing a 1950s talk show gives us the background, as much as we’ll ever get, anyway. It seems that, on New Year’s Eve in 1959, the government tested an experimental anti-radar device. One that had the power to bend light – and also time. The plane carrying the device crash landed on the island and the rest is history. Or isn’t, as the case may be.

This delightfully bizarre conceit keeps Bloody New Year – which was also released as Time Warp Terror – hopping. Even before our leads get to the island, there’s a chase through the fun fair that culminates on a ghost train. In the hotel, the kids watch the end of Fiend Without a Face before a home movie kicks on and a guy dressed as a sheik leaps out of the screen to attack them before folding himself up and disappearing into the lens of the projector!

There are attacks by film stock (a trick Warren had previously used almost a decade earlier in Terror); there’s quicksand and a seaweed monster that comes up out of the surface of the table; there’s an invisible plane crash and unseen laughter and Evil Dead-style camera swoops; there are bannisters that come to life and a blizzard indoors. And before all is said and done, there are plenty of sand-faced ghouls. Really, what more could you ask for?

Internal Disturbance: Inseminoid (1981)

Internal Disturbance: Inseminoid (1981)

Even after the extreme weirdness of Bloody New Year, there were plenty of surprises waiting for me in Inseminoid. The first was seeing Run Run Shaw’s name in the credits – according to IMDb, he “presents” the film, whatever that means.

The next was that Inseminoid is way less sordid than its sleaze-o-rama title would imply. It isn’t even the most graphic movie in this set. (Horrorplanet, its alternate title, isn’t a whole lot more representative, though I want to borrow it for an album title from some imaginary horror-themed metal band.)

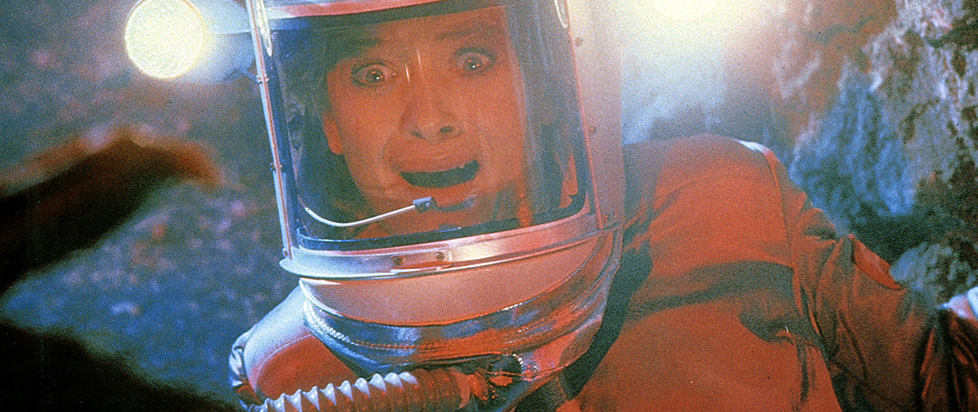

My next surprise was that Inseminoid is actually pretty tense an atmospheric, as extremely low-rent Alien knock-offs go. Given that they didn’t have a lot to work with besides colored lights, some rocks, and a few pieces of corrugated sheet metal, it’s pretty impressive.

Sure, there are a couple of largely immobile alien puppets, but they don’t get a ton of screen time. Most of the threat comes from the impregnated Sandy, played by Judy Geeson, who has most recently shown up in a couple of Rob Zombie flicks. Here, she gives a delightfully unhinged performance consisting of a lot of screaming, face-pulling, and crying. It’s almost enough to make you forgive that you could be getting a monster instead.

I’m not going to argue that Inseminoid is feminist or anything approaching it, but it does have a surprising amount of gender parity. Unfortunately, it doesn’t have H.R. Giger doing production designs, so the crew does the best they can with rocks and red light, plastic coolers and clunky television monitors.

Other directors attempting to rip off Alien with such meager resources might not even try, but Warren throws in everything from a mine car chase to giallo-inspired kills to a surreal impregnation scene that’s equal parts 2001 and Rosemary’s Baby, albeit with about 1/1000th the budget of either.

Something That Frightened Him to Death: Terror (1978)

Something That Frightened Him to Death: Terror (1978)

Someone (or something) is knocking off the cast and crew of a low-budget horror flick – not to mention people only tangentially related to said cast and crew – in this amiable British take on the supernatural giallo.

Norman J. Warren has apparently admitted that he had just seen Suspiria when he was making this movie, and it shows, even if Terror isn’t really much like Suspiria except in that it only makes a little sense, there’s witches involved and Warren is sure to break out the colored gel before all is said and done. (In one kill sequence, a piece of glass even forms a guillotine straight out of Argento’s playbook.)

Like most of the other films in this set, Terror is somehow a lot more effective than its meager budget and nonsensical screenplay should allow. It’s also surprisingly ambitious in its set pieces, even compared to some of the more expensive films that it’s aping – see one bit with a car levitating among the treetops, in particular. (Chewbacca himself, Peter Mayhew, also shows up as a mechanic in one of the picture’s more effective stalking scenes.)

Terror opens with a period sequence of a witch being burned at the stake that will feel familiar to anyone who has seen City of the Dead. Then the closing credits roll, and it turns out that we’ve just been seeing the end of a cheapie horror feature in the Corman/Price/Poe vein.

Except, of course, in this case the feature was based on the real family history of the film’s producer, whose bloodline was cursed to the last member by the dying witch. Also, it seems that everyone associated with his ancestral pile – where, of course, the picture was filmed – has met a tragic and violent end.

Naturally, from there, the bodies begin piling up, along with plenty of wind machines and stalk-and-stab sequences. Sometimes, the people die as a result of clearly supernatural tomfoolery – a man is attacked by a mass of celluloid, a stage light plunges onto a victim, a car attempts to run down a police officer under its own steam – while other times a gloved killer stabs people with knives or strangles them with piano wire. At least, gloved hands stab people with knives. Is there a killer attached to them? Who knows?

Does any of it make sense? Not a ton. The witch handily looks just like the one in the movie, and if she’s cursed the bloodline, then why do so many random people get killed? None of that really matters, though. We’re here for the weird lighting and the levitating cars, not the scintillating dialogue or the intricate plot.

It Came from the Sky: Prey (1977)

It Came from the Sky: Prey (1977)

I’m going to go ahead and say it right out of the gate: The constable who sees a dog-faced alien and immediately starts punching the shit out of it deserves a better fate than he gets.

In Prey, also known as Alien Prey, a “deadly alien shape-shifter infiltrates a country house occupied to two lesbians, and proceeds to study their behavior, for a sinister purpose,” according to the IMDb synopsis. That’s pretty much what happens, it’s true, but it doesn’t capture how deeply weird Prey is.

The lesbian couple are in an extremely dysfunctional relationship, and the alien, who dubs himself “Anders Anderson” and doesn’t know what water is, ultimately acts only marginally less human than the film’s human characters. Which may be the only reason why his awkwardly ingratiating himself into their otherwise isolated lives is at all credible.

Jessica is a “caged animal,” as the alien himself points out. She vacillates wildly between terrified and giggly, while her lover Jo is a man-hating lesbian caricature who is domineering and possessive and almost certainly killed a guy, a conclusion that Jessica seems to come to early on, then keeps forgetting about and re-remembering as the plot gradually unspools.

There are plenty of strange and stilted scenes as the alien eats rabbits and chickens and foxes while acting as a prop to the confusing melodrama of the women’s disintegrating relationship. Jo absolutely melts down when she finds the chickens dead; they dress the alien up in drag and have a party where they play hide and seek; the alien falls into the swan pond in a sequence that culminates in an endless slow-mo shot of them all splashing around while music drones.

It may be the weirdest and cheapest movie in the set, but, like all the others, that weirdness is filled with moments of surprising power and effectiveness, even if the alien just has a smushed nose, red eyes, and pointy teeth in his “true form.” Basically, if you ever watched Xtro and thought, “Wouldn’t it be great if this had more lesbians and an even smaller budget,” then Prey is the movie for you.

Let’s Try the Left Hand: Satan’s Slave (1976)

Let’s Try the Left Hand: Satan’s Slave (1976)

Thanks to my decision to watch these in reverse-chronological order, I inadvertently saved the most graphic movie for last. (I am as surprised as you that Inseminoid is not the most graphic, but here we are.) It’s also the film with the most star power, thanks to Michael Gough strapping on a hell of a mustache for a turn as a kindly uncle-cum-evil head of a Satanic coven.

That’s not really a spoiler, as the movie makes the Satanic shenanigans pretty clear from the jump, starting out with a black mass complete with a great Halloween goat head mask, which takes some of the wind out of the sails of the film’s later attempts at “is it all in her head” rug-pulling.

Satan’s Slave establishes a whole lot of the trademarks that I had, by now, come to expect from the filmography of Norman J. Warren. It’s a low-rent take on a subgenre that was in vogue at the time (in this case, the Satanism shocker) that’s more successful than should be possible given its extremely modest budget and also-ran premise.

It has lots of full-frontal nudity, a few extremely effective scenes, and it gets a lot of mileage out of an English manor house – the same one that had been used a few years earlier in Virgin Witch and would be used again, by Warren, a couple of years later in Terror.

Satan’s Slave is also probably the goriest film in this set. It’s got a graphic eyeball stabbing, a knife stuck through someone’s mouth, and an extremely bloody jump off a building in which the human body breaks apart like a pastry filled with blood and bone.

Plot-wise, there may not be much in Satan’s Slave that we haven’t already seen before, and it may spend more time spinning its wheels than some of the other films in this set, but, like pretty much every other Warren title I’ve watched here, it’s also surprisingly creepy and often much more effective than its meager budget should allow.

There aren’t any levitating cars in this one, though, so, I dunno, you take what you can get, I guess.