Gundam It – Mobile Suit Gundam Thunderbolt Vol. 5

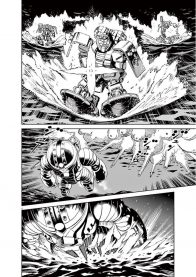

Gundam Thunderbolt’s fifth volume is split between two contradictory halves. The first, tracing a scuffle between Daryl’s reformed Living Dead Division and the fanatical legions of the Nanyang Alliance, brilliantly realizes every promise made in the best moments of the surprising prior installment. The turbulent waters – studded with submerged ruins left behind in the wake of the One Year War – and the overlush jungles of Southeast Asia as rendered by Ohtagaki aren’t merely beautiful to behold, lived-in and living environments full of menace and possessed of distinct personality. More importantly, they possess a sense of defined space that lends Ohtagaki’s lovingly detailed mobile suit skirmishes real boundaries and so real rules and so real consequences and so a real sense of danger.

Finally his obsession with speed and action can be put to proper use in a thrilling chase between Daryl and a trio of monks that takes full advantage of the hazardous environment to create a sense of stakes missing almost entirely from the showy but ultimately weightless battles of the Thunderbolt sector. Finally, those funkier elements of his storytelling style are allowed to outshine the self-serious shenanigans that studded so much of those  opening story beats. The sight of surfboarding GMs, or the vision of a bisected mobile suit leaking steam and blood and oil while speech bubbles full of scribbled prayers rise up around it like spirits ushering its soul on to wherever it is ruined mobile suits go, are too uninhibited and lacking in self-consciousness – too strange – to have appeared in the edgy proceedings of the opening story arc.

opening story beats. The sight of surfboarding GMs, or the vision of a bisected mobile suit leaking steam and blood and oil while speech bubbles full of scribbled prayers rise up around it like spirits ushering its soul on to wherever it is ruined mobile suits go, are too uninhibited and lacking in self-consciousness – too strange – to have appeared in the edgy proceedings of the opening story arc.

Sadly, the second half of this volume recall too vividly those ugly early chapters. It’s a bafflingly hobbled affair that devotes dozens upon dozens of pages to a pair of disabled Zeon remnants tasked with a suicide mission by their idiot COs all to set the stage for Io’s glorious-looking but emotionally draining return while reminding readers for the millionth time that war is cruel and unfair. Again Ohtagaki cannot help but strike that familiar note of dramatic irony he loves so much, taking pains to show by contrast with the hapless Julio and Gregory how Daryl and the members of the Living Dead Brigade are, despite their abilities and their celebrated reputation, still nothing more than disposable tools to the Zeonic brass; the only difference between them and their less fortunate peers is the amount of responsibility each are saddled with. The only difference is how quickly they’re being fed into the meat grinder. That Io, despite the glorious appearance of the Atlas and his triumphant reception, is a sleaze who is heroic only by fluke of fortune. That the ruined lives spreading out in his wake aren’t necessary sacrifices to some greater cause but fodder for his egotistical joyride.

The critique is honest, and right: war is too often an absurd monument constructed to the vainglory of the monstrous and the petty. But Ohtagaki has been insisting this for volume after volume without ever offering an interesting investigation into how these mentalities come about or why they remain even now; he has no insight into why the supposed “glory of war” is such a persistent and pernicious myth in human history and no clue why people are so willing to throw theirs and a million other lives away in its pursuit. There’s nothing in Ohtagaki’s writing like the bitter tragedy that lent Gundam 0080: War in the Pocket real pathos, nothing close to the sense of futility that makes Iron Blooded Orphans such a refreshing addition to the franchise or the keen insight into history’s cyclical nature that make Tomino’s best Gundams seem so essential even when they barely work as plots.

The critique is honest, and right: war is too often an absurd monument constructed to the vainglory of the monstrous and the petty. But Ohtagaki has been insisting this for volume after volume without ever offering an interesting investigation into how these mentalities come about or why they remain even now; he has no insight into why the supposed “glory of war” is such a persistent and pernicious myth in human history and no clue why people are so willing to throw theirs and a million other lives away in its pursuit. There’s nothing in Ohtagaki’s writing like the bitter tragedy that lent Gundam 0080: War in the Pocket real pathos, nothing close to the sense of futility that makes Iron Blooded Orphans such a refreshing addition to the franchise or the keen insight into history’s cyclical nature that make Tomino’s best Gundams seem so essential even when they barely work as plots.

He’s belaboring a point already made (and clumsily so) much in the same way he belabors Io’s return in this edition. The fourth volume concluded with an announcement that the cocky Federation ace would be onboard to support the crew of the Spartan, after all; why then waste the back half of the next volume bringing about that reunion rather than throwing him and the crew into a set of skirmishes the same way Ohtagaki immediately launched Daryl and his company into conflict? Despite the beauty of the art, the Atlas Gundam’s grand, explosive display hardly even looks that impressive when one considers how dull the narrative circumstances surrounding it are, how rote the danger is.

Which, again, is the point – the reality of those Zeonic pilots gives lie to the myth of Io’s heroism – but what is the point in making this same observation again and again and again? It’s difficult to imagine that Ohtagaki finds joy in it, especially considering how much more exciting the opening portion of this book is and how delightful the encounter with the space monks was in volume 4. One can only then think he’s so preoccupied with his own pretensions to “depth” that he’ll let them crowd out what is best (and not coincidentally what is dumbest) in his art. It’s a shame; one wishes somebody could tell him there’s no shame in creating dumb, strange fun, or that the supposed “glory” he thinks he’ll attain with a “serious” narrative is as illusory as that prestige his idiot characters scramble after.