Verse and Controller

The following is a reprint from Unwinnable Weekly Issue Thirty. If you enjoy what you read, please consider purchasing the issue or subscribing.

———

I was a poor reader of The Lord of the Rings. As a young teenager fascinated with all things fantasy, Tolkien was of course one of the first authors whose works I devoured. Indeed, I was so adept at devouring that I did very little savoring. Every time I encountered passages of the poetry scattered throughout Tolkien’s fiction my instinct (and practice) was too take a deep breath, scan quickly and move on. In my thinking, the poetry was little more than a distraction from the really important story – the adventures of Tolkien’s characters as they travelled through Middle-Earth. Why waste time reading some stilted poems?

Of course, poetry was in many ways at the very center of what Tolkien was trying to create, a fact that I appreciate more now that I study and teach literature for a living. Still, I bet my teenage self wasn’t alone in avoiding the poetry in Lord of the Rings. Yet Tolkien’s professional life was steeped in poetry, and one of his greatest admirers, W. H. Auden, was also one of the twentieth century’s greatest poets. Why is it then that the poetry of Middle-Earth can be so tempting to gloss over? Perhaps in some ways poetry is more likely to be disregarded when it’s presented within some other medium.

Videogames might seem like the least likely candidate for a medium in which poetry could thrive, and yet the worlds to which games give us access are often teeming with poems. But the poetry here is often marginalized in a way that resembles my own poor reading of Tolkien. My only published poem actually appeared in a videogame, and the experience helped me to recognize the disparity between the effort I put into crafting the text and the poem’s final placement in the game.

To be honest, I’m not exactly thrilled with the poem now. The year was 2003 and I was in the midst of a massive geek-out episode in anticipation of the impending release of Cyan Worlds’ new game Uru. Cyan was the studio responsible for the adventure games Myst and Riven, games which cultivated my love of writing, narrative and, of course, games themselves.

Uru’s publication was paired with a unique community development project that sought to expand the game’s roleplaying possibilities outside of the game itself. The larger narrative of the Myst universe involves an ancient civilization that dwelt in an enormous cavern somewhere underneath the New Mexico desert. Uru sought to add a layer of realism to the original Myst games by suggesting that this cavern had actually been discovered in the real world, and the players of the game were explorers who had been invited to the ancient subterranean city.

In anticipation of the game’s release, the community website ran a contest where players could submit poems based on the Myst mythology and the winning entries would be included in the game itself. I spent quite some time working on my entry; I even tried to learn some of the fictional D’ni language from the games in order to include some phrases in my text.

When my poem was chosen, it seemed as if my creative effort would become something significant to thousands of other players, but my exuberance was tempered when I finally got the chance to play the game. In the community neighborhoods there was a small lecture hall, out of the way, and in that lonely room my poem sat in a book upon the lectern. It’s there even now, in Uru’s current free-to-play iteration, Myst Online; I went back recently and was struck by the game’s emptiness and my poem’s position, hovering on the margins.

———

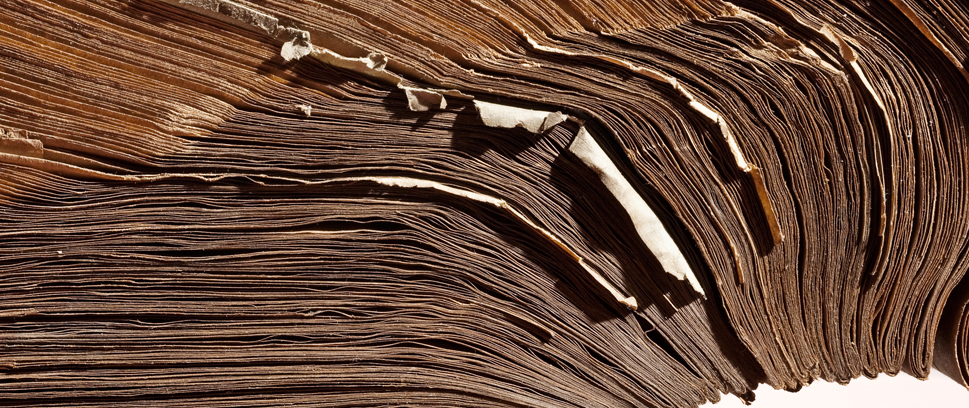

In many ways my experience mirrors the ways that we as players tend to relate to poetry when it appears in videogames. Rather than drawing our attention and interest, poetry is little more than a marginal bit of textual trimming that we hurry past on the way to completing the next quest, defeating the next enemy or traveling to the next checkpoint. What’s more, I’ve found that despite my own sense of marginalization, my behavior as a player remains unengaged with the poetic artifacts that are scattered across so many games. In the case of Ni No Kuni, there is a book called The Wizard’s Companion that players can access throughout most of the game – a book central to Oliver’s story, as it is how he begins to discover his power as a wizard. However while playing Ni No Kuni, my interaction with The Wizard’s Companion tended to be more perfunctory. The book became little more than part of the game’s design that I needed to navigate in order to progress in the narrative. Yet The Wizard’s Companion is a remarkably intricate videogame text that draws on poetic style and history in order to suggest that within Ni No Kuni’s “other world” poetry is deeply connected to the power of magic.

The “Wiseard’s Pledge,” with which the book opens, is written in a style that is meant to approximate the English of centuries past by using archaic spellings like “trauell” and “maysterie,” the same kind of archaic imitation that Samuel Taylor Coleridge used in “The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere” and Edmund Spenser used in “The Shepheardes Calender” Insertions of aged language are common in the commercial world, as “shoppe” and “olde” adorn many businesses, but in the case of The Wizard’s Companion, Ni No Kuni offers players an opportunity to become immersed in a textual appreciation of poetic language. In its original release on the Nintendo DS, players actually drew the spells using the DS’s touchpad, making The Wizard’s Companion as much a companion for the player as for Oliver. But when the game arrived on the PlayStation 3, this mechanic was replaced by a more traditional menu system that we often associate with JRPGs. In a sense, this alteration, made necessary by the differences between the two platforms, also made it less likely that players would spend time appreciating the companion.

It is in the conclusion to The Wizard’s Companion that its fealty to poetry becomes clear. This final poem invokes the deep history of poetry by connecting poem and prophecy. It’s a fitting end, because the poem actually gives away key elements of the game’s plot, but does so in a way that alludes to famous prophetic poems of the past. In describing the girl “emtombed there in her iv’ry tower,” Ni No Kuni invokes Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott,” a narrative poem set in the world of King Arthur, in which the titular Lady is trapped on a small island of “four gray walls, and four gray towers,” held there indefinitely by a prophetic curse. Yet unlike Tennyson’s tragic poem, The Wizard’s Companion’s final line draws upon a popular phrase from Hamlet: “This above all: to thine own self be true.” Whereas in Shakespeare’s play the line’s meaning is more troubled, for Oliver, this last line of his wizard’s tome becomes a call to action, and a final prophetic invocation of the victory waiting for the game’s characters at the close of their story.

If players never take the time to delve deeply into The Wizard’s Companion, then these details are lost. The poeticism of this central text to the game’s narrative may remain unearthed throughout the entire game. And, some might argue, in a game whose world is already richly imagined through Ni No Kuni’s visual design, perhaps the poetry of The Wizard’s Companion is unnecessary. Indeed, perhaps poetry is a poor fit for videogames anyway. After all, although I spend a lot of time reading poetry, I tend to conceive of my time with poetry as distinct and separate from the time I spend playing games. (However a recent article comparing the current state of videogames with 20th century confessional poetry raises an intriguing point about the ways in which videogames have some formal parallels with the medium.)

———

My favorite poems are long narratives; Beowulf, Milton’s Paradise Lost and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh require readers to sit with the text for long periods of time. These poems point to a time when stories would have been told as poetic performances. With games like Skyrim or Mass Effect, there is a sense of kinship in the ways these games craft a lengthy and fantastic narrative experience. Indeed, both games harken back to poetic origins by incorporating oral poetry into their stories. Unfortunately, both presentations fall short of their poetic heritage.

In the case of Mass Effect, the Krogran Charr is shown to be a love-stricken poet whose public performances are presented in a way reminiscent of the Vogons from Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, whose poems are so bad they can drive people mad. While Charr’s romantic efforts can be successful in the game, they conclude with his beloved’s insistence that he stop reciting poetry.

On the other hand, Skyrim – a game whose heritage is clearly linked to Beowulf – creates a conflict for players with its representation of the Bard’s College. While it’s possible to join the college, which is tasked with training and sending out bards to sing and perform narrative poetry, players are not able to meaningfully participate in this pursuit. Granted, finding a way for players to perform a bard’s task presents a particular kind of challenge, after all – Bethesda probably didn’t want Skyrim to include a karaoke mini-game – but the very fact that a game that draws so specifically from Old English narrative poetry is unable to immerse players in that tradition shows the particular challenges that poetry presents for videogames.

———

Long narrative poems are only one small slice of the wealth of poetic forms that writers have created over the centuries. Perhaps shorter forms like the sonnet better approximate a way for games to draw upon and incorporate poetry into the experience of the game itself. In the 16th century, Sir Philip Sidney penned his famous “Defense of Poesy,” arguing (among other things) that the poet was meant to either improve upon nature or invent new forms not yet present in nature; while Sidney obviously did not conceive of anything like videogames in his description, the idea of invention and creation that he bestows on poets is indicative of the possibilities that they provide as interactive experiences. Games have begun to show us what an interactive poem might look like, and they so far have tended toward the kind of brevity found in sonnets.

Over the last few years, I have had the opportunity to score the AP Literature exam and many students demonstrate in their essays an understanding of the basic outline of the sonnet – an idea that is introduced, elaborated upon, complicated and finally resolved (sometimes with a twist). Understanding a sonnet often requires that we re-read and contemplate before fully forming our conclusions. Recent games like Gone Home and Brothers have created what might be called interactive sonnets, because of the way that they capitalize on their relative brevity in order to focus the player’s attention on a singular idea.

In the case of Gone Home, exploration exists as both a textual and a spatial manifestation of the game’s interaction. While we are seeking to open up the corridor’s of this mysterious house, we are also urged to uncover the hidden passages of the absent family members who inhabit it. Passage in Gone Home becomes a reference to both text and space, as the slips of paper scattered throughout the house become both the foundation for the narrative as well as the clues that allow us to explore new architectural passages. The reason that Gone Home then becomes an interactive poem is the way that this process enacts the very searching and discovery that Sam is going through as she learns who she is and who she wants to become.

Rather than simply dropped a narrative onto the design, Gone Home asks us to participate in the narrative by (re)creating the growing personal awareness that Sam records in her scattered diaries, letters and stories.

Similarly, Brothers manages to evoke a wealth of emotions in its conclusion simply by having the player press a button and use an additional joystick. In some ways, Brothers’ use of a distinctive control scheme is particularly indicative of the sonnet in the ways that it begins with a concept and then proceeds to elaborate upon and complicate that initial idea. Where it truly excels in its creation of a poetic experience is in the last moments when the younger brother has lost his elder brother and must complete their journey alone.

In that fraction of a second, when we realize that we must return to the original control scheme that was introduced in the game’s beginning, invoking the presence of the lost brother so that his younger sibling can finish alone what they began together, the game accomplishes something that is quite rare in videogames – the seamless fusion of mechanic, narrative and interaction. Brothers suggests the ways in which videogames can themselves create new forms of poetry in which people can enact the very ideas that the narrative conveys.

Poetry often has a way of sneaking up on us; it’s an art that lies in wait, often surprising us when we least expect it and allowing us to realize that it’s been there all along. Poems bring a sense of depth and gravity to language and experience; and it is in the experience that videogames can practice the kind of invention that Philip Sidney alluded to almost 500 years ago. Poetry gives us access to the deepest qualities of human thought and feeling; as Robert Browning wrote in the conclusion to The Ring and the Book:

Art remains the one way possible

Of speaking truth . . .

. . . So may you paint your picture, twice show truth,

Beyond mere imagery on the wall, –

So, note by note, bring music from your mind,

Deeper than ever e’en Beethoven dived, –

So write a book shall mean beyond the facts,

Suffice the eye and save the soul beside.

Browning gives here three examples under the aegis of Art: painting, music and writing. All three are encompassed in videogames – visual, aural and textual – and as games continue to change and grow, more opportunities will develop for finding ways to generate poetry through games. So, perhaps we should look to discover both more poetry in our games and also more games that are poetry.