I Know I’m Human

Paranoia is the dark heart of John Carpenter’s The Thing. A dozen men struggle to survive while trapped in an Antarctic research base with a shapeshifting alien capable of flawlessly duplicating and imitating any creature it consumes. Who is still a man? Who has been turned? Have I been turned without realizing it? Am I still me?

This is not a new idea. Carpenter’s film, of course, is a remake of the 1951 Howard Hawks film The Thing from Another World, which in turn was adapted from the 1938 novella Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell. Both wrestle with contemporary anxieties, Hawks with the Red Scare and Campbell with pre-war fears like socialism and the German American Bund. There’s a long heritage of tales, like Invasion of the Body Snatchers, warning about the enemy within in the intervening years.

The destruction and replacement of identity by something else is the most potent theme in horror, but remains largely confined to the realm of internal monologues and omniscient narrators in written fiction. Tackling it in film leads to largely unsatisfying results. But not The Thing; The Thing is exquisite.

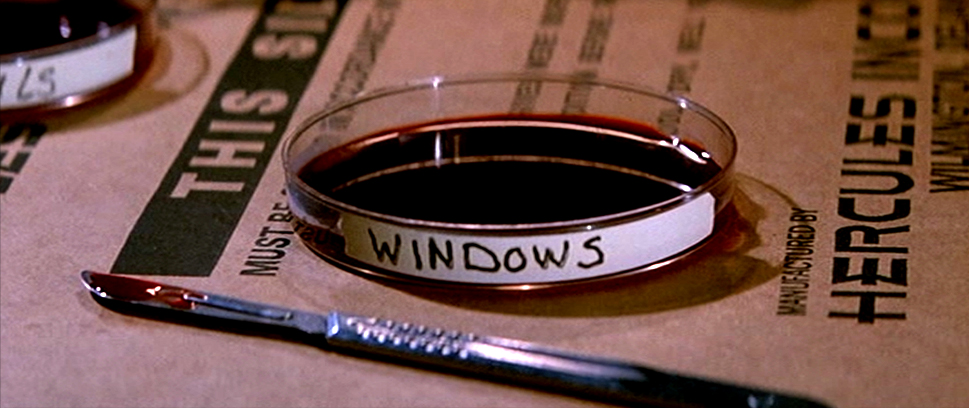

Just take the infamous blood test scene – three men tied up on a couch, two others watching them with flamethrowers at the ready, two dead bodies in the background. The theory is that pieces of the Thing act independently and will try to survive if threatened – if a blood sample leaps away from a heated wire, say, then that man must be a Thing. As MacReady gets ready to put the theory to the test, no one, including him, is sure what will happen. The tension is unbearable.

Even after watching it countless times over the years, I’ve never been certain who was a Thing and when they turned. It’s a slippery film. The way you see things now may change entirely the next time you see it. As the viewer, you’re forced to become just as suspicious as the men of US Outpost #31.

Right now, though, I think I’ve got it solved for good.

There are two great mysteries in The Thing. The first: who is the first man to be infected? We see his shadow on the wall just moments before the dog-Thing attacks him, but we never see his face. The second mystery: is either MacReady or Childs, who both survive until the bleak end of the movie, actually a Thing? If we can solve the first, we just might be able to figure out the second.

Through careful viewing, we can eliminate everyone from the suspect list except Norris, the geologist, and Palmer, the assistant mechanic. It is a 50/50 shot for either man to be first victim. Thankfully, the producer, Stuart Cohen, has copped that they intended the shadow to be Palmer (though they used a stuntman in the scene to preserve the mystery entirely).

The next piece of the puzzle is Fuchs, who delivers the information that even the smallest particle of a Thing, like saliva, could infect a person. He then suggests that the men stick to canned food. This is important because, until this point, we’ve only seen the Thing duplicate by violently subsuming a person, devouring them, then using the extra mass to create another Thing via a kind of asexual reproduction.

Every transformation in the film is violent, with the lone exception of Norris. There is no indication that he was a thing until after he dies of an apparent heart attack. I’ve always read this as a ruse on the part of the Norris-Thing, but that doesn’t make sense – that just puts it in a more vulnerable position. But what if a tiny Thing-particle infected Norris and slowly converted him, cell by cell? What if it we didn’t witness his heart attack, but rather the final moment of his transformation?

And what would that mean for Childs, who shared a joint with the Palmer-Thing much earlier in the film?

It might mean that Childs could pass the blood test, for one. The Thing-cells could have started converting his lips and mouth and digestive tract first and not done anything to his blood at the time of the test. Even at the end of the movie, Childs might not realize he’s a Thing.

(The oft-cited gotcha moment at the end of the film – that Childs’ breath doesn’t cloud up in the cold air like MacReady’s – is a trick of the lighting, not the revelation that Things don’t breathe. The Bennings-Thing breathes just fine when the men run him down and torch him outside the compound.)

And there you have it – the two main mysteries of The Thing solved. At least until I watch it again.

That’s the beauty of the movie, the reason I keep coming back. Sure, the setting is great, the performances spot-on and the special effects unbelievable. Yes, I am a sucker for Lovecraftian creatures, and the Thing is one of the best ever put to film. But those things pale in comparison to the movie’s ability to remain open to interpretation in an unpretentious way.

Carpenter’s The Thing came about in a strange time. In 1982, people flocked to see the optimistic E.T. the Extra Terrestrial and ignored this most cynical take on aliens. People weren’t scared of the Cold War any more, at least not in the same way that fueled the science fiction of the 50s, and they hadn’t yet learned to fear HIV/AIDS. With no undercurrent of negative emotion to tap into, The Thing winds up a kind of post-modern horror film, ruminating on the anxiety of anxiety.

That’s why when AIDS did enter the vernacular, all the blood and paranoia of The Thing seemed prescient. Or, after 9/11, when it seemed to be about the terrorists hiding in our midst, or today, the way it taps our fear of epidemics like ebola. Even as it is about all those things, and more, it can also be about none of those things. It can just be a simple horror story about a dozen isolated men trying to survive something they barely comprehend.

It all goes back to the blood test scene. Three men tied to the couch, two others watching them, flamethrowers at the ready, two dead bodies in the background. No one knows what is about to happen. MacReady performs the test, tapping each dish of blood with the hot needle, drumming like a march to the gallows. Human. Human. Human. Then BANG, the needle touches Palmer’s blood and it leaps, screaming, out of the dish. Palmer starts to change and the men he’s tied to on the couch start to freak out, screaming. Just like you, out there in the audience.

The Thing, like its titular creature, adapts to the viewer. It changes shape to suit what we dread to find. Amorphous. Terrible. Formless. Everything and nothing, all at once.

———

Dead serious: I cut 250 words out of this piece that detailed my reasoning for eliminating everyone but Norris and Palmer as the shadow. Available upon request.

This is part of an ongoing series of essays looking at the horror films of John Carpenter. Previously, I looked broadly at Carpenter’s life and career, the classic Halloween and The Fog. Next up is Christine. Feel free to disagree with me on Twitter, @StuHorvath.