No Clues

In less than a week, I’m going to visit my parents. This alone is a bit of an event; we usually see each other every six or eight months, but it’s been three years since I saw them in the house that I lived in for the first 18 years of my life. Not all that much has changed there – my childhood bedroom has morphed into my mother’s second closet, but the stacks of Garbage Pail Kids and mid-’80s Mad Magazines are still in their rightful places. Like always, I’ll run errands with my mom. I’ll dig old bikes out of the garage, go to same pizza place where I nursed an 8-year-old’s crush on the waitress, drive aimlessly around the college town where I grew up. And like always, I’ll sit with my dad and crack jokes.

But this year, for the first time, I’ll have to tell him who I am.

———

[pullquote]Everyone knows the Sunday puzzle, but Friday and Saturday are the real test.[/pullquote]

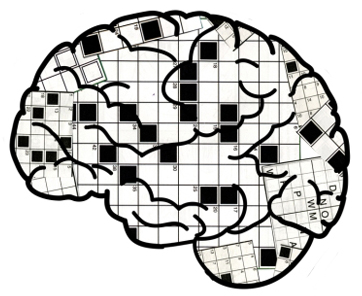

Every night I could remember before I went away to college, my father would lie on his back on his bed and do the New York Times crossword puzzle. He had a vinyl-backed clipboard and a Bic felt-tip marker that could write upside down, and he’d plow his way through, one square at a time. Downstairs, my mother would work a separate copy at the kitchen counter, though more patiently and in pencil. (She was a librarian, and the library’s NYT subscription subsidized the Rubin family’s habit for decades.)

“Everyone knows the Sunday puzzle,” he liked to say once I got old enough to crawl under his arm and try to help, “but Friday and Saturday are the real test.” As the weekend crept into view and the puzzles got tougher, he’d chew them more slowly; a Sunday puzzle could sit in the clipboard for days while he gnawed away. More than anything – more than brute-forcing a Saturday puzzle, more than cracking the theme of the super-sized Sunday grid – my father loved seeing Mel Taub’s name appear two Sundays a month under the main attraction.

Taub’s specialty was the puns-and-anagrams puzzle, a lightweight version of British-style cryptic crosswords that hinged on wit more than obscure vocab items. (This was before Will Shortz came around and the world of crosswords became fun; back then, the NYT crossword was the province of Eugene Maleska, a name I always imagined as being attached to Abe Vigoda, after Abe Vigoda ate a lemon and was given a wedgie at the same time.) Puns-and-anagrams puzzles, when they came around, were a concentrated dose of silliness that he thrived on. “1,000 cheers for spies” became MOLES (M + olés); “In which a hat is called a lid, etc.” became DIALECT (anagram of “a lid etc”). My dad was a fan of Gilbert and Sullivan librettos and terrible jokes, so he was powerless against the wordplay. I was a fan of rap – which didn’t need an “old-school” before its name, since it was the only kind that existed – and terrible jokes, so I was too.

It was rare for something fun to unite us. It was rare for anything to unite us, really. Money burned a hole in my pocket, as he liked to say, and my love for videogames just meant that the hole was more recognizably token-shaped. The easy fix was a ban on the arcades in town: Space Port, Aladdin’s Castle, even the Rack & Cue. My consolation prize was an Atari 2600 that my cousins had outgrown, hooked up to a tiny black-and-white TV in the basement; if I couldn’t gorge on  Spy Hunter and Gauntlet, at least I had Pitfall and Spider-Man. As I grew into my teens and videogames gave way to other distractions, we found other things to butt heads over, but Mel Taub was always our DMZ. When your brain shifts gears, it doesn’t leave room for the rest of your thoughts to come along – so we rearranged strings of letters, unlocking new meanings, while our differences sat by the door.

Spy Hunter and Gauntlet, at least I had Pitfall and Spider-Man. As I grew into my teens and videogames gave way to other distractions, we found other things to butt heads over, but Mel Taub was always our DMZ. When your brain shifts gears, it doesn’t leave room for the rest of your thoughts to come along – so we rearranged strings of letters, unlocking new meanings, while our differences sat by the door.

———

“I didn’t want you to worry,” my mother said on the phone. It was 2002, and I was sitting in my apartment in the East Village, holding the phone to my ear and staring out into the air shaft. A few weeks before, my father had apparently suffered something the doctor called a “transient ischemic attack,” which is what you call a stroke when you don’t want to call it a stroke. There were no lasting effects, she maintained, and my dad was doing just fine – he’d gone on a blood thinner in addition to the statins he was taking for cholesterol management, and there was no reason to think it would happen again.

Then, a year or two later, he blacked out while driving home from class, only coming to when the car tires bumped against the curb. No one was on the road, thankfully, but it made him paranoid; soon, the man who routinely drove 12-hour stints on family vacations didn’t like driving on highways. He began to retreat inward, one tiny step at a time. He got quieter, smaller.

When I’d finally gone off to college and our relationship began that long transition from discipline to friendship, he had mellowed considerably, but this was different. Soon, my mother told me that he’d begun to have trouble finding a word, or remembering an acquaintance’s name. I don’t remember when the word “dementia” first entered the picture, but it hung around for years, too many of them, refusing to yield to his sudden inability to do a crossword puzzle or tell time.

By now, the Alzheimer’s has made him soft and sweet in a way I never imagined anything could. Once, there was a man with a Rasputin-thick beard who yelled at the drop of a hat and couldn’t get anywhere fast enough. Now, the world moves around him and blank contentment is his only expression. He tells waitresses how wonderful they are. His lips tremble, just a little, all the time. He smiles and waves when he sees his reflection in a mirror. He introduces himself to his daughter. He’s seventy fucking three years old.

[pullquote]Every time I hear someone speaking about the importance of living in the moment, I think of my dad in a chair, looking at nothing, thinking of nothing, and I want to throttle them.[/pullquote]

Physically, he’s fine; he has 15 or 20 years in front of him. Not good years, just…years. Years of single moments, each lived with no connection to any that came before or any that lie ahead. And that’s terrifying. Every time I hear someone speaking about the importance of living in the moment, of mindfulness, I think of my dad in a chair, looking at nothing, thinking of nothing, and I want to throttle them.

I recently found an archive of Mel Taub’s old puzzles online; I fired one up and worked through it for the first time in years. I may bring one of them with me, to sit with my dad and fill one out. I don’t expect it to mean anything to him – this is for me. The years we’ve had together are the years I’ll remember, even if he won’t, and I just want those years to have one more experience without an asterisk, one more conversation before he’s all the way gone. His brain has already shifted gears for good – I understand that – but it’s still no reason that we can’t sit together in our DMZ one last time, with a pen and a pun, while the rest of our lives rage on outside.