The Real Thing

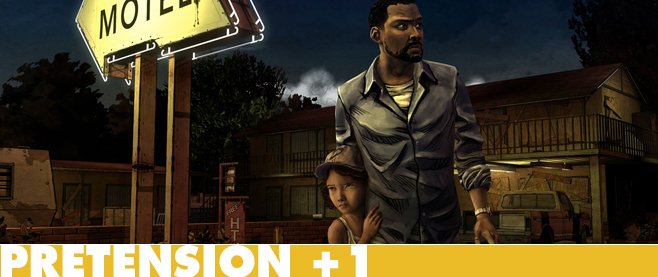

The phrase “just like family” exists because of an understanding that blood and sacrament aren’t the only adhesives that make people stick together. In the excellent videogame adaption of The Walking Dead, this truth is explored by putting familial connections through their paces. It, like all zombie stories, is the tale of people struggling to survive. The game’s protagonist, Lee, becomes the adoptive father figure of a small girl named Clementine. At first Lee’s protection comes as a kind of moral obligation. Clementine is on her own, her parents likely dead – no good person would leave a child to die at the hands of zombies – but, as the pair suffer through brushes with death (and worse), their connection becomes something else.

Eventually Clementine and Lee find other survivors. Many are pairs of people thrust into relationships by the end of the world. And others are families clinging together against the tide of death. Central to much of the game’s drama are Kenny, Katya and Duck – a father, mother and son who travel alongside our hero and his ward. The Walking Dead’s grim emotional arc holds these two units up for comparison – the improvised bond between Lee and Clementine and the blood connections between Kenny and his kin.

Eventually Clementine and Lee find other survivors. Many are pairs of people thrust into relationships by the end of the world. And others are families clinging together against the tide of death. Central to much of the game’s drama are Kenny, Katya and Duck – a father, mother and son who travel alongside our hero and his ward. The Walking Dead’s grim emotional arc holds these two units up for comparison – the improvised bond between Lee and Clementine and the blood connections between Kenny and his kin.

The Walking Dead is cruel. And in some of its incarnations, it feels somewhat psychopathic – especially in the way that it deems to learn more about relationships by destroying them. With a grim, unfeeling detachment, Robert Kirkman’s comic book smashed familial units against the wall, then sifted emotionless through the pieces. I felt no such disconnect during the ugly moments in Telltale’s game. Every wrenching decision and terrible loss was like a kick in the guts and though the process was fraught with blood and tears, I admired the game’s conclusion. It’s not a spoiler to say that in the end The Walking Dead discovered that the bond formed between Lee and Clementine, two strangers, is made of the same vital material as a family formed via biology and religious rite.

It’s a long way to go to validate the non-traditional family.

Not long ago my wife and I flew to Denver to watch an old friend, David, marry the love of his life. The ceremony and reception were to be held in a small country club on the outskirts of the city. My wife, Alexis, was a little surprised when we arrived. David’s family, she said, treated me like a celebrity. I was greeted with beaming smiles and warm hugs from people I hadn’t seen in ten years. That’s because, during rough times, the Berman clan treated me like a son. I ate at their table and slept under their roof. They provided stability for me when there was none to be found at home. When tragedy struck the people who had been so kind to me, I learned that the emotions that grow out of improvised families have a potency and complexity that can’t be denied.

Not long ago my wife and I flew to Denver to watch an old friend, David, marry the love of his life. The ceremony and reception were to be held in a small country club on the outskirts of the city. My wife, Alexis, was a little surprised when we arrived. David’s family, she said, treated me like a celebrity. I was greeted with beaming smiles and warm hugs from people I hadn’t seen in ten years. That’s because, during rough times, the Berman clan treated me like a son. I ate at their table and slept under their roof. They provided stability for me when there was none to be found at home. When tragedy struck the people who had been so kind to me, I learned that the emotions that grow out of improvised families have a potency and complexity that can’t be denied.

I spent the ensuing years fashioning jury-rigged families out of friendships. My college roomates became stand-ins for brothers when distance put my sister and mother out of arm’s reach. Co-workers and colleagues have circled around me to huddle against the cold. Finally, I met in Alexis, a woman who would agree to forming a familial unit according to the manual. Everybody tells me that it will be different when I have a son of my own – that my life will change forever. I have no doubt that this is true, but I refuse to believe that it will be all that different. I’ve seen the glue that holds people together. And I know that it doesn’t discriminate.

———

Pretension +1 is a weekly column about the intersections of life, culture and videogames. Follow Gus Mastrapa on Twitter @Triphibian.