Childhood on a Disc

Once in a blue moon, someone will ask me what my favorite videogame is, and I can only wonder what they think I’ll say. If they know me as a beyond-hopeless gamer with an encyclopedic knowledge of everything that came out, they probably expect a game nobody else has ever heard of. Or maybe that I’m a purist who believes nothing can top widely-known classics like Pitfall! or Tetris or something. Well, I’m sorry that I’m about to shatter the mystery for you, but it’s the former: my favorite game is Boku no Natsuyasumi, or “My Summer Vacation,” a PlayStation game that came out only in Japan.

I grew up in the Pacific Northwest, so it was inevitable that I’d foster a love of natural scenery. Not just forests and mountains, but even the plots of land that people claim around them and live on. I’ve loved videogames just about as long, but games didn’t always give me a lot of scenery to appreciate. That changed in 2000, when I read in an anime magazine about a new PS1 title from Sony that was essentially the scenery-filled game I didn’t know I needed. Fortunately, it had more than enough substance, too.

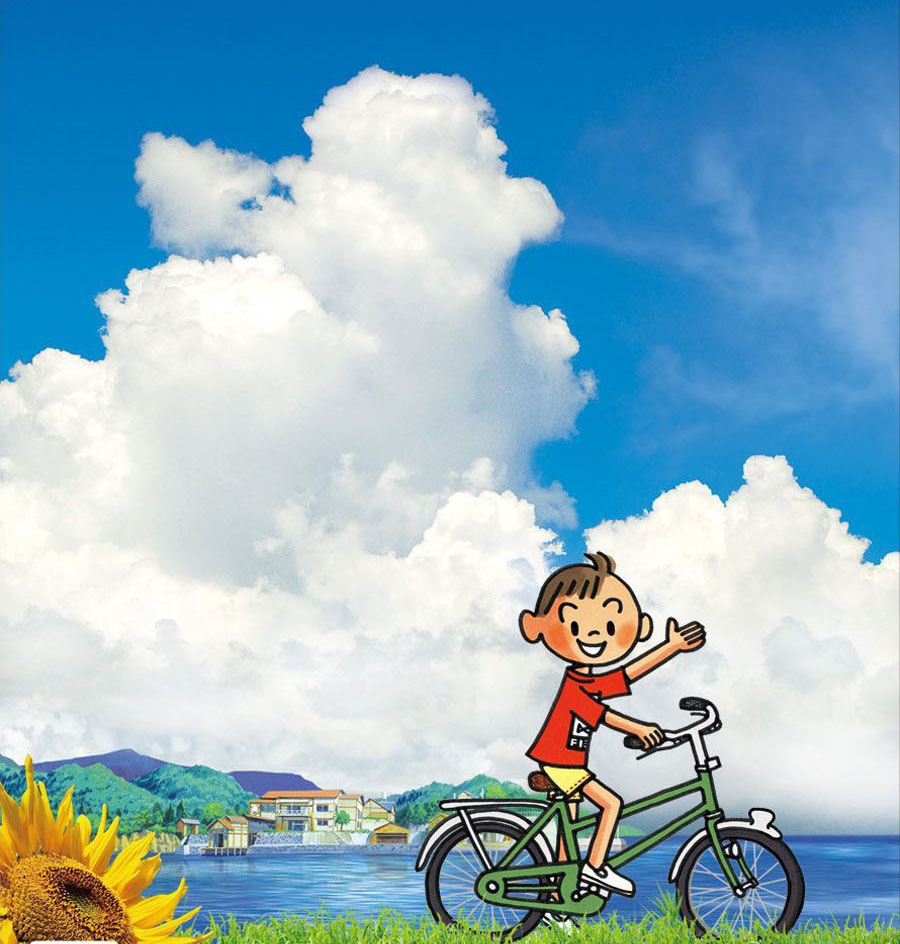

Boku no Natsuyasumi (“Bokunatsu” or “Boku” for short) is a self-described “nostalgic adventure” set in 1975, and focuses on Boku, a 9-year-old boy from the city who is sent to his aunt and uncle’s house in the country for the month of August – partly so he can experience something new, and partly because his mom is about to give birth to a new sibling. “Boku” is a punny name, because it’s a boyish word for “I” or “me” in Japanese. It’s also a device to get you to pretend you’re him – the game is the recollection of the adult Boku, who narrates the story on occasion. For 31 in-game days, you’re more or less free to run Boku around the property as much as you want (until dinnertime), though parts of the area only open up after being around for certain story events. The idea is to build up a pile of summer memories, which Boku records in his picture diary, and ultimately go back home with an experience that shapes his life for the better. And Boku is a precocious little kid, so while it takes a few days for him to warm up to the outdoors, pretty soon he’s asking cute naive questions and playing beetle sumo wrestling with the local kids in no time (yes, that’s an actual mini-game).

Boku no Natsuyasumi (“Bokunatsu” or “Boku” for short) is a self-described “nostalgic adventure” set in 1975, and focuses on Boku, a 9-year-old boy from the city who is sent to his aunt and uncle’s house in the country for the month of August – partly so he can experience something new, and partly because his mom is about to give birth to a new sibling. “Boku” is a punny name, because it’s a boyish word for “I” or “me” in Japanese. It’s also a device to get you to pretend you’re him – the game is the recollection of the adult Boku, who narrates the story on occasion. For 31 in-game days, you’re more or less free to run Boku around the property as much as you want (until dinnertime), though parts of the area only open up after being around for certain story events. The idea is to build up a pile of summer memories, which Boku records in his picture diary, and ultimately go back home with an experience that shapes his life for the better. And Boku is a precocious little kid, so while it takes a few days for him to warm up to the outdoors, pretty soon he’s asking cute naive questions and playing beetle sumo wrestling with the local kids in no time (yes, that’s an actual mini-game).

No matter where you’re from, summer vacation has its little clichés. In Japan, movies and other media about childhood summers seem to always feature incessant cicada chirps, bug catching, fireflies, local summer festivals and a hell of a lot of sunflowers. Boku no Natsuyasumi is not above any of that, and Boku’s vacation is only a month (like with many Japanese schoolchildren), so those tropes form the wrapper around his larger story.

And of course, there’s that scenery. The game is filled with painted backgrounds of the Japanese countryside that the Playmobil-esque characters inhabit. As Boku explores the forests, streams, fields and hills, the screens and “camera” change to give every piece of the game the look of a  landscape portrait. Given that, the gameplay is basically the same as early Resident Evil games, but in something with a polar opposite tone.

landscape portrait. Given that, the gameplay is basically the same as early Resident Evil games, but in something with a polar opposite tone.

Boku no Natsuyasumi is actually a fairly long-running series – it’s had three sequels over ten years, and everything I’ve described so far applies to all four of them, because they’re all about a 9-year-old Boku’s August away from his parents. Think of it as four parallel universes: Boku may look the same, but the family and setting changes each time, so he can’t really “be” the same. That may not make it any easier to imagine yourself as Boku, but it nonetheless gives you multiple opportunities to appreciate a semi-realistic world in a time before iPads.

Boku no Natsuyasumi 2 went a little bigger than the first game: it was on PS2, took place in a seaside town in Japan’s Izu peninsula and featured almost two dozen characters for Boku to meet, mostly because the aunt and uncle run a seaside inn. In between making friends with the grown-up patrons, his rambunctious cousins and village doctor, Boku also finds himself bringing together the teenage neighbor girl and the local boy she has feelings for. Boku 1 is my favorite for sentimental reasons, but Boku 2 is the all-around best in the series. In 2010, it was reintroduced on PSP like the first game (more on that in a minute) and got a host of additions and improvements that were enough to (in my opinion) take the game from great to near-perfect.

Boku no Natsuyasumi 3 sounds like it would have been the best one, though: it’s set in the Hokkaido farmland, where the series’ creator Kaz Ayabe grew up, and it was on PS3, so it was the first (only) opportunity to play a Boku game in HD. I was certainly ready to call it the best, because Hokkaido is probably the closest analogue to where I grew up. But the game feels a tad too different: the farm and the surrounding area feel narrow and cramped – and a wide shot of a big mountain in the distance is almost a taunt. You still have moments of exciting discovery, but they happen less often than in the other games, nor are there as many moments of heartfelt drama. And since it came out within the PS3’s first year, Boku 3 didn’t sell that well. On the other hand, because PS3 games are region-free, a lot of people outside Japan bought it and were introduced to the series, so it’s not all bad.

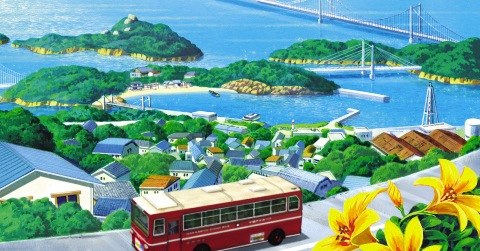

Boku no Natsuyasumi 4 thrust the calendar forward to 1985, and the Boku in this one goes to see his family in Setouichi, a harbor town that frames the seven Seto islands about 80 miles west of Kobe. It’s definitely the most varied terrain in a Boku game, and the story is back to a nicely flowing tale of devil-may-care fun among kids and adolescent love; you know, back when you thought holding hands in silence was just as good as a kiss. A new gameplay addition was a sort of energy meter that slowly depleted as days went on. You could easily refill it by eating the various foods in and around the house, but it’s not so easy to find or earn the money to buy them and the mandatory in-game dinners won’t help. I’d rank the game just after Boku 2, though maybe it would surpass it if it weren’t for that darn energy meter.

Boku no Natsuyasumi 4 thrust the calendar forward to 1985, and the Boku in this one goes to see his family in Setouichi, a harbor town that frames the seven Seto islands about 80 miles west of Kobe. It’s definitely the most varied terrain in a Boku game, and the story is back to a nicely flowing tale of devil-may-care fun among kids and adolescent love; you know, back when you thought holding hands in silence was just as good as a kiss. A new gameplay addition was a sort of energy meter that slowly depleted as days went on. You could easily refill it by eating the various foods in and around the house, but it’s not so easy to find or earn the money to buy them and the mandatory in-game dinners won’t help. I’d rank the game just after Boku 2, though maybe it would surpass it if it weren’t for that darn energy meter.

No Boku games have showed up after its 10th anniversary, but that’s understandable, considering the man behind them is working on something new for the future, in the Guild 02 omnibus game for Nintendo 3DS. In The Monsters that Appear on Friday, Ayabe tells another story based in 1970s childhood, only in a world where Godzilla-sized creatures roam Japan every Friday afternoon, just as they did on TV in our world. So far, that’s all that’s known about it, though its single screenshot suggests something slow and exploratory like the Boku games and not, say, a retake of Robot Alchemic Drive. But that’d be cool, too.

If you’re wondering how to play, or if you can play one of the Boku games, it’s an even split of pros and cons. As I alluded to earlier, PS3 and PSP games are region-free, so it’s easy to jump in with any installment. Obviously, not knowing Japanese won’t help you appreciate the nuances of the stories, but because the in-game clock moves forward with every screen change and some key story events are unavoidable, you can still complete them without much worry. I’ll be the first to admit I’m still a Japanese-language dunce, but I’ve still managed to love the Boku games not just for their pretty, evocative pictures, but for how they simply tell a kind of story that virtually no other commercial games have bothered to explore. Either way, you’re in for a beautiful, emotional, innocent adventure in childhood – and that’s pretty easily understood, don’t you think?

———

Ray Barnholt (@rdb_aaa) is a freelance games writer and the editor of SCROLL magazine. His favorite season is actually spring.