Greatest Unknown Anime – Part One: Elfen Lied

Having ingratiated myself with the masthead here at Unwinnable, I’ve taken it upon my shoulders to bring to you, my soon-to-be adoring public, a regular installment of reviews and criticism regarding one of the most under appreciated aspects of geek culture: Japanese Animation or, as the kids call it, anime. These will appear weekly and in no particular order.

Having ingratiated myself with the masthead here at Unwinnable, I’ve taken it upon my shoulders to bring to you, my soon-to-be adoring public, a regular installment of reviews and criticism regarding one of the most under appreciated aspects of geek culture: Japanese Animation or, as the kids call it, anime. These will appear weekly and in no particular order.

We begin with the first of my picks for the top five greatest animated series to come out of Japan with little or no attention stateside, despite readily available translations. Hajime!

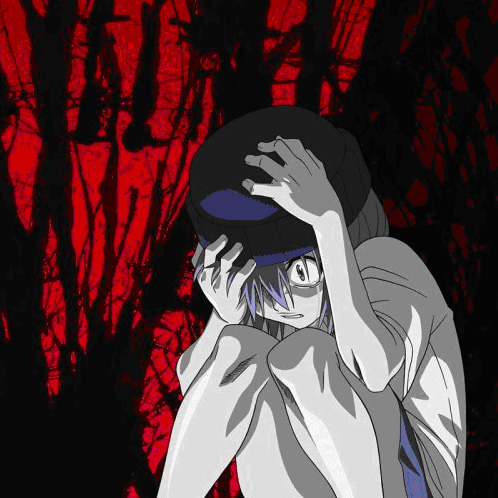

Elfen Lied (2004, 13 Episodes)

“Want some violence? I thought so.”

– James Galvin, ‘A Cast of Thousands’

If you can get through the first installment of director Kanbe Mamoru’s adaptation of the manga by Okamoto Lynn without your eyes widening at the sheer volume of blood, or perhaps the tremendous radii across which it spills, then you’re probably a burgeoning (or fully-realized) psychopath. But don’t worry. If, like the rest of us, you experience a kind of delightful queasiness, you won’t have to bear it for long—the violence segues nicely into several scenes of gratuitous female nudity.

I suppose this might not seem like an endorsement, but you’ve read the title of the article series, so there must be something more to Elfen Lied (pronounced ‘leed’ – the German word for ‘song’ ) than blood and breasts. And there is. The story follows a young man named Kohta who arrives at college in a village he’d visited as a boy. Here he lives with his cousin Yuka (who is madly in love with him, which is cool in Japan) in relative tranquility until a girl with horn-like protrusions and a bloody head wound washes up on the shore by their home.

I suppose this might not seem like an endorsement, but you’ve read the title of the article series, so there must be something more to Elfen Lied (pronounced ‘leed’ – the German word for ‘song’ ) than blood and breasts. And there is. The story follows a young man named Kohta who arrives at college in a village he’d visited as a boy. Here he lives with his cousin Yuka (who is madly in love with him, which is cool in Japan) in relative tranquility until a girl with horn-like protrusions and a bloody head wound washes up on the shore by their home.

This would be Lucy, a bloodthirsty, escapee mutant with a debilitating split personality. When she’s not in kill mode, she’s a language-less, pants-wetting, woman-child, a case study in massive compensatory regression and also maybe a condemnation of post-feminist politics, but I haven’t quite ironed that part out yet. Psycho-political analysis aside, Lucy’s presence in the lives of Kohta and Yuka raises incredible questions about Kohta’s past and about the deaths of his father and sister, questions which dominate the bloody, parallel threads of story throughout the show’s run.

The series is endlessly violent, the characters and their back-stories thoroughly compelling (with the exception of Yuka, perhaps) and the art and music perfectly tuned (especially the opening credits’ reinterpretation of Gutav Klimt).

In short, boys and girls, a must-see.

~

Be sure to read Greatest Unknown Anime – Part 2: Shu and Lala-Ru’s Post-Apocalyptic Adventure.