NORCO Is A Connected Web Of Estrangement

As you approach the end of NORCO, Kay – who you spend most of the game playing as – meets two people who you know, before she does, knew her late mother. She spends much of the game waving off awkward platitudes about grief, and explaining to people in her small hometown that they all knew what her mother was up to more than she does. As you pick through the items and memories in her childhood home, it’s clear that they were distant long before Kay ever physically left.

I also know Catherine was up to more than she does, because I spent time playing as her. I recognize the man in the room as Dallas, and the novelty tie he received as a gift from his grandson. (He tells his grandson not to call him “sir”, but he does anyway.) Catherine confides in Dallas as a perfect stranger, knowing their time together is limited to the strange circumstances that bring them together – but shuts down an old friend who knows more intimate details of her history.

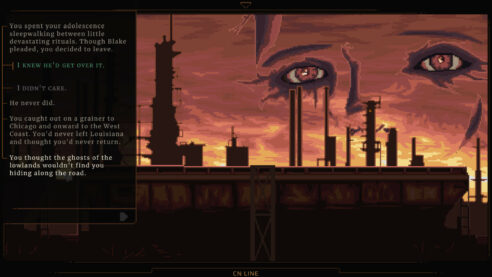

She shares those details with another stranger though – in a clinic, digitally preserving and emulating her memories in a way that she intends to pass them on to her children after her death. She won’t tell them while she’s still alive, even while she’s dying, because their relationship is too fraught to hear it. As you leave the clinic, you can check Catherine’s phone, and read texts between her and both her children. Kay’s are laconic, sending intermittent confirmations of life as she travels and ignoring her mother’s concern. Blake’s are even less flattering, filling in more destructive aspects of his life even before Catherine’s death.

This tension affects every part of NORCO: the desire for connection, and the rejection of it. It shapes the core family in a web, but it plays out across the story’s politics too. There’s a cult made of disillusioned children and teenagers, some of whom believe in their leader’s promise of a new world, but more of whom buy into the promise of inclusion – and opposing exclusion. Fuck you, got mine, and also I’m never doing homework again.

It’s the belief system of people with nothing else to believe in, and no language to recognize what actually suppresses them. They’re united by the concepts of “us” and “not us”, and dissolve into factions about anything that comes after. One key member can defect at a crucial moment if confronted with only the smallest piece of evidence that his father loves him, and still wants him to come home. Catherine collects this evidence before she died, in a conversation with that father about estranged children, and her daughter is the one to deliver it.

When, as Kay, I saw Dallas again, a terrible videogame convention compelled me. I tried to show him one of Catherine’s items, in the hope of triggering some realization between the two. I knew him, even if Kay didn’t, and I wanted the catharsis of reconciliation. Nothing happened, of course: the moment that Kay realizes that he and the other person there knew her mother is only internalized. When the two say “a professor” was fired, it ticks a little update to her mind map about how “mom” was fired. I was the one seeking that connection with a character I recognized, but it was consistent of Kay to refuse it.

Ruth Cassidy is a writer and self-described velcro cyborg whose DMs are open for pictures of mountains & your cats. Direct them to twitter @velcrocyborg