Pentimenti: A Review of Chicory

Well, technically you can make a Marxist reading of anything I said on one of our pandemic walks. It’s like a normal walk, but there’s a pandemic and it’s probably after midnight because Animal Crossing just came out to wreck your newly schedule-less circadian rhythm and what is time even? There aren’t any sidewalks that feel particularly safe by your apartment just off campus either, but you don’t get out much these days so now you’re walking up the buildings overkill, seven story parking garage. The top three floors are almost always empty, though the view of the city some miles away is nice up here. But you probably shouldn’t, I follow up. Not every critical lense illuminates something particularly interesting about everything. But it’s possible, academically speaking. What’s the point, you’d have to ask?

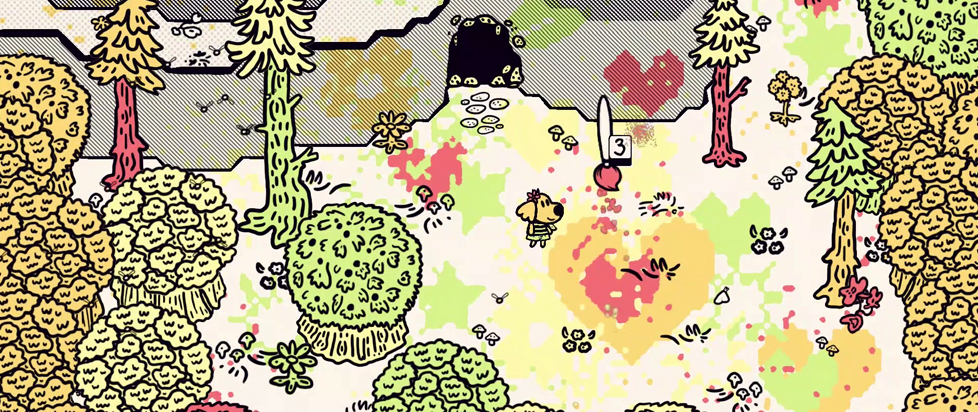

I’ve been playing Chicory: A Colorful Tale, an indie game made by “five friends” not working under any one studio name, during this second pandemic summer. It took me a little over 10 hours to beat, 10 hours that felt substantial the way reading a 300-page book in the same time would. I’ve read a lot of those in the past year, from YA to literary fiction, and in the time melt since I have begun to reconsider that it is not just what we pay attention to that matters, but, to quote an author that has accompanied me through much of this, “maybe what matters most is the kind of attention you pay.” Which is all to say: I know making a book review-length essay and critical reading of a small indie game out of this review may seem bathetic at best, but we’re here now. Infrastructure is crumbling, history is dissolving, and I’ve been playing Chicory.

***

The wood body of my bass guitar is wrapped in a translucent white plastic. Wood grain is visible through the milky texture, and the alder takes on a distinctly lavender hue. It’s a cheap bass. Mass produced, intended for beginners. But as with anything you choose to work with for hundreds of hours a year, its particularities feel unique, existing somewhere between the instrument and myself. The callouses on my fingertips mark me, and I fill in the white body with scratches and discoloration and stickers on the head and pick guard.

In college I had a laptop, and you may have too. You may have also, like me, put stickers on the lid. Everyone at my school did this (it was a big school, anecdotally). Today I put stickers on my record player, my journal, my computer, my amp, my speakers, my bottles, my bike, and sometimes bar bathrooms. Though not in color, each of these are a form of whitespace in the visual landscape of my every day. At cafés and library’s, silver and space gray slates are filled with these details, animating a background with as much extraneous detail as a Shinkai film.

Whitespace is often considered empty space. Minimize it when designing a website, fill the page at least halfway when you print an essay, hang a collage of con art and band posters over bedroom walls. While most everything I’ve stuck, from the transparent cover of the A4 journal I write in, to my blue bicycle, has its purpose, its use, they don’t represent any of my time spent with them…as all of these are made of plastic or aluminum. They record no history. Of course, the belief that whitespace is not in use, and that unused space needs to be filled, is not without its own history. Whiteness is often associated with emptiness: White canvases are blank, white pages are unwritten, white culture does not exist. Though, it would be more accurate to say that whiteness is thought of as default, unaffected, uncolored. Whitespace is the ordinary, and we are trying to fill it in constantly to make something meaningful, purposeful, extraordinary: the canvas with color, the page (this Word doc) with text, and culture with history.

In her poem “An Old Woman,” Mina Loy writes, “The past has come apart/events are vagueing/the future is a seedless pod/the present pain.” The present comes last, caught between a history coming undone and a future that cannot take shape. We exist in an interim influenced by products of pasts removed from their contexts and contradictory desires for futures as history folds in on itself.[1] In sticking everything, I see a desperate want for discernable histories on the surfaces of our lives. A struggle to delineate individuality from an immutable world becomes as a contemporary anxiety, and in want of history our art emerges as pentimenti.

In Chicory the world is already full, inhabited by animals, communities, nature. Color was not always there but has been for so long that no one has seen the world without it, but color is still not ordinary. Instead, it represents that which is simultaneously ubiquitous and phenomenal. It is understood as a component of the world that introduces something to the experience of people’s lives, whether it’s a graffiti mural or a rooftop view of the sky. Color is not purely additive.

With its themes of creative expression and burnout, color in Chicory is an artistic panacea, but color must be made. In this land called Picnic, one animal wields “the brush” to color in the world, a power that is passed down from wielder to wielder. Their onus is to the people of Picnic. They don’t have any power over them, but none are left in want either. The wielder gives the world its color because over time, and with rain, it fades. Each successive wielder, then, colors the world anew, and their job never ends. The blank screens of the game are not unused, not simply whitespace, but non and player characters want to see them in polychrome.

The weight that rests on wielders, the effects of burnout and depression on creative expression, artistic output become the focus of Chicory as the unalienated, communal setting of Picnic, where capitalism is a fringe ideology and only color is scarce establishes a ceteris paribus for this thematic exploration.[2]

The brush is currently possessed by a rabbit named Chicory, and the player character, a dog I named Oreo, is their janitor. Oreo idolizes her artistic ability, reveres the sole responsibility that comes with the station. Like many they want to become the next wielder, but those others are mostly at an art academy, training. The catalyst of its story, and the justification for the mechanical conceit of the game, is that some blight has set on Picnic and erased all its color. The wielder is nowhere to be found, and her janitor picks up the brush to live out their own fantasy. They quickly stumble into Chicory’s shirked responsibilities and take over with a need to prove themselves.

Oreo comes to understand Chicory’s struggles with a great familiarity, recognizing her pain in the other surviving wielders. “When you become a wielder, you aren’t drawing for yourself anymore,” a lion named Cardamom remembers. The common thread among the burnt-out artists is of course the brush, and Chicory and Oreo come to a head in debating its purpose. Chicory argues “if it’s hurting us, we should question why it’s here,” while Oreo’s aspirations keep them dedicated to a future with color.

This leads me to resist some of the words that are in close reach when approaching a game positioned as Chicory has been. Yes, it’s adorable when Oreo recognizes a non-player character and they wordlessly bounce up and down with excitement. It’s charming how every area of Picnic is named after different meals, and characters are named after their regional courses. It’s delicately saccharine as I stop at one of the game’s many phone booths for advice, reach out to Oreo’s mom (also a dog) and tell her about their day. She always says she’s worried about them, makes a comment about how they always end up in these situations. Then the grubby hand of a trash panda reaches for the phone. Dad (a racoon) who wants to tell them lovingly exactly what to do, but only if they want to hear it. But this is all in service to a world that is coherent beyond aesthetics. Cute does not grip below the surface, wholesome does not unravel the compounding, ambivalent emotions Chicory raises.

It’s remarked upon by the curator of Picnic’s art museum that past wielders artwork lacks the color they were made with. Color in our world can fade as well, such as happened to classical marble statuary and renaissance painting alike. And as in our world too these are then colored in by the contemporary wielder. Color constantly changing isn’t exactly fantastical, but it is a dynamism that cities, suburbs, and certain architecture diminish. The wielders position in Picnic then, is a great fulfillment of arts ability to transform the world. As if unencumbered by alienation that detaches us, conservatism that maintains status quo, whole cities can be reimagined.

But it’s not just for a lack of preservation that we make new art. While mediums like music only exists as a sonic sensation when its being played (on a stage or a vinyl), we make new music too. Because like color in Chicory, art undoes the world, constructs it anew. Learning is integral to this deconstruction. As a game, Chicory teaches you to paint. New mechanics are carefully added, and reasons for creating are doled out to you. The slow crawl toward a more complete freedom of expression helps players, like any artist in training, translate their vision into reality by becoming acquainted and comfortable with each part of the process. Learning how to make art does, more immediately however, break down other art. To know how the symphony is written, how the paper is inked, how the clay is spun, these do not diminish such works, but build them up. From pointillism to shoegaze, art itself can even seek to uncover this process.

As we come to see the world through creating art, art also accompanies our reorientation. Characteristics of Lena Raine’s soundtrack are present: delicate drops of a piano suspended on strings, walls of synth crashing down in rhythmic waves. But inspirational city themes reminisce the jubilant piano of Kanako Hara while a wide instrumentation of woodwinds fit seamlessly into accompaniment with strings and piano evoke Joe Hisaishi’s poignant nostalgia, and boss fights incorporate orchestral rock by way of jdk. None of this sounds derivate, to be clear. These additions feel a natural progression in her discography. Raine’s distinct composition colors the diverse soundscape of Picnic in an entire palette of her own creation. And so, the space I have filled in is but one experience of Picnic, one of infinite representations.

This experience, an orientation to the possibilities of the world around us, is wonder. Sara Ahmed writes that “To see the world as if for the first time is to notice that which is there, is made, has arrived, or is extraordinary. Wonder is about learning to see the world as something that does not have to be, and as something that came to be, over time, and with work.” So, Oreo resists Chicory’s monochromatic proposition. Color in Picnic constantly transforms the world, revealing new ways of looking. In its whimsy, this can reveal puzzle answers, script, and layers of graffiti abut butt jokes. And in the game’s most intimate moment, Oreo and Chicory paint portraits of the other, coming undone by their gaze. In sharing their vision, each wielder begins to think of, to see themselves differently.[1]

At the end of Chicory, Picnic arrives at an altered state of creation. In Oreo’s steps, the ability to color, to create becomes a possibility for all of Picnic’s residents. “Color is free,” as the rabbit puts it. The world remains as mutable and dynamic as before, but the potential for change that color offers is more fully realized. The ability to make the world as we might want to see it, to map its surfaces, can now be made in the images of others. Color in Picnic materializes a promise of art that has often felt unfulfilled in our own, that it can by itself undo the world. Stickers, graffiti, and other art that fill the nonplaces of the end of history can make us see the world differently, can build up an alternate reality, but not undo what is present, never make another. In Picnic as on Earth, the canvas is never blank.

[1] I ship it.

[1] Entertainment can function, or be made into a frame, an outline, a context for the disaffected. One that gives shape to life and work while leaving a space for derivative creation within.

[2] I like this setting as a sort of escapist fiction, but the game notably disregards the primary drives of burn out and mental illness among artists in our own world.

[3] I ship it.

———

Autumn Wright is an essayist. They do criticism on games and other media. Find their latest writing at @TheAutumnWright.