Maybe The Last Of Us Part II Was Trying To Frustrate Us?

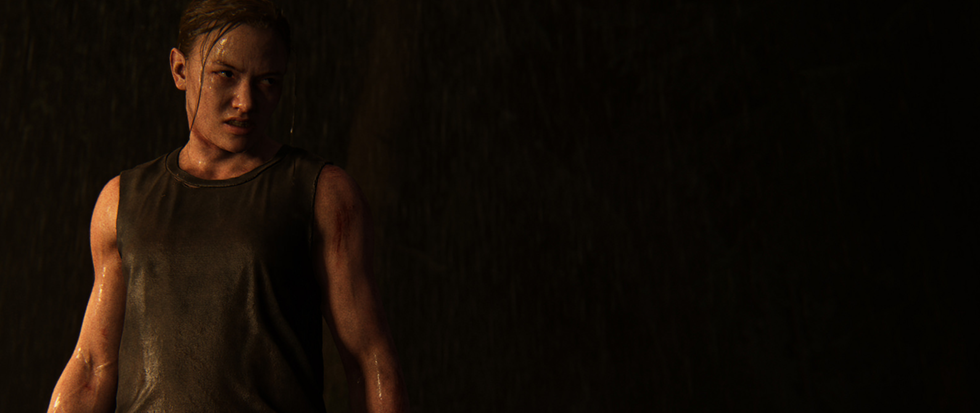

Midway through Naughty Dog’s blockbuster The Last of Us Part II, the game takes an abrupt – and, to some critics, frustrating – turn. Previously a story about Ellie, a battle-hardened woman in search of vengeance for the death of a close friend, the narrative suddenly launches us into the perspective of the Washington Liberation Front, the same enemy we have spent the past four hours tracking, bludgeoning and brutally killing. Through WLF Leader Abby Anderson’s eyes, we grow to see the group as composed of human beings who have deep relationships and moral motivations. It’s a disorienting choice by creative director Neil Druckmann that left many players asking: Why?

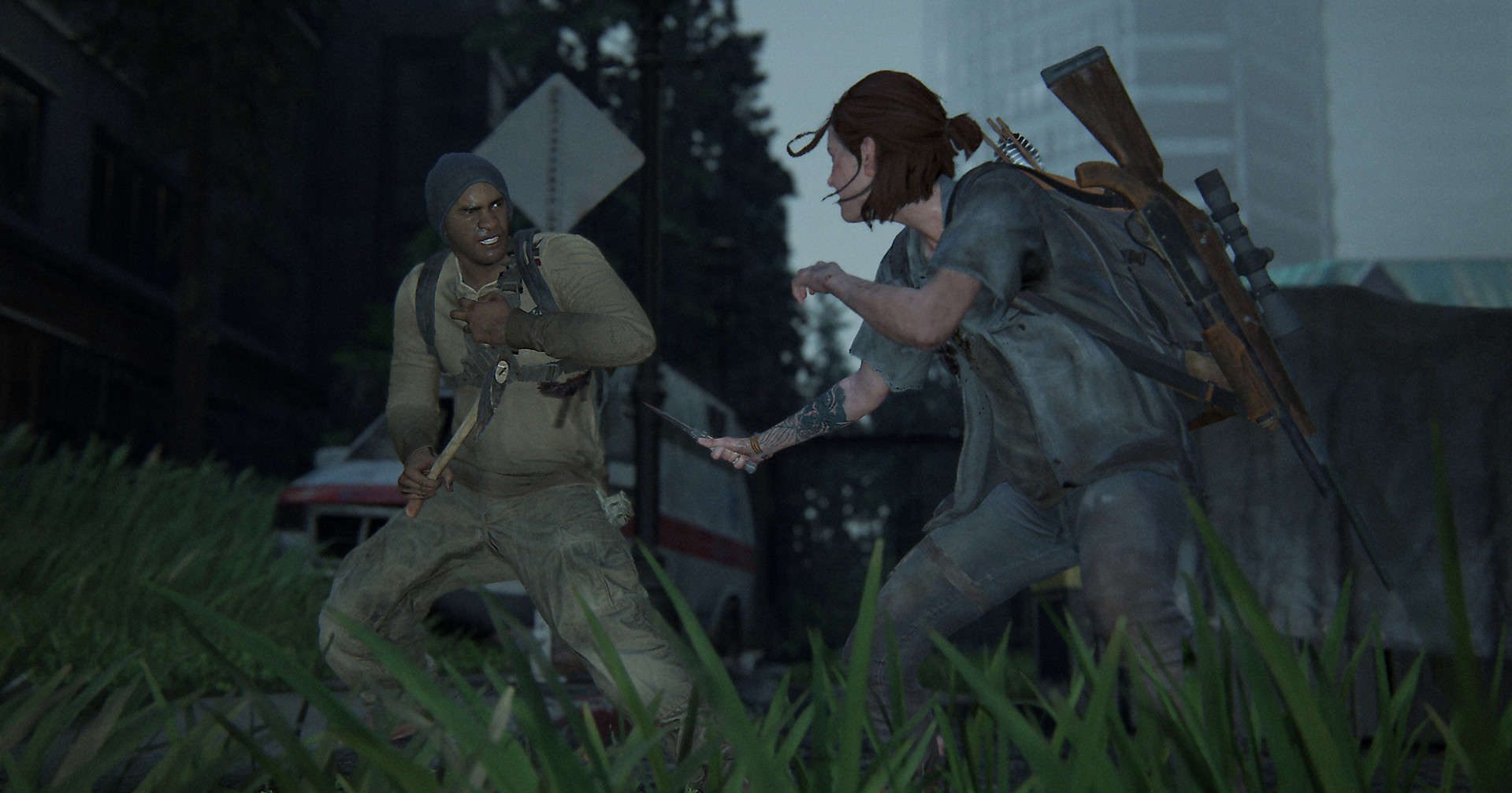

Initially, what might trouble someone about TLoU II‘s narrative twist is how it repeats a gaming trope that you might call a “complicity trap.” Common in critically-acclaimed titles like Bioshock or Hotline Miami, the complicity trap involves a title’s attempt to deconstruct gaming’s bloodier tropes, often through a climactic twist that forces us to gasp in horror at our complicity in past brutal in-game actions. It begs us to ask, “Why have I been blindly following instructions to kill these digital characters? Am I… a monster?”

Frustration sets in when we consider that none of these games – TLoU II included – ever gave us another option. After all, there was no “Pacifism Mode” to make our characters come out of hiding, hug their enemies, and declare world peace. The developer created the game, you think in annoyance. Why did they design it this way if they didn’t want me to kill? It feels like an easy nod towards a stickier problem, one that raises a thorny question about violence without any real answers.

But what if there was a game that decided to use the frustration from the complicity trap mechanic in a deeply intentional way? What if their game’s entire point was to make use that sense of cognitive dissonance to ask questions about our own habits?

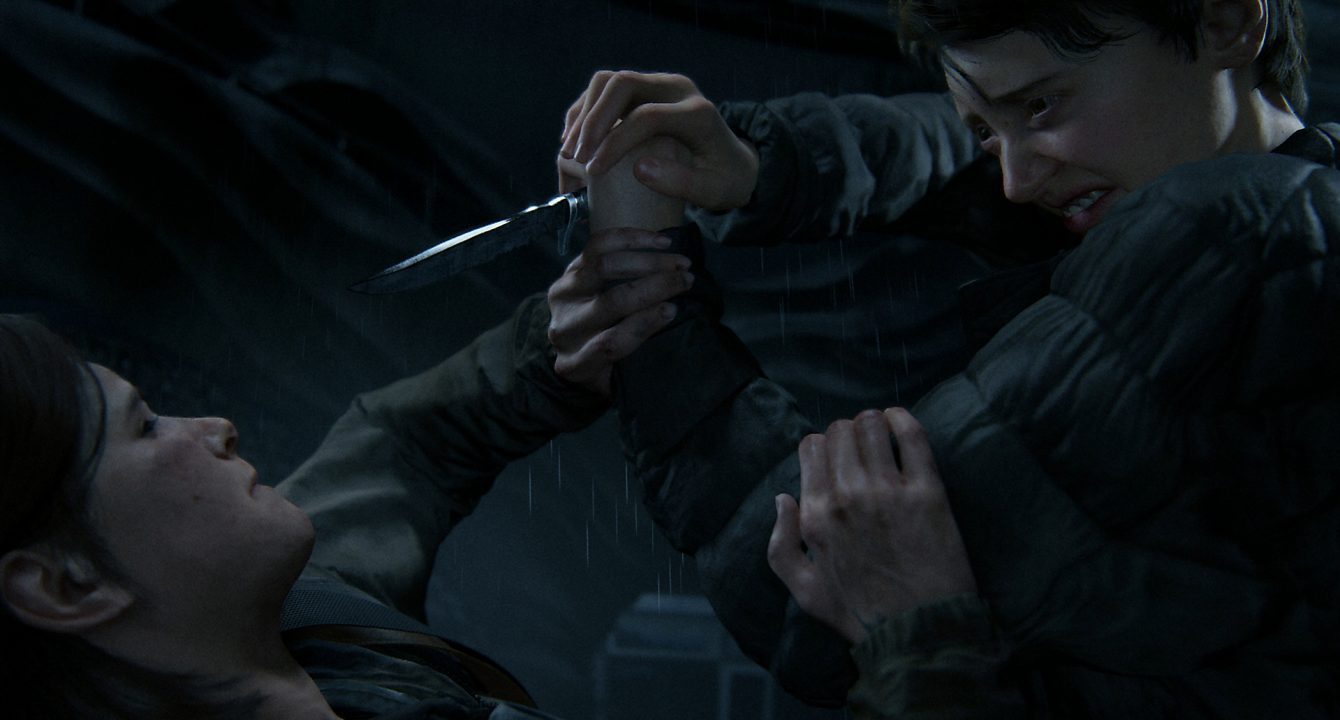

I think those are the motivations behind The Last of Us Part II‘s narrative twist, and especially its climax, where we jump back into Ellie’s perspective fully aware of Abby’s depth as a human being, and yet still resume our campaign of bloody revenge. Again, that irritation arises: Why am I doing this? I get that these people have deep romantic lives and adorable dogs. Let me stop bashing their heads in.

But if we linger on that frustration for a moment, I think it’s worthwhile to consider what it might mean for a writer like Neil Druckmann – who has noted the game was partially inspired by his childhood in the West Bank – to intentionally instill this feeling in gamers. Why would someone want to force us to consider the experience of knowing an action is wrong and yet perpetrating it, again and again? Is it possible the game simply wants us to feel – deeply feel – how so many individuals like Ellie and Abby are locked into a sort of cosmic automaticity in their need to blame the other, to ignore injustices, to forget their own complicity?

It’s easy to wave this away as a simple lesson to learn, and yet it’s clearly a lesson so few of us truly incorporate into our lives. Call it habit or biological nature or kismet, but it’s difficult to deny that we all often operate within our own preconditioned historical experience, rarely erring from the norms handed down to us, rarely questioning why exactly we choose to behave in one way over another.

This, I believe, is what the game is interested in teaching us. The player has no agency over the murders in the game because Ellie herself has little agency over the cycles of violence and injustice into which she’s been born, because we are all, to some extent, stuck in this same rut, and because overcoming these ingrained patterns of hatred is so damn difficult.

It begs the question of whether developers might skillfully use such mechanics to force a player to confront similar dissonances in their own lives, whether the gaming industry could become less interested in making a player mindlessly collect tokens to purchase a new skin or follow arrows toward yet another rat-killing sidequest, and more fascinated with how to awaken us to become better people.

All of this nods towards the Buddhist idea of karma, not in its pop culture conception of “what goes around comes around,” but as the idea of culturally- or biologically-conditioned behavior from which we’re all trying to awaken. Seen this way, the bulk of The Last of Us Part II‘s game-time is supposed to be the frustrating nightmare of history, in which automatically performed prejudice and oppression dominates. The game’s final moments, in which Ellie, in a flash of mercy, gives up on her mission of vengeance and allows Abby to flee for freedom, are a hopeful and hard-earned awakening.

The goal – simple, but wildly difficult – is that more people open their eyes.