A Most Horrific Man

The earliest memory I have of The Fog is catching it during one of those monster movie marathons channels used to run on weekends in October, the ancestors of Joe Bob Briggs’ MosterVision. I was at my grandparent’s house down the shore and expecting the usual fare of kaiju or schlocky 50s B-movie monsters. What I got, though…

One scene in particular stands out: when the young boy Andy walks along the windswept beach and finds a piece of driftwood emblazoned with the name of the ship that is haunting Antonio Bay. I didn’t get much farther than that – soon after, the wood spontaneously combusts while a ghostly voice recites a verse from “Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” all of which was far too frightening for me at that age. That didn’t stop me from scouring the local beaches for similar flotsam, though. I still have plenty of salt-soaked lumber in my basement to prove it.

The man behind the camera of The Fog (and a good number of my nightmares that weekend) was, of course, John Carpenter, one the great (if not greatest) directors of modern horror.

Carpenter was born in 1948 in New York but grew up in Bowling Green, Kentucky, where his father taught music at Western Kentucky University. By most accounts, Howard Hawks’ The Thing from Another World (1951) did to Carpenter what Carpenter’s The Fog did to me. Instead of hiding under the sheets, though, he started on the path to becoming a filmmaker attending Western Kentucky University, then University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts. He dropped out to make his first feature, the short film The Resurrection of Broncho Billy (1970), which won an Academy Award for Best Short Subject.

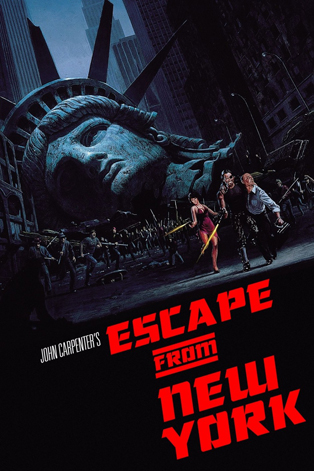

Carpenter’s early career is populated with (now) well-regarded classics like Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), The Fog (1980) and The Thing (1982). While most were well received by critics, only Halloween (1978) and Escape from New York (1981) made significant returns at the box office. Carpenter’s middle period from 1983 to 1995 is, with the exception of Starman (1984) marked by a turn toward less marketable subject matter (1987’s bizarre Prince of Darkness and 1988’s subversive satire They Live, for example) and a steady decline in financial success.

Carpenter’s early career is populated with (now) well-regarded classics like Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), The Fog (1980) and The Thing (1982). While most were well received by critics, only Halloween (1978) and Escape from New York (1981) made significant returns at the box office. Carpenter’s middle period from 1983 to 1995 is, with the exception of Starman (1984) marked by a turn toward less marketable subject matter (1987’s bizarre Prince of Darkness and 1988’s subversive satire They Live, for example) and a steady decline in financial success.

The abominable Escape from L.A. (1996) marked the start of short but precipitous decline in quality that ended when Carpenter entered semi-retirement in 2001, after the release of Ghosts of Mars. He emerged briefly three times in years since – twice to film short installments for the Masters of Horror series, “Cigarette Burns” (2005) and “Pro-Life” (2006) and once to direct The Ward (2010).

As I’ve grown older, the esteem I held for most of my early heroes in the horror genre has shrank. This isn’t down to quality, but rather because I am constantly discovering new voices and there is only so much esteem to go around. The lone exception to this is John Carpenter. While I have always enjoyed a large number of his films, I find that his truly great ones somehow get better with every viewing. And where, when I was in high school, he was largely considered a hack or a cult director, his larger influence has grown exponentially in recent years. You can see his mark left on the makers of dozens of recent, noteworthy horror movies and thrillers like The House of the Devil, Cold in July, The Purge and Blue Ruin.

Carpenter is unusual in other ways, too. Unlike other influential horror directors of his generation, like Wes Craven and Tobe Hooper, Carpenter’s filmography includes an equal number of non-horror films. Assault on Precinct 13 is a siege thriller, Big Trouble in Little China is probably the best example of a decidedly 80s strain of action/adventure movies while They Live and Starman established his cred in science fiction (the latter even netted Jeff Bridges an Oscar nomination). And then there is Escape from New York, the dystopian, near-future action movie that stands in a category all its own. Few other horror directors have shown such range.

Carpenter is unusual in other ways, too. Unlike other influential horror directors of his generation, like Wes Craven and Tobe Hooper, Carpenter’s filmography includes an equal number of non-horror films. Assault on Precinct 13 is a siege thriller, Big Trouble in Little China is probably the best example of a decidedly 80s strain of action/adventure movies while They Live and Starman established his cred in science fiction (the latter even netted Jeff Bridges an Oscar nomination). And then there is Escape from New York, the dystopian, near-future action movie that stands in a category all its own. Few other horror directors have shown such range.

Deep veins of paranoia and isolation unite Carpenter’s entire body of work – even the bad movies, and boy, are there some stinkers. These are powerful tools for a filmmaker. They make a bright sunny day menacing and turn a friend into a foe. More importantly, they stay fresh for decades. Movies that represent anxieties over stranger danger and communism are still just as potent thirty years later because they tap a deeper current that runs under the surface of our lives. Just turn on the TV and watch the news – how many segments look like they were directed by Carpenter?

Even the most terrifying and alien of Carpenter’s creatures wears a human form (except that stupid car). In those dark silhouettes, you can trace the shape of our darkest fears.

———

Every October, I wind up watching a good number of John Carpenter’s horror movies as a matter of course, but this year, I’ve decided to watch all of them, in chronological order, and use that as an impetus to finally write down all my thoughts about them. I have a lot of Carpenter thoughts.

The playlist:

The Thing

Christine

Prince of Darkness

In the Mouth of Madness

Village of the Damned

Vampires

Ghosts of Mars

The Ward

After much thought, I’ve decided to not include They Live, partly because it strikes me as more of a science fiction action movie that is scary in parts rather than a formal horror film, partly because I wrote everything I had to say about it last year. The same can be said of Assault on Precinct 13 as a thriller. If time allows, I will also take on Body Bags, Cigarette Burns and Pro-Life, and tackle Carpenter’s influential soundtrack work.

I have some fellow travelers on this journey, too. My girlfriend, Daisy DeCoster, who is not even a casual horror fan, has graciously volunteered her projector to screen the Carpenter movies. The only Carpenter film she has seen is In the Mouth of Madness, but she’s seen it more times than she can count thanks to an ex-boyfriend only owning five VHS tapes. My pal and fellow horror hound Shawn Dillon will be tagging along for Carpenter’s later movies to see if our earlier judgments of them being unwatchable garbage need revising. Expect to see both their comments in short appendixes to the essays.

———

Follow Stu Horvath on Twitter @StuHorvath