This is Not Your World: An Essay in Two Parts

I.

I’ve been reading a lot of critic Susan Sontag’s early essays of late. I’ve been motivated by a desire to have my own approach to criticism influenced more by that of other critics, and I’ve been influenced heavily in the way Sontag takes a work of art at face value. Explicit in her essays from the late ’60s, “Against Interpretation” and “On Style,” and implicit in the rest of her writing, is this refusal to separate an artwork’s “form” from its “content.” That is, she refuses to separate an artwork into what it “is” (a canvas, brushstrokes, colors, frame), and what it is “about” (love, happiness, sadness, passion, war, whatever). She makes a point of not talking about artworks like they are “containers” full of some meaning. Instead, she works to flatten art: what an artwork “means” and what it “is” are not different things; an artwork is not a glass container to be filled with “content.” She forwards a way of talking about works of art as they are, talking about how the “content” of a work of art isn’t beyond its formal elements, but emerges from those formal elements.

[pullquote]It is up to the player to build the fourth wall, to create that separation of the virtual world from the actual world, […] to feel immersed.[/pullquote]

Of course, she goes into a lot more detail than that, but that is the gist of it. It has had me thinking these past months about the parallels between form/content and how game critics and players often talk about “immersion, ” how we wish to have an immediate experience of the “content” of a videogame’s virtual world while we don’t want to have to think about its formal elements (controllers, discs, wires, batteries, USB ports, television screens). “Immersion” has already been extensively critiqued as a term (most fruitfully by Richard Lemarchand in a GDC 2012 presentation and in Ben Abraham’s response, both arguing for a discussion of “attention” instead of “immersion”). Just like “form” and “content,” we could not feel immersion without those physical, formal elements we try not to think about. Without a controller in our lap or a television screen before us or, perhaps, an Oculus Rift strapped to our face, we could not pretend we are immersed (and make no mistake, to be immersed is to pretend, to make believe). Virtual worlds only exist in the coming together of very non-virtual elements of videogame play.

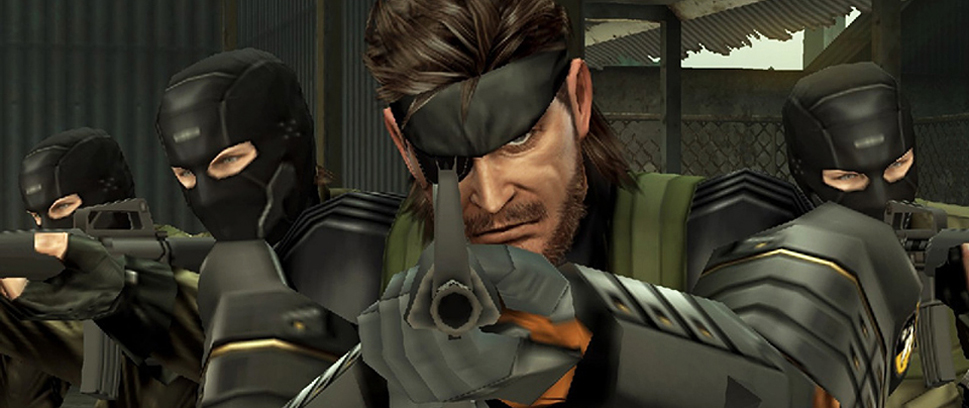

This has led to a renewed interest in me of those videogames that acknowledge that videogame play is always a clash of form and content, of actual and virtual elements. It has renewed my interest, for instance, in the Metal Gear Solid games and their regular breaking of the fourth wall. The way a character, without a hint of irony, will tell the player/Solid Snake to press the “action button” if they want to climb a ladder. The way Otacon will marvel about Blu-ray technology in Metal Gear Solid 4 that allows the entire game to fit on a single disc. The way the players’ tandem to the virtual world – the controller in their hands – is both their greatest weakness and their greatest strength against Psycho Mantis in Metal Gear Solid.

Hideo Kojima is not just adding occasional, novel, fourth-wall breaking moments just for the heck of it. Rather, he is unashamedly making videogames that do not pretend they are not videogames. Videogames that do not separate “form” and “content” but that are quite aware how entangled the two are on such a mundane level. Solid Snake doesn’t blink when he is told to press the action button – this is a videogame; of course that is how he climbs a ladder.

So the game critic, if they are to understand what a videogame is doing, needs to understand this clashing of the actual world with the virtual. The best critics already do this, of course, effortlessly combining the buttons they are pressing with the actions of the character in the same sentence. The lure of immersion, however, constantly tempts us to talk about virtual worlds as purely virtual worlds, detached from the “real” world rather than a dependent part of that real world. As players, we want to feel immersion. We want to make virtual worlds make sense independent of the actual world.

So the game critic, if they are to understand what a videogame is doing, needs to understand this clashing of the actual world with the virtual. The best critics already do this, of course, effortlessly combining the buttons they are pressing with the actions of the character in the same sentence. The lure of immersion, however, constantly tempts us to talk about virtual worlds as purely virtual worlds, detached from the “real” world rather than a dependent part of that real world. As players, we want to feel immersion. We want to make virtual worlds make sense independent of the actual world.

An example drawing upon a piece of writing that has disappeared from the Internet (well, mostly): Tim Rogers essay on Earthbound. There is an anecdote some way into this essay where Rogers discusses a dilapidated house missing the rear wall. Rogers doesn’t discuss this house as a house with three walls, but as a house with two walls: the third wall has collapsed, and the fourth wall has been removed so the player can see into the house. This is a common trope in JRPGs and 2D games generally, but we never really think about it: entire walls are removed so the player can get a clear view. In those screens, that wall simply does not exist. We, as players, imagine it into existence. It is up to the player to build the fourth wall, to create that separation of the virtual world from the actual world, to separate the game’s content from the form, to feel immersed.

To put it another way: virtual worlds are myths. Kieron Gillen says as much in his manifesto for New Games Journalism when he notes that we are writing about places that simply do not exist.

———

II.

This week, I began playing Media Molecule’s new game Tearaway on the PlayStation Vita, and I am convinced this game was made just for me. It is a game that directly confronts the fact that its virtual world is a myth, and that our interactions with it are always across the divide of worlds.

One of the first things the narrators say to the player in Tearaway is, “This is not your world.”

It’s a bold way to start a game. While almost any other game tries to help the player imagine the virtual world as sealed off, as a world they are entirely embodied and present in, Tearaway explicitly wants the player to know that the world on the screen is not their world. The narrators continue to tell the player that this is a “world of stories” as they bring things to existence with their words. This is a temporal world that exists solely for the sake of having a story and a game to move through.

It’s a bold way to start a game. While almost any other game tries to help the player imagine the virtual world as sealed off, as a world they are entirely embodied and present in, Tearaway explicitly wants the player to know that the world on the screen is not their world. The narrators continue to tell the player that this is a “world of stories” as they bring things to existence with their words. This is a temporal world that exists solely for the sake of having a story and a game to move through.

Once it is made clear that the virtual world is not “your world,” the presence of your actual world in relation to the virtual world on the screen is made clear. The rear camera of the PlayStation Vita shows the actual world around you on the screen, before a hole rips open and spreads, turning the screen into a viewpoint on the virtual world (as all screens are, really). Moments later, through the Vita’s rear touchscreen, you are poking your fingers into the virtual world to move objects around. Paper tears open as virtual depictions of your fingers jut out into the virtual world; in the small gaps around the fingers, you can see glimmers of the actual world beyond the tears. Your fingers become your agents in the virtual world: the way you are able to affect things in this virtual world that is not your own with an actual body (as fingers do in all games, really).

Tearaway comments explicitly on the interrelatedness of actual and virtual worlds that immersion tends to obscure, and it does so in the most delightful and effortless ways. In some ways, it plays like a release title for a new platform, like a game that primarily exists to demonstrate what a piece of hardware can do. Indeed, it is the exemplary PlayStation Vita title, so much so that already I have trouble imagining one without the existence of the other. It brings together the device’s cameras, touchscreens and buttons to maintain a focus on the blurry, electric place two worlds overlap. It takes the language of Augmented Reality and flips it: less interested in showing virtual objects in the real world than in showing real objects in the virtual world.

Media Molecule have always made games with a very ‘tactile’ aesthetic. LittleBigPlanet, with its sponges and wooden blocks and knitted avatars was less about the wonders of a fantastical virtual worlds and more about the spectacle of these things working together in a certain way. It was the spectacle of, “How did they make this world?” Like opening up an elaborate pop-up book and marveling at the craft of it. With its beautiful and charming papercraft aesthetic, Tearaway continues this tradition, and it fits perfectly the games broader concern with flattening form and content. Like Kojima’s, Media Molecule’s games do not pretend they are not videogames. They are elaborate stage shows, put on for the player’s sake, as that player literally looks down on the story from their god-like position in the sun.

Media Molecule have always made games with a very ‘tactile’ aesthetic. LittleBigPlanet, with its sponges and wooden blocks and knitted avatars was less about the wonders of a fantastical virtual worlds and more about the spectacle of these things working together in a certain way. It was the spectacle of, “How did they make this world?” Like opening up an elaborate pop-up book and marveling at the craft of it. With its beautiful and charming papercraft aesthetic, Tearaway continues this tradition, and it fits perfectly the games broader concern with flattening form and content. Like Kojima’s, Media Molecule’s games do not pretend they are not videogames. They are elaborate stage shows, put on for the player’s sake, as that player literally looks down on the story from their god-like position in the sun.

Which is not to simply say that Tearaway is a videogame “about videogames” or anything so reductive. But it is a videogame clearly made by people who know exactly how videogames work: how players engage with them through form and content to have a pleasurable engagement. It is a videogame that does not only understand this, but which distills it, distills everything down to this pure pleasure of engaging with a videogame, of being able to touch a world that is not your own, of poking your fingers into the middle of a myth.