Gone But Not Forgotten

I still remember the exact date the videogame arcade in my hometown closed for good: January 28, 1996.

I remember it not because of some elephantine memory or a Good Will Hunting-esque ability to recall specific dates from my past, but because it was the day of the thirtieth Super Bowl. A group of friends and I had some time to kill before the big game, so we headed down to Jackie’s Place, the arcade that had been a fixture in my hometown since the late 1970s, longer than any of us had been born.

[pullquote]Scrawled on that sign in magic marker were three words that sent shockwaves through our bodies. BUSINESS CLOSED PERMANENTLY.[/pullquote]

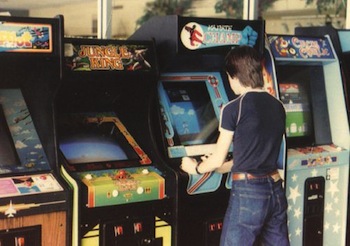

Jackie’s Place was your typical early ‘90s arcade, probably not much different from the arcade in your own hometown. It was 1,000 square feet or so, about half the size of a regulation tennis court, and it was crammed wall-to-wall with hulking arcade cabinets. Dim lighting and dark carpeting masked the stains from thousands of soda cups that had been upturned and pizza slices that had been dropped throughout the arcade’s history. The various sound effects blasting from the games provided the arcade’s background music – a warbled cacophony of bleeps and blips and explosions and synthesized voices. If you listened closely, a lone sound effect could be discerned over this overwhelming typhoon of noise: Ryu yelling “Hadoken” from the Street Fighter II cabinet, the commentator screaming “He’s on fire” or “Boomshakalaka” from NBA Jam, the thundering hum of the engines roaring from the speakers on the quad-cab Daytona unit.

And the smell of the place – I think my nasal passages suffered permanent damage from the overwhelming stench of overbuttered popcorn and body odor and burnt pizza that permeated the arcade.

There are a lot of adjectives that could describe Jackie’s Place – rowdy, grimy, boisterous. Calling it a shithole wouldn’t be inaccurate. No matter – my friends and I positively loved the arcade.

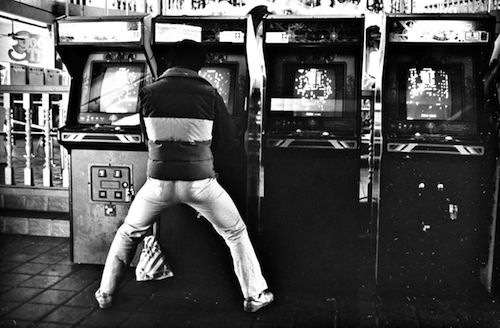

In 1980s and into the early 1990s, arcades were the social epicenter of most teenagers’ lives. They weren’t just a place to hang out; they were the place to hang out. Much like soda fountains, drive-in diners, and skating rinks in decades prior, the local videogame arcade was the place you went if you had a few hours to kill.

In 1980s and into the early 1990s, arcades were the social epicenter of most teenagers’ lives. They weren’t just a place to hang out; they were the place to hang out. Much like soda fountains, drive-in diners, and skating rinks in decades prior, the local videogame arcade was the place you went if you had a few hours to kill.

Sometimes you went with a group of friends. Sometimes you went alone. For many, a trip to the local arcade was ingrained into their daily schedule: you went to school, then to arcade for a few hours, then home to eat dinner and do homework. Rinse, lather, repeat. And you maintained that schedule damn near every single day.

Why did teenagers gravitate towards arcades in that era? For starters, there wasn’t much else to do. There was no internet. Cable television didn’t catch on until the mid-to-late-‘80s, and even when it did start to become popular, there were only 20-30 channels to choose from. There were home videogame consoles to play, but there was a clear distinction between home videogames and arcade videogames –the arcade boards were light years more advanced.

And arcades were fun – that’s the real reason they were so popular. If you weren’t around when the arcade scene was in full swing, you have no idea how much fun you missed. Spending few hours there was an absolute blast, a guaranteed good time. If you had a pocketful of quarters and your best buds by your side, it was impossible not to have fun at an arcade.

An afternoon of fun was precisely what my friends and I were looking for when we parked our bikes outside of Jackie’s Place on that day in January 1996. Instead, we found something that stopped us in our tracks.

All of the lights inside Jackie’s Place were off, and the parking lot in front of the arcade was completely empty. A lone cardboard sign was taped to the arcade’s entrance. Scrawled on that sign in magic marker were three words that sent shockwaves through our bodies. BUSINESS CLOSED PERMANENTLY, it said.

We stood on the sidewalk and silently stared at the sign for a long, long time. At first, we were confused. Jackie’s Place…closed? For good? As the stark reality of the situation sunk in, our confusion gave way to disbelief. It seemed unfathomable that our beloved arcade could close its doors.

We walked over to one of the windows and cupped our hands against the glass to look inside. What we saw hammered home the harsh reality like a twenty-pound sledgehammer.

We walked over to one of the windows and cupped our hands against the glass to look inside. What we saw hammered home the harsh reality like a twenty-pound sledgehammer.

Jackie’s Place had been gutted, completely emptied out. The walls were stripped bare of the game posters and promotional one-sheets that usually adorned them. Every one of the arcade’s cabinets was gone. The NBA Jam Tournament Edition machine that we’d played on for practically every day of the previous summer. The Mortal Kombat 3 cabinet that we’d huddle around in hopes of catching a fatality. The whole collection of early ‘80s games in the back. Even the change machine – the very change machine we’d inserted hundreds upon hundreds of dollar bills into over the years, then heard the satisfying jingle of four quarters clambering down the coin return slot – everything was gone.

My friends and I stood outside Jackie’s Place, in disbelief, for a long time. We were positively crushed, utterly shellshocked, and all of the standard clichés rang true – it was like the death of a family member, the loss of a close friend.

We looked in at the empty shell of our beloved hangout, and I halfway expected a lone tumbleweed to lazily blow across the deserted arcade floor. We tried to make sense of what was going on. But mostly, we focused on that lone sign on the door. Closed for business.

———

I recently wrote a coming of age novel set against the backdrop of the rise and fall of the arcade industry and did a lot of reading up on the arcade business as research. Many articles talked of how sudden the collapse of the industry in the mid-‘90s was, how there were thousands of arcades like Jackie’s Place that closed their doors within the span of little more than a year. In fact, “collapse” probably isn’t even the right word to use when talking about what happened to the arcade industry in the mid-‘90s. It was more like an implosion – a vanishing act, really.

One moment, the industry was alive and well. Then, the original PlayStation was released and the graphical superiority that arcades had always held over the home consoles was gone: Sony’s console had an array of graphically-perfect ports of popular arcade games, and some exclusive titles had graphics more advanced than any arcade game at the time. That had never happened before – in the past, home consoles just weren’t powerful enough to produce games on par graphically with the arcades.

Throw in the fact that the costs of manufacturing a CD were less than a dollar (versus hundreds of dollars to manufacture an arcade cabinet, not to mention the freight costs of transporting 300-plus pound cabinets across country), and the supply of quality arcade games dried up as arcade pioneers like Capcom, Midway, and Komani all either ceased arcade game production entirely or reduced their output to a game or two per year. With few new games being released, arcades dropped like flies. And just like that, the entire industry was gone for good, never to return.

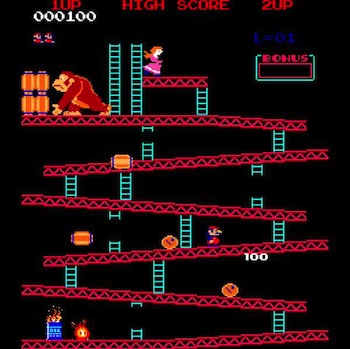

Another topic that many of the articles focus on was the sheer size of the industry at its peak. There were two golden ages for arcade games. The first occurred in the early ‘80s when Pac-Man, Donkey Kong and countless other classics were released, and the second occurred in the early ‘90s with the fighting and racing game boom. I was around for the latter but not the former, and it was startling to read just how gigantic the industry was during its fist, true golden age. It was nothing short of a juggernaut, the biggest entertainment industry in the world by a wide, wide margin.

Another topic that many of the articles focus on was the sheer size of the industry at its peak. There were two golden ages for arcade games. The first occurred in the early ‘80s when Pac-Man, Donkey Kong and countless other classics were released, and the second occurred in the early ‘90s with the fighting and racing game boom. I was around for the latter but not the former, and it was startling to read just how gigantic the industry was during its fist, true golden age. It was nothing short of a juggernaut, the biggest entertainment industry in the world by a wide, wide margin.

Consider these numbers:

In 1982, the arcade industry generated $8 billion in quarters (that’s $19 billion adjusted for inflation), making it the biggest entertainment industry in the world. The second-biggest business was the music industry, with total sales of $4 billion in 1982, and in third place was the movie industry – bolstered by the runaway success of E.T., the movie industry did $3 billion in 1982.

At $8 billion in revenue, the arcade industry in 1982 was bigger than the music and movie industries combined. And that $8 billion figure doesn’t include the money generated by sales of home consoles and games. That’s just revenue generated by arcade games alone.

In fact, in 1982 there were 13,000 videogame arcades in the U.S. To put the enormity of that number in perspective, in 2013 there are 4,000 Wal-Marts in the US, 6,000 Taco Bells and 12,000 Starbucks.

And the neat thing about that 13,000 figure is that, in those days, there wasn’t a large, monolithic corporation that controlled the arcade scene. Time Out Arcade and Aladdin’s Castle were the two biggies, but each had no more than 400 locations apiece.

Instead, most arcades were small, mom-and-pop operations much like Jackie’s Place, and there’s something endearing about the notion that a majority of arcades were small business owned by independent operators squeezing out a living. Arcades weren’t cookie cutter replicas of one another, spread across the nation. Instead, every arcade had its own layout and own selection of games, its own quirks and idiosyncrasies that distinguished it from other arcades and made it special.

It started, really, with the arcade version of Pac-Man, which was released in 1980 and remained a popular draw for a few years afterward. In that time, it generated over $3.5 billion in quarters (8.4 billion in 2013 dollars).

No other entertainment product has ever come within a mile of that figure. The bestselling games for home consoles have generated a fraction of $3.5 billion. Avatar, the most successful movie of all-time, did $1 billion at the box office (and tickets to the movie were in the $10-15 range, a far cry from the $0.25 it cost to play Pac-Man). Michael Jackson’s Thriller, the most successful album of all-time, sold 65 million copies – in terms of revenue generated, it’s not even in the same ballpark as the arcade version of Pac-Man.

$3.5 billion dollars. That’s bigger than a lot of well-known companies. That’s more than many entire industries gross. And $3.5 billion dollars is a whole lot of quarters.

———

Over the past few years, an increasing number of bars with large collections of arcade games have opened up across the US. These barcades have proved to be very popular, most likely due to the nostalgia factor – nostalgia is a very powerful emotion, and it’s impossible to walk into a current-day barcade, see the arcade games that formed so many memories as a kid and not be infected with waves of it. Even if most vintage games can be played from the comfort of your home (or in many cases, right on your phone), there’s something special about playing the game on an arcade cabinet.

But as fun as the current-day barcades are, they’re just not the same. What made the arcade scene so great back in the day was that you never knew what to expect after walking through the entrance. There could always be a surprise in store. Maybe someone would set a high score in a game (a big, big deal back then). Maybe a group would organize an impromptu tournament in a fighting game and you’d jump on the arcade’s phone to call around to as many friends to get them to come down to the arcade to participate.

But as fun as the current-day barcades are, they’re just not the same. What made the arcade scene so great back in the day was that you never knew what to expect after walking through the entrance. There could always be a surprise in store. Maybe someone would set a high score in a game (a big, big deal back then). Maybe a group would organize an impromptu tournament in a fighting game and you’d jump on the arcade’s phone to call around to as many friends to get them to come down to the arcade to participate.

Or maybe there’d be a new game at the arcade. It was an event whenever a new game arrived, an incredibly exciting moment. With no internet and few mainstream gaming magazines, you were often completely unaware of a game’s existence until your local arcade got it in stock. And it was always an adventure when a new game arrived and everyone huddled around the game, eager to try it out for the first time and render their verdict.

But the games were only half of what made arcades special. The kinship and sense of community that developed between the regulars was the real draw. If you were a teenager in that era, you came of age within the walls of your local videogame arcade. You made some of your greatest friends at the arcade, and experienced some of your greatest memories with those friends at the arcade.

Arcades were true icons of the late-20th century. The industry experienced highs and lows during its two-decade run, yet arcades ruled the entertainment landscape for nearly that entire stretch. They exploded onto the scene in the final years of the 1970s and went supernova in the early 1980s, and the industry’s disappearance at the tail end of the ‘90s was equally as quick. In little more than a blink of an eye, the games faded, arcades fell from their lofty perch and the industry was gone for good.

Gone, of course, but never forgotten.

———

Follow Andy Hunt on Twitter @huntand or check out his novel, The Final Day at Westfield Arcade, on Amazon.