Talking is Harmful

One of the best things about GDC is the chats you have with people – with other writers, with players, with developers. One of the worst things about GDC is losing those chats to the ether the moment they are over. I was really looking forward to talking to Walt Williams, the lead writer on 2K and Yager’s Spec Ops: The Line. Mostly, I just wanted to know how he felt about the book I wrote about the game he wrote. And, as it turned out, he wanted to talk to me. So after he gave his GDC presentation on how to build characters through violence, we sat down in a quiet corner of Moscone West and had a chat. We had a chat for over an hour that slipped and slid from one topic into another and back again, from Spec Ops to videogames to writing to criticism.

As I stopped my iPhone’s recorder app and we went our separate ways, I tried to think about how I could condense that chat and all the interesting things that were said during it into a cohesive, linear feature. I realized I probably couldn’t. So, instead, with the few exceptional places where Walt realized he had said something he probably should not have said, here is my entire chat with Walt Williams. Because why not?

———

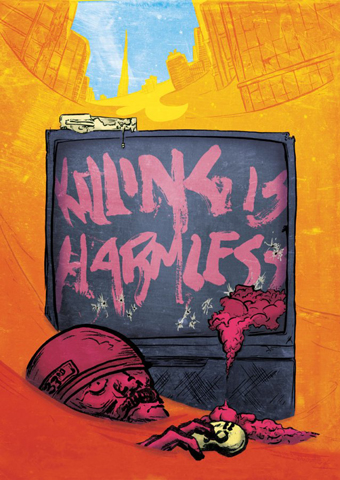

Brendan Keogh: So I wanted to talk to you since, as a game critic, I’m really interested in the tension that is usually there between critics and developers. A lot of the time developers seem to hate us critics and half the time critics don’t seem to know what they are saying anyway. So I was interested in talking to you about Killing is Harmless, about what it was like as a developer to read someone write about your game. And I was wondering what Yager’s thoughts on it were as well.

Walt Williams: That’s cool. I will say, though that I don’t know what Yager’s thoughts on it are.

B.K.: Someone in Germany spent $50 on it.

W.W.: Really? Well now I feel like I didn’t pay enough.

B.K.: So you’re not part of Yager so much as, what, a contractor?

W.W.: No, actually, I’m a 2K employee, and I always have been. And we, it was a weird situation where I developed the original concept of the game along with Yager. 2K loaned me out – I mean, I was already spending like half my time in Berlin working on the game, but towards the end I officially moved over there for the duration of finishing it up.

It’s a very weird position that I have at 2K. There’s three of us – it’s me, Chad Rocco, and Jack Scalici – both of whom also worked on Spec Ops as well on the writing team – where we have to walk this strange line between being publisher and developer because we are essentially creative resources that are loaned to a developer when they need them.

B.K.: Does that give you more freedom to do more risky things? Like, it is pretty surprising that Spec Ops even exists.

W.W.: It does, to an extent. I try to give the people on the team the freedom to do what they want to do. Because the way I see it, writing and design is my forte. If you’re a level designer, well, I’m going to tell you, “Look, this is what the level needs to be, or at least what it has to accomplish. You’re the expert, so accomplish that in the way that you feel it is best accomplished.” And then when they’re done you take a step back and tweak here and tweak there and now it fits with this other piece and boom, we’re done.

So I like to have everyone do what they feel like and not kind of ‘micro-manage.’

B.K.: But do you still keep to keep a kind of creative direction over the work? So many AAA games struggle to have a ‘voice’ since there are so many people working on them. You normally expect it to be the indie games or personal games that try to say something. I often find myself comparing Spec Ops to Bastion because that game felt like it was saying something, like the art and the music and everything was working towards that something, and I get a similar sense from Spec Ops.

W.W.: Well, it’s worth noting that Greg Kasavin [Writer on Bastion] was a producer on Spec Ops.

B.K.: Huh. I think I knew that but then forgot again, so that is surprising all over again!

W.W.: But yes, what’s interesting with what you were saying about vision is that the things with videogames, more than any other medium, is that it is very hard to find the artist within the art. Having known Greg and worked with Greg, when I finally got to play Bastion, I was playing it and I could see Greg in it. I could see his inspirations and how the things he loves about games shone through. I could literally see him within the game. That was the coolest thing for me! And I think it is the saddest thing that it is so hard for us to do that in games. I think we have a tendency to not design from the heart but to design for the audience, so we lose a lot of the artist. But Greg puts a lot of himself into his work.

B.K.: That’s really interesting that I kept making that connection between Spec Ops and Bastion without knowing that. But what about you. How did you get into working on games?

B.K.: That’s really interesting that I kept making that connection between Spec Ops and Bastion without knowing that. But what about you. How did you get into working on games?

W.W.: Well I’ve been working at 2K for 8 years, believe it or not. It is the only job I’ve ever had in the games industry. I moved up to New York [from Louisiana] when I was about 23, 24 because I wanted to be a comic book writer. My girlfriend at the time was moving to New York for grad school and I was like, fuck, I’m not doing anything else, I’ll go. New York sounds cool. I fell in love with it instantly. So I met a guy in a bar in New York who went to the same college as me and had lived with two editors-in-chief of this satirical newspaper I wrote for during college. He was like, “So what do you do?” And I was like ,“I don’t do anything right now, man. I have no job.” And he said, “Well I’m the hiring manager at Take Two, so why don’t you send me your resume?”

So there was this production assistant job – we called them game analysts, back in the day. So I came on doing this production assistant job and I thought, okay, I’ll do this until my writing career takes off. But then it kind of became my writing career. Like, they knew I could write; they knew I had a background in it. I understood script and structure and all that stuff, and that’s what they needed for the projects they had on the table at the time. I think one of them was the Family Guy game. My boss came into work one day and he was like, “I’m going to send you to Chicago to go help this game out because I think this is your kind of humour.” It was a weird moment because I thought to myself, “Well, getting fucked up and watching Family Guy for four years of college actually turned out to me a really great educational move!”

But I had literally been in the industry for three months and they were sending me out to a developer to rework level design and that sort of stuff. And the thing is, with videogames, I think we don’t like to think about how much of it connects to film, and the concept of how film is made. But it is very similar, and not in a bad way.

B.K.: I know! I get so angry when people complain about ‘cinematic’ games. I’m like, “Videogames are cinematic!”

W.W.: They’re totally cinematic! Like, a good camera placement is a good camera placement. A good cut is a good cut. Good dialog is good dialog. We get afraid that we following movies but the thing is, it is about composition of a visual and audible medium, which is what we are, and there are definitely things we can learn from that.

But I think subtlety is a very hard thing to pull off in games. That is something I noticed with Spec Ops. A lot of people said we were a bit on the nose. And, to be fair, there are a lot of things that are on the nose in Spec Ops, but nobody actually picked up on the things in there that were subtle. For instance, no one picked up that Konrad being dead when you find him, of a gunshot wound, mirrored the exact same choice that Walker is then given. And if Walker is the player, then Konrad is the designer. Because a lot of people were like, “It is completely ignoring the designer’s role in making this world!” No, actually the designer just put a bullet in his head before you have the same choice, because this is the designer saying, “Yeah, we totally just made this horrible shit. Like, this is what we made and it is really fucked” and that was the choice I made when I put a bullet in my head. And no one got that.

So I don’t know if maybe subtlety is hard to pull off in games because maybe we don’t expect it? I think, when dealing with Spec Ops, mixing both being on the nose and being subtle, doesn’t necessarily make you want to look for the subtle parts. That might’ve had something to do with it. All this said, I blame myself entirely for all the shortcomings in the game.

B.K.: So what is your history with shooters? Do you enjoy playing them?

W.W.: I mean, I grew up playing them a little bit more. I played Doom II with the mods and I played Counter Strike Source and had LAN parties.

B.K.: Less so the more modern shooters?

W.W.: Well, yeah, this was very back-in-the-day. Honestly, I’ve always been more of an RPG guy. I like RPGs. I also loved the Jak and Daxter series. Anytime one of those came out I would skip college for three days and just play it. But whenever a new Final Fantasy came out, you never knew where they were going to take you. There was always this wonderful sense of discovery. I didn’t care if there was definitely going to be chocobos and mogs and black wizards. There was going to be a whole new world and you were going to get to uncover it. It was going to be completely different from the previous one. I loved that sense of discover. That’s what really drew me to that. And I think it is something the genre has lost, that sense of discovery.

B.K.: Did that funnel back into Spec Ops somehow?

W.W.: It did. There are actually a few things I did in Spec Ops that I learned from Final Fantasy. Like simply not telling the player things, leaving things unanswered for the player to figure out on their own. Because when I was a kid, in Final Fantasy VI, there’s a character called Shadow, he can join your party. He’s a ninja. Have you played VI?

B.K.: Um. Only the first bit. It is on the top of my list of shame.

B.K.: Um. Only the first bit. It is on the top of my list of shame.

W.W.: Okay. This is a slight spoiler but the game never actually reveals it to you. Okay, so then there is this little girl called Relm who lives with her grandmother, and she has her mother’s ring. It’s a relic that only she can wear. The thing is, Shadow can also wear it. And every now and then if you sleep with both Shadow and Relm in your party Shadow would have a dream, there would be this dream sequence. Eventually it was him with his dog, but before he put on the ninja thing, in a town, and he is leaving a women behind. And the dog always reacts to Relm. And I was like, “Oh my god. He’s her father!” And I tried all these things to make them realize it. I even wrote a letter to Nintendo Power! That was such an amazing thing to me that within a game I could figure something out that was obviously intended but was never explicitly told to me. As a kid I thought that was amazing.

So that is really what I tried to do with the intel items in the game. There’s a letter from Konrad to his son, or the poem that Konrad wrote to his wife. Just small things like that that allow you to find out a little bit more about who these people are. Things that didn’t necessarily fall into the way you are presenting them. Like, just the idea that Konrad would even write poetry. That this is a man who has a softness to him, and he has had to kill that to do what we thought he had to save people.

B.K.: I guess the difference is that in Final Fantasy you often get to encyclopaedically know that world eventually. But in Spec Ops it is always hidden behind multiple layers of illusion and subjectivity.

W.W.: That’s true. Actually, a good friend of mine from school who is a psychologist now played the game recently. I’d never thought about what a psychologist would think about playing the game. I think it is interesting that you find these intel that are talking about Konrad and they actually all directly mirror Walker’s psychosis, not Konrad’s. And my friend is telling me the psychological words for it and I was like, “I didn’t even know there was a thing for it but, yes, that is it!” Because when you find Riggs and the psychological report of Konrad, it was meant to mirror Walker at that point, but I didn’t realize how much all of the other Konrad things were, from a psychological professional standpoint, mirroring Walker. So it was really cool to have someone who does that for a living draw these lines. Because I think with writing, especially in games, so much of it is up to the beholder as they play it. There are a lot of wonderful things that we put into our games that we never actually intended to do. Because you have a rhythm of flow to your writing. Sometimes you simply understand something and you’re like, “Yes, this works.” But you might not understand why; you just get the sense that it does. Then someone else reads it and they’re like, “Oh this works because of this.” And you think, “Oh! Yes! I guess that does work!”

B.K.: I guess that is why artistic intentionality is never the entire story when it comes to a work.

W.W.: Yeah. It is a weird thing.

B.K.: I want to come back to that in a second, but firstly, you mentioned in your lecture just before that you have family members in the military. Would you say you’re from a military family?

W.W.: It is a military family! Both grandfathers, my father, my brother, my uncles, myself briefly.

B.K.: What were you?

W.W.: Oh I was bad, is what I was. They kicked me out. I had potential and I didn’t live up to it.

B.K.: Did any of that influence Spec Ops in some way?

W.W.: It did, actually. The thing is, I still have quite a few friends in the army – well a lot of them are out now, to be honest, but when Spec Ops was first starting many of my friends were still in the military. And my brother was spending time in Iraq. He did two or three tours over there. He is a civil engineer, and they’re the people they go after! And like, you’d get emails from him that would say, “You’re going to hear about an attack on the Green Zone. Everything is fine. Wasn’t anywhere near me.” But then I’d get an email just to myself that’s like, “It hit my parking spot five minutes before I got to work. Don’t tell dad.”

And knowing people who would go over and do this for a living, and do it because they believe in it, and looking at how some of them come back just a little different. Not even noticeably. Just, like, you are talking to them and turn to someone else and you come back and you can see they are somewhere else in their head. You don’t know what they’re thinking about, and you don’t know why but they just are somewhere else. Just seeing that and seeing how we treat military games it just…it just seemed wrong.

B.K.: Is it something about how all of them, especially Medal of Honor I guess, try to claim authenticity. Is there something offensive about that?

W.W.: It is offensive. Because, first off, why the fuck would you want to create an authentic combat experience? Like, it’s the ‘Glory of War’ concept that I thought we had put to rest. But war… war is not fun. War is scary. War is frightening. I mean, it’s very easy to just sit on your couch and just play a game and feel like, yeah, I’m being a badass. But Jesus. I’m not comfortable with guns. I’ve fired a gun maybe four or five times in my life. My entire family owns guns. And, actually, I totally support the freedom to own guns, it is just a freedom I choose not to exercise. I just don’t think we understand truly what it feels like to be in a situation where we might die. And that we are not being very aware how conflict over there is going when you make a game like Modern Warfare or Medal of Honor. I mean, yes, sometimes conflict is like that for these top tier soldiers. Most of the time it is not. Even then it is not… fun.

B.K.: It misses what happens to the person.

B.K.: It misses what happens to the person.

W.W.: It does, and that is what I wanted out of Spec Ops: that this stuff affects people. It affects the person that is committing the act, because it is. I had a friend out of high school that was a cop. All he ever wanted to be was a cop. He loved it. Then one night, he had to shoot a man while in the line of duty. He saved people’s lives that night by killing that one person. The guy tried to kill him. He was defending himself when he shot that guy. But it was still so impactful to him that he just left the force and never went back. He just couldn’t reconcile that he had killed a man. This is a man who specifically wanted nothing but to be a cop.

Then there is a moment when I was in the military during the summer training. One of those pilots who fly those gunships in the Call of Duty missions where it is night time and you have the camera. One of those pilots showed this video at an assembly. You could hear the pilots joking about the people they were killing. Like, they were leading a guy. They were leading a guy. With bullets. And the guy was hiding under a truck and they were waiting for this guy to come out and they killed him. And this room full of people, they were laughing! And, like, no one… it crossed no one’s mind that you were watching actual footage of people being killed. It was just so off to me. Like, I got that they were combatants. I got that they were out enemies in a conflict. I wasn’t thinking “This is just wrong”. I was thinking “The way we are reacting to this is wrong”. I get that there are people you sometimes have to kill, but it’s not funny. There’s nothing funny about this. And leading a guy? If you have to kill someone then, well maybe it is just my Southernly Gentleman coming through, but you just kill him. You get it over with. You don’t fucking toy with the guy.

So these two things came up into my mind when I got into writing a military shooter. Also, admittedly, with Spec Ops, there was a very long period of time where Konrad was still alive and the story was very simple. We didn’t have the white phosphorous. Walker wasn’t crazy. But every step along the way we were like, “Wow, Walker is not a very likeable guy, and the decisions he is making are not very likeable. He seems kind of crazy.” And my immediate response was, “Well, yeah, everyone when you play a fucking shooter is crazy because nothing you do in a shooter is logical.”

B.K.: So you were brought onto a game that was already a military shooter, right?

W.W.: Yeah, we always knew it had to be a military shooter.

B.K.: And so maybe you just ended up making the kind of shooter you were inevitably going to make?

W.W.: Yeah, actually. We always knew it was going to be a military shooter, and we always knew it was going to be Spec Ops, and there was even a time where I was fighting to get the ‘Spec Ops’ part dropped as I always felt the military part was the least important part of the game, and if we were going to make a franchise out of the game I would want it to continue not as a military game but continue more about the hard decisions we have to make in life.

So, yeah, it just kind of ultimately… I think a journalist tweeted something as people were reviewing the game along the lines of, “Wow. Someone working on this game really doesn’t like the player.” And I’m just like, “You figured that out, huh?” Because there was this point where the pain of the product began to show itself within the project. It reached this point where it was like, “Oh, you want to play this kind of game for fun? Fuck you, I’ll show you what’s fun about this.” And it just started to turn. But once we started to analyze that emotion we were like, well, actually, there is something here. There is something to this that is very real and which should be said.

And that is an interesting thing with talking about game production. We don’t like to admit that the game we ship was a different game at some other point in time. Obviously Spec Ops ended up with a message and a very particular point of view but it wasn’t always like that. It was like six completely other games before it got to that one! Because that is the creative process! Especially in games. Something new clicks in your head and you think, wait, we’re onto something different! Not this, but we’re very close to this thing that is even better! So all of the emotions and everything eventually came to a head, and a lot of the game is very personal.

B.K.: It almost sounds like you approached it like an actual writer.

W.W.: Yeah, that’s true! The thing with writing games is you have to be comfortable with throwing your words out. I genuinely feel that if someone plays Spec Ops and they just don’t get the story at all, but if the entire experience guided them to feel the emotional beats that I wanted them to feel, that at the end of the game they have ended up at the same emotional place, then I don’t give a shit what story they got out of it. Because ultimately the story, or writing in general, you just take a bunch of fucking random lines that mean nothing and you put them in a certain order to manipulate the emotions of whoever views them. It’s all about the emotional reaction. That is what you are trying to get, and I think that sometimes as writers we forget that. We think our words are the most important thing but we are putting our words together to create a certain emotion, to guide the viewer into a certain area. So in a videogame you’ve got two different narratives: the one I write and the one you got going on in your head. I couldn’t tell you what the story was in half the Final Fantasy games I played was, as I was making up my own, but I still ended up doing what they wanted me to do. So it’s something I think it is important for a games writer to be comfortable with: letting your story be the least important thing. I see it as writing with emotions.

B.K.: So there’s a lot more to being a games writer than just the story.

W.W.: Absolutely! Like they say, kill your darlings.

B.K.: Does that seem to be something that videogames are just figure out? Like, it has been a few years now that people have been saying that, yeah, writing matters! And now maybe we are finally starting to see the fruits of that push?

W.W.: Well, I think it is that there are finally enough writers working in the industry now who have been around long enough to understand design. I think that is the key. For so many years we’ve had designers who thought they were writers writing games – and some of them certainly are great writers! Ken Levine is designer who is a great writer. Tim Schafer is designer who is a great writer. But now there are so many writers who know how to think about design. Because you do have to think about writing differently in games, and that is what is fun about it, to be honest. Especially because there is so much ground we haven’t covered yet, narratively.

And that is what I would say is really cool about Spec Ops. We were making it and we thought, “Nobody has every really done this. Nobody has said this in a shooter before. Nobody has ever said, ‘What if shooting is kind of fucked up?’” That’s cool that we can say that! There are so many things that we haven’t said yet, as a medium. Even more so I think we are the only medium that genuinely has the ability to create new experiences and worlds and places to inhabit. It’s not voyeuristic. We can create actual, genuine experiences for people to go through. But we are stuck on this loop of… basically, we are gods. We can create worlds. And all we are doing is recreating the harsh world that we live in. And the truth is our time is limited. Like, this is our one opportunity to make whatever we want and we are really, really comfortable just remaking our childhoods. That’s scary to me.

B.K.: So what do you do next then?

W.W.: Do you mean me personally?

B.K.: Well. I think my question was meant to be that once you critique shooters and say that, yeah, they are fucked up, then what do you do?

W.W.: I want to make a AAA game that is as action-packed as a game like Bioshock Infinite or Spec Ops or Uncharted where you play someone who doesn’t kill people. Or doesn’t punch people until they just conveniently vanish. I want to play a pacifist in a world that is trying to kill me and I want to come up with new ways of dealing with conflict resolution. And I want to do it in a way that is as action-packed as a summer blockbuster. I think it is possible.

B.K.: Okay, so let’s actually talk about criticism. So I’m really interested in the relationship between critics and creators. And I’m really interested in the form of videogame criticism. I think, really, it is probably fair to say that I am more interested in videogame criticism than I am in videogames. That is my thing. So I’m really interested in what it is like for creators to read criticism about their work. What’s that like? Is it weird?

W.W.: I think it is different for everyone. I would say that as the game was getting ready to come out—

B.K.: Actually! I should ask: have you read Killing is Harmless?

B.K.: Actually! I should ask: have you read Killing is Harmless?

W.W.: I have read… bits of it. I have not read the whole thing.

B.K.: In hindsight, that is an important question for me to ask!

W.W.: It is! I haven’t, and when I knew you were going to be here I thought I should really try to read the whole thing but it is really hard to read it knowing that this is a book about something I wrote. It’s daunting. It’s very daunting!

B.K.: I feel terrible just assuming you had read it!

W.W.: Nonono. I feel bad. The thing is, I bought it the moment it came out and printed it out immediately. But it has been hard to read Killing is Harmless because I never ever expected that someone would write such an in-depth criticism of it. It is one thing to interact with a review, but to interact on a level of critique that is this big, I don’t know how to do that. Like, there was one thing that I saw and I thought, “He’s wrong on this. Do I tell him? I should tell him! No, I shouldn’t tell him! That sounds rude!” And that’s the thing. With the world being so much smaller these days, I don’t know how to interact with you in that regard. That has been what has held me off from reading the whole thing. I don’t know how to digest it.

There was one thing. When you are repelling down at the start of Chapter Nine and you mention you thought that you saw that reflection—

B.K.: Oh no. Is it not actually there? I swear I saw it!

W.W.: No that’s the thing, you were right! And I wasn’t sure if I should tell you that you were right or not. I realized I had no idea how to interact with this thing.

B.K.: I’m so happy I wasn’t imagining it!

W.W.: Yeah. It’s Lugo.

B.K.: I… Wait. What? It’s Lugo?

W.W.: It’s Lugo!

B.K.: I’ve had people tell me I am reading too much into this game – which is still certainly true at points – and their proof is often that I say that there is a ghost there!

W.W.: I know! And I really wanted to tell them, no! He is not reading into it too much! It is totally there! It is Lugo hanging in the window as he is hanging at the end of the game.

B.K.: Shit. Wow.

W.W.: And the other part of it is that one of the things I was really excited about with Spec Ops as it was about to come out is that it was very specifically designed to have a surface story and you just get what Walker is doing. There is that surface story, but there are like two other levels beneath. You didn’t necessarily have to read into it that it was talking about you, the player, playing a shooter. And you didn’t necessarily have to pick up that Walker might actually be dead. You could still totally just enjoy the surface level of the story. And I was excited about people having different interpretations with that. And that’s the other reason I didn’t know how to interact with you about Killing is Harmless is I didn’t know if I should say that anything was definitely right or definitely wrong.

B.K.: See, that’s interesting to me as I don’t think videogame developers have quite tackled the concept of artistic intentionality and that it is problematic, that the creator is not in charge of what a game means once it is out there in the world.

W.W.: It is problematic. And I want to know why we are so frightened of it. We do seem very frightened of intentionality. And, obviously, everyone is frightened of criticism to a certain degree. With Spec Ops, there had to be 20-something drafts of that game, and that hardens your skin pretty quickly. So with actual criticism of it, most of the criticism I’ve read of it is totally valid. I’m certainly aware of a lot of the flaws in the game.

B.K.: Well, I mean criticism more as analysis, not necessarily negative criticism

W.W.: Well that’s a good point. I’m not sure we’re afraid of that kind of criticism so much as we’re just not prepared for it. This is what I think is so awesome with what you did with Killing is Harmless. It basically said, “No, hey guys. Games actually have more here to find than what we’re looking for.” And I think the sad thing is that I don’t know if we on the creators side have provided enough of that for people on the critical side. Off the top of my head I can’t think of too many games that need a deeper reading—at least not on the AAA scene.

B.K.: And I think that is one of the main reasons I wanted to write it. Because I felt like I could, and I never had felt like I could before. I thoroughly enjoy AAA games, and I think they all deserve good criticism, but you can’t help but feel that sometimes you are clutching for a meaning that isn’t there, right? That’s more of a point than a question, I guess.

W.W.: Well, it is a good point! I’ve certainly worked on AAA games where the meaning is “Make it awesome so that people will buy it!” or “Make it funny so people will laugh!” Even the gritty darkness of Spec Ops was originally coming from a place where this is just what people want in their game right now—and that is what eventually led to the “Isn’t this kind of fucked up?” question. But yeah, we do. We make our art based off of what we think the most number of people want.

B.K.: So, this is totally a self-indulgent question, but do you think having a richer critical discourse happening around games maybe allows more games to at least try to mean something?

W.W.: Absolutely. Absolutely. 100%. I think it is absolutely necessary, and I am so fucking glad it is happening now. I’ve been doing this for eight years, and I can’t imagine if in another eight years I am still making the same kind of games.

We want to say we are art, we want to say we are all artists but yet we do everything possible to disprove that by simply churning out games that are FUN and EXCITING and that just fall into a certain paradigm. Having critical discussions allows us to go, hey, actually, what if we’re not just about fun?

And it has to do with what we call ourselves, right? ‘Games’ has a very particular intonation with all these things come with it and I think a lot of playing games does tie in with trying to capture something from when you were younger.

B.K.: I clearly can’t ask you to speak for all AAA developers but do you think others would consider themselves ‘artists’ in a medium worthy of critical attention? Or are they just happy to make Fun Games?

W.W.: I think most of them would, actually. They’re probably not all as critical of the medium as I am. I think it is hard to make something critical of something you love. I don’t feel anything wrong with saying something critical about it. Especially in a game, which I think is the only way to say something appropriately critical about the industry, at least for me.

B.K.: But do you think for most developers, if someone wrote something critical—not necessarily negative—about the thing they made, do you think they would be happy that people were writing about them?

W.W.: I think they would. I think we all think we are making important stuff. It certainly feels important to us while we are making it. There was a very long time for me in this industry before Spec Ops where I just wanted to be the writer who could give the publisher what they wanted. Just tell me what you want out of this thing, I’ll do it. This is a job. I’m a carpenter. Tell me what kind of bookshelf you want and I will build it, and it will be a bookshelf that stands and holds books. And my boss at the time was like, “What I want, is for you to build the bookshelf that you want to build.” I fought that for the longest time but eventually I built the bookshelf I wanted to build and now I have no fucking idea about how to just go back to building bookshelves that someone wants you to build. I think there is a line that you cross where you pour a bit of your own heart out in your work and you realize you have more than you want to say. That doesn’t mean that anything I wrote before didn’t feel as important to me; I was just looking at it more from a service point-of-view, rather than a personal one. So whether we see it as personal or as a service, I think we all think that what we are doing is important. Like, providing a good service is admirable. And it is hard to do. So I think we all see ourselves as artists, even if we are just making Iteration Five of something.

But frankly why I think it is starting to change is that we are all getting older and we are starting to realise that we have been doing this for many years. We have families and kids and we think, “I don’t want my kids playing this.” I think that is happening to a lot of developers as they get older. When you’re younger, think of the movies you liked in college. You just wanted shit that was badass. And games I think are kind of moving into the college phrase where we see a cause and we think, “Yeah! Free Dafur! Now let’s get high and watch that movie where a thousand people get blown up by razor guns!” We’re trying to grow up and be important and say things, but at the same time we’re still really comfortable being children, and being young, and just having fun.

B.K.: Right. I’ve heard people say before that videogames aren’t a young medium so much as they are an adolescent medium.

W.W.: Yes, absolutely! We are totally in the adolescent college age. If we can get games into the early 30s before I leave this industry at the end of my life, I will be very pleased with that. Early 30s is where we need to go. It’s as if your body and your mind just run out of fucks to give. Film has that. Like, we get so up in arms whenever we get attacked. Film just goes, “Fuck you, we’re film.” But we are all, “No! You’re wrong! You’re all wrong! You don’t understand us! Play Journey!” No. Don’t do that. I hate that. Don’t point… we are trying way too hard to validate ourselves as a whole. But like, we all get it, right? We get why people who don’t play games look at us and wonder if we are making people violent. Because we just make things where you kill hundreds of people with no emotional context and it is specifically designed to make you go, “This is awesome!” As an industry, please tell me we get this.

B.K.: But at the same time, it feels that a lot of players, too, are reluctant to think critically about games. You see comments on critical essays all the time saying, “It’s just a game! Stop over thinking it!”

W.W.: Well exactly! That exact same thing comes through in the development process. We don’t look at ourselves critically, and we don’t want to. We just want to do what we are doing and think everything is fine.

B.K.: Maybe that is why it feels to me that there is this tension between developers and critics. To me it feels like whether you write something positive or negative, the developer will often see it and go, “No! That’s not it!”

W.W.: Yeah, I think there is something to that. Like, you do get personal about your work. Me, I don’t care. If someone interprets my thing wrongly or they just don’t like it then that is totally a valid opinion.

B.K.: Have you read many negative pieces about Spec Ops?

W.W.: Some.

B.K.: Do you feel, “No you don’t get it!” or “Okay, I see where you are coming from?”

W.W.: No, I totally see where they are coming from. I mean, if I read a piece of negative criticism on Spec Ops, my usual thought is that I fucked up by not making the point they missed more obvious. It is a totally valid criticism because if they didn’t get the point that I tried to make then they are totally right. That is a learning experience for me. I don’t need to read positive reviews, because my ego doesn’t need that. But the bad reviews are the only way I’m going to learn what I did wrong and learn for the next one.

B.K.: My three favorite reviews of Killing is Harmless – all by guys I know, I should add – were all quite negative, but constructively so. And, well, on one side I felt defensive, like they were just saying “You didn’t give me what I wanted to get out of it” but, at the same time, there were some very valid criticisms in all of them that I’ve taken to heart in my writing. But they were so hard to read. It was so hard to be on that side of the critical process for once.

W.W.: I was getting really nervous as Spec Ops’s release got close because this was the first time I was putting something out there in the critical sphere for people to comment on. That is extremely daunting.

W.W.: I was getting really nervous as Spec Ops’s release got close because this was the first time I was putting something out there in the critical sphere for people to comment on. That is extremely daunting.

But Killing is Harmless was incredibly flattering. That feels really weird to say but it was flattering. Just the idea that anyone would care enough about something you wrote to put that much thought into it… it means that we affected people. That’s ultimately what you want to do. And we thought it would affect people, but we thought it would affect them in an angry way. We didn’t expect people to connect to it in the way that they did, so that was even cool. And also, writing is hard! So the idea that someone that does what I do would sit down and write that much about something I wrote is… wow.

B.K.: But there’s that line that critics can cross where they become sort of armchair developers, and I think a lot of critics are really cautious of doing that. That is bad games criticism, but I think that is what most developers maybe think most criticism is. And maybe it is. I don’t know!

W.W.: I think that is fair. I think there is a bit of that.

B.K.: Do you think maybe it is just a tone thing? Just a framing of how we as critics say something doesn’t work?

W.W.: Right. Some of the dialog in Spec Ops was criticized in one review as being too glib. And maybe it is too glib, but I want to know which dialog, because there is a lot of dialog! And I don’t know if you’re like this but if I look at something I wrote a year ago, I’ll think it is shit. A year ago I thought it was great because over time you just grow as a writer by writing more and more and more. So when I get something like “Dialog is too glib” I at least want to be able to learn from it. Like, if the next thing I write is like Spec Ops, then I’m a failure. If it sounds and reads just like Spec Ops then I’ve failed as a writer in my opinion as it would mean that I’ve learned nothing since Spec Ops. Everything I write, I would have that it has grown from the last thing. If it hasn’t, then why am I filling space that a better writer could be filling?

B.K.: Right. Because I think that is what games criticism can do for developers. Not say, “This is what you should have done” but say, “This is why this part connected to me but that part didn’t”

W.W.: Yeah. And I think that is incredibly helpful. Because we don’t interact with that part of the audience as much. And that is why I love hanging out with journalists and critics so much after the fact. That’s really the closest you are going to get to your playing audience that can articulate a real response to what you made, and you can understand it better through there eyes.

B.K.: I was recently reading Nöel Carroll’s On Criticism as I was trying to figure out what the hell I meant when I called myself a critic, as I felt like I was just using that word recklessly. He says that a critic is an expert audience. Like, someone who is an expert at being an audience for an artwork.

W.W.: Ooh. I like that.

B.K.: And he says something else. I forget the exact words but pretty much, the critic gives the audience the vocabulary for what they already know is in the work. That is what I got out of games criticism before I actually started writing it myself. I would read something and be like, yeah, that is what I felt! These words! Now I can say what it was. And I think that is useful for players, being able to articulate how they felt, but it is also useful to take back to developers.

W.W.: I agree 100%, and as more games are released that are open to that much in-depth criticism and study it is going to become an extremely important thing to have people doing that. Otherwise we are just farting in the wind if there is no one there to say anything about it. We can try to say things with meaning but if you never get any response to that meaning then you don’t know if you are succeeding or failing.

B.K.: You just have a crowd who thinks it is fun.

W.W.: Exactly! And, shit, if that is all we are ever going to get out of it then I can save myself a lot of heartache and just stick to fun and not write meaningful.

———

Follow Brendan Keogh on Twitter @BRKeogh. You can purchase a digital version of his book on Spec Ops: The Line, Killing is Harmless, at Stolen Projects or on Amazon. Photo of Brendan and Walt courtesy of Dennis Scimeca.